It’s a real-life Jurassic Park scenario: for decades, all most people have heard of Erich von Däniken is the occasional fossilized soundbite (such as “Chariots of the Gods“). But now, like a ferocious Tyrannosaurus Rex cloned from dinosaur DNA, von Däniken is back with a new (2009) book called “History Is Wrong” – it lives, it liiiives!

…OK, that’s a bit of an exaggeration. The von Däniken that emerges from its pages is, let’s say, far less bodacious than the one of old – though his most famous subjects of interests (Nazca lines, metal library, Book of Enoch, Father Crespi, etc) all get wheeled out, you don’t have to read too far in to notice that his delivery has changed from ‘strident’ to (frankly) ‘rather whinging’.

Actually, for the most part “History Is Wrong” focuses less on why historians have got ancient history wrong than on why contemporary historians have got von Däniken wrong – to be precise, its full title should be “History Is Wrong… About Me!”

Hence, he goes to some lengths to paint a picture of how (particularly in the case of the underground metal library) his sources switched their stories to make him look like a fool; how subeditors and translators altered the slant of his text to make him look like a showman; how journalists (specifically German ones) serially misrepresented his claims to make him look like a conman; and, finally, how everything he wrote back then still remains basically true today. Even if everyone else thinks it’s nonsense.

So, I think the key question this book poses for the reader is whether history is right about von Däniken – is he (or is he not) a foolish showman/conman?

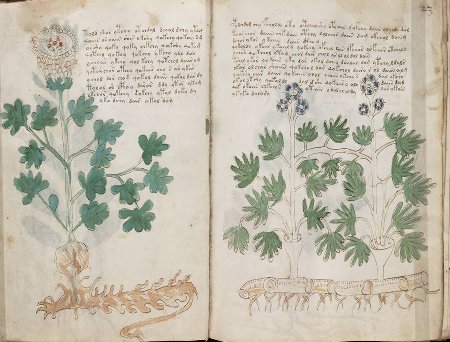

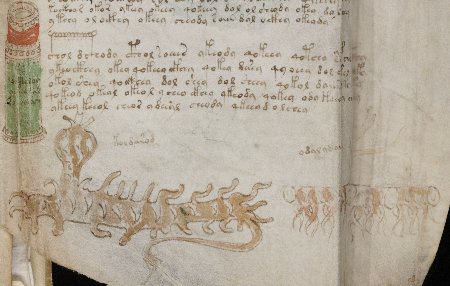

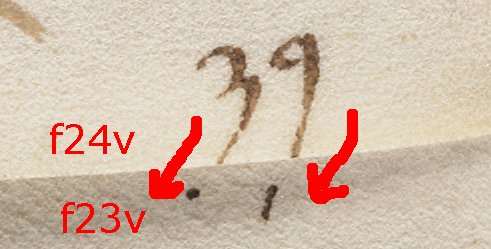

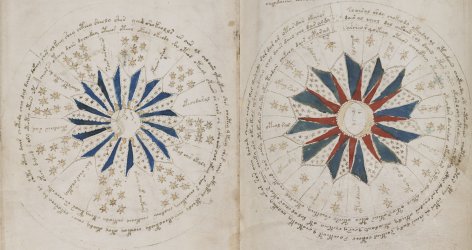

I’ll answer this by looking at how von Däniken looks at the VMs (which is, of course, this blog’s specialist subject). He opens the book by describing how he asked a hundred people if they had heard of the Voynich Manuscript – only one person had (yup, 1% or 2% would be about right). He then quickly recounts its history (getting some bits right, other bits wrong) with a few minor digressions, before leaping sideways on page 21 to Father Crespi, Plato, terraforming, Adam’s book, Berossus’ Babyloniaca, the Avesta, Enoch (for more than 30 pages!), IT = “Information Trickery”, Plato again… until finally (on page 81!) he loops back to the Voynich Manuscript again (but then only very briefly).

From my perspective, I don’t think you can say that von Däniken offers anything useful or insightful about the VMs that hasn’t been rolled out a thousand times before – for example, though he discusses “89” and “4”, he does this in only a fairly superficial way. The only interesting Voynich ‘authority’ EvD cites here is “German linguist Erhard Landsmann” (p.85), who (rather impressively, it has to be said) concludes in his own Voynich paper that “A prophet is thus a pumpkin shaped spacecraft” (p.6). [Note: his name is actually “Landmann”.]

Purely based on EvD’s treatment of the VMs, I can only really conclude that:-

- von Däniken doesn’t read his sources as carefully or as deeply as he thinks he does.

- He actively seeks out fragmentary correlations across time and space, which he then misrepresents as compelling evidence of causal connection between the two.

- He doesn’t really know how to do history: his interest is in peering past mere facts to the shared web of doubt that he believes supports them all, that offers us glimpses of the “gods-as-astronauts” meta-narrative behind historical reality.

In short, his book is no different to the mass of non-working, unmethodical Voynich theories out there already, with the only exception being that he doesn’t even get as far as suggesting an answer. Even for von Däniken, that would be just too whacko a thing to do. 😉

And yet… because his book is in many ways an autobiography, the main thing that emerges from it is actually EvD himself: a charming and driven man, yet a victim in equal parts of his own optimistic enthusiasm and other people’s bullshit. Really, if you had a meal with him circa 2010, I think he would actually be delightful company. Sure, he became madly rich from his books (and goodness knows that few authors manage that these days): but maybe History will indeed turn out to have been (a little, just a little) Wrong About Him – that for all the readers taken in by all his non-history, I suspect that perhaps he conned himself ten times more.