WAGtv’s “Ancient X-Files” Voynich episode will first air at 20:40 on 10th May 2012 on the National Geographic channel in France, where the series has been retitled “De l’ombre à la lumière“. Though the episode is entitled “Sodom and Gomorrah” (“Sodome et Gomorrhe” in French), be reassured that 50% of it is the Voynich part. 🙂

And by a nice coincidence which Nat Geo’s schedulers seem, errrm, mostly unaware of, this is also when I shall be in Frascati preparing for the upcoming Voynich Centenary conference the following day. It’s time to tell some of the story behind the documentary…

1. “The Curse of the Voynich” Meets WAGtv…

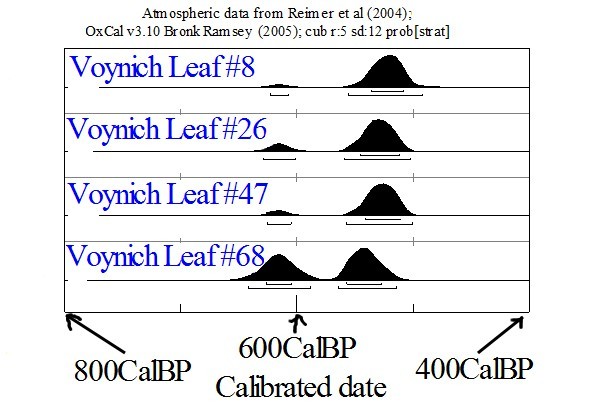

Back in 2006, the general consensus was that the Voynich Manuscript was an extraordinary late 16th century hoax, constructed to part an extraordinary fool (Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II) from his extraordinary money (600 gold ducats). And without the 2009 radiocarbon dating (which dated its vellum to 1404-1438 with 95% confidence) to help ground the whole debate, the Voynich was arguably even more like a blank historical canvas (upon which you can paint whatever theory you like) than it is today. Sad, really.

2006 was also the year that I wrote and published “The Curse of the Voynich” (copies still available, and at very reasonable air mail rates 😀 ), with the aim of summing up the research I had built up over several years – basically, that the Voynich Manuscript may well have been written by Northern Italian Quattrocento architect Antonio Averlino (better known as “Filarete“).

However, put these two things together and it should be no great surprise that, a couple of nicely appreciative reviews aside, my tree of research fell onto the Voynich research community’s forest floor with a deafening silence. (If, indeed, it fell at all.) Personally, I still think my book is a great piece of historical detective work (I posted a nice summary of it here), but I suspect it remains too “out there” for almost all Voynich researchers, most of whom seem to rely more on lightweight inductive logic than on the kind of heavyweight hyper-deduction I had to employ. 🙂

Fast forward to early 2010, when London-based factual television production house WAGtv were working on the the first series of Ancient X Files for National Geographic. Their producers approached me to ask if I would contribute to a 22-minute documentary segment based on “The Curse of the Voynich”: though it just missed the cut for series 1, I was delighted to be able to take part when they subsequently wanted to include it in series 2.

This whole Voynich segment was filmed over five days last summer [2011] in locations centrally linked to Antonio Averlino’s life and works, such as the Ospedale Maggiore & Castello Sforzesco in Milan, and the Campanile in Venice (looking down onto the onion domes of St Mark’s Basilica). Just so you know, the televisual conceit was to visually reconstruct the evidence chain and associated reasoning that led to my whole Averlino theory. In case your inner historian finds this somewhat annoying, please take a few deep breaths and remind yourself that “it’s just television” – if you want to read up on it properly, there is at least a 230-page book you can buy that presents all the evidence in a reasonably compelling way. 😉

2. Meet The Experts…

Naturally, there are few things more boring than seeing some random expert (yes, even me) expound to camera for 20+ minutes (which is, of course, why Dr Who always has an assistant). Hence the producers assembled a delightfully eclectic set of experts for me to talk with on camera, basically with the idea of placing the various deductive leaps I patiently ground out of the academic literature into their helpful mouths:-

Filippo Sinagra, a well-known Venetian code-breaker with a lifelong interest in historical & Mafia ciphers;

Stefano Calchi Novati, a Milanese architect (whose motorbike I sadly couldn’t ride because of insurance issues);

Rosa Barovier Mentasti, a thoroughly delightful glassware expert descended from the Murano glassmaker Angelo da Barovier, but whom I somehow managed not to capture on camera (the image is from Mauro Vianello’s nice glass blog);

A magnificent Murano master glassblower whose name unfortunately escapes me, and whose wonderfully rich Venetian accent proved near-impenetrable even to our Italian translator; and…

Well-known Venetian architect and historian Francesco da Mosto, presenter of several top-rated BBC series with the power to make many British women of a certain age swoon unashamedly.

OK, now that we’ve got past all the raw factuality, what really happened while filming?

3. Nine Top Secret Things That Happened On The Shoot

(1) I’d only previously been to Venice out of season (if you’re going, I recommend December), and July 2011 turned out to be a raging heatwave. Despite that, John Blystone (the director) had me marching back and forth across endless Venetian bridges to the point that I nearly got heatstroke, and had to sit down in a quiet corner eating ice cream for an hour while I cooled all the way back down to merely hot. Note that I don’t hold this against him – John’s a driven guy and wanted to get the best possible coverage going into the edit, and if he can make a bald historian bloke like me come out tolerably OK on camera, I have to say he’s pretty much on fire. 🙂

(2) While getting over heatstroke, I found out that Cesira (the translator) used to run short film festivals, though she bemoaned the fact that Italian film-makers were typically so talky that they thought 20 minutes should qualify as ‘short’. I then told her how I used to write stories in 30 words or less as a writing challenge: she didn’t believe that that was even remotely possible, so insisted I write her one there and then. Knowing that the crew was flying on to Rome to film a Da Vinci-related segment, this is what I squeezed into a mere 15 words:-

“Not again, Lisa!”

“What?”

“Every time you fart, you do that smile.”

“Sorry, Maestro Leonardo!“

(3) While in the Piazza San Marco, I suddenly noticed that the columns of San Marco and San Theodoro were leaning very slightly towards each other. Luckily I managed to straighten them up before any tourists got crushed by falling stones: an excellent result!

(4) I’d be a lying hound if I didn’t say it was more than a bit of a thrill meeting Francesco da Mosto & his lovely family in their Venetian palazzo, and lightly zipping around the canals with him in his near-iconic blue boat. Francesco is an enthusiastic, positive, laughter-filled big-kid-puppydog of a man that made me want to smile every time he opened his mouth: probably half the shots were ruined because we were having too much fun to look serious in an appropriately documentary-style way. I love the guy to bits, and wish him the very best of luck with finishing his historical novel “The Black King” (which, spookily enough, one online description I read said revolved around John Dee and a mysterious enciphered manuscript).

(5) When we got back to San Marco after filming (and eating late) in Murano, the tide was so high that we couldn’t get a boat into the canal near the apartment (“Casa Cioccolata”, a nice little place). This meant the crew had to carry all the equipment barefoot across the waterlogged piazza in the moonlight: a thoroughly surreal experience!

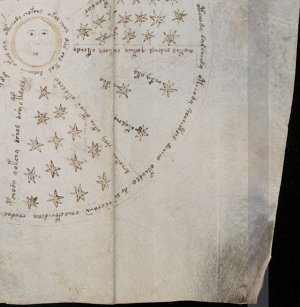

(6) Once nice thing in Venice which didn’t make it into the final edit was that the newly-restored clock tower close to St Mark’s Basilica has a 24-hour clockface Voynich researchers may well find eerily familiar:-

(7) Another scene which didn’t make the final cut involved comparing the pinion gears in that same clock with some of the (remarkably similar) gear-shaped leaves in the Voynich Manuscript. This didn’t quite fit the narrative the producers & editors wanted to extract from “The Curse”, so never made it in. If you do get a chance to take a tour around the insides of the Horologia clock, please do – highly recommended!

(8) While we were filming in Antonio Averlino’s Ospedale Maggiore in Milan, I was showing the curious pipework in the Voynich Manuscript’s Quire 13 to the architect Stefano Calchi Novati when there was a surprised call from around the corner. The sound recordist (Stefano Varini) had noticed some decaying ancient terracotta pipework embedded in the fabric of the building – I knew it was supposed to be there, but had never actually seen it. Thanks to the “access-all-areas pass” a well-accredited film crew has, we had gone through to the far quadrant of the Ospedale that I hadn’t previously seen. It was really wonderful to see for myself what I can only conclude was Averlino’s original pipework still in situ – and that it turned out to be so very similar to the Voynich’s pipework was an even greater surprise.

(9) For me, the most amazing thing of all actually came after the documentary had finished shooting. Late on the last day, I had taken a picture from the right end of the middle wall of the Castello Sforzesco, looking out over the front wall: the reconstructed Filarete tower is in the middle, and the Duomo is clearly visible in the distance just to the right of it.

But it later struck me that if I had taken the same shot from the right-hand corner of the backmost wall (which is the only part of the castello that Averlino is known to have actually built), the Duomo would have ended up looking remarkably like the blue smudge behind the castle in the castle rosette.

Here, all the places Averlino worked are in green, the two rows of swallowtail merlons are in blue, and the place where I think the Voynich castle rosette drawing was made from (the middle of the rear courtyard) is in red. The two red lines mark the extents of the blue smudge just above the Voynich castle rosette.

4. Crew Credits

Seeing as this isn’t even remotely included in IMDb (shame!), I thought I ought to include the crew credits, give them their fifteen seconds of fame:-

Director: John Blystone

Camera: Peter Thorne

Sound: Stefano Varini

Fixer: Dario Canciello

Translator: Cesira de Vito

They were all a pleasure to work with, and I hope to work with them again very soon on the feature-length sequel “The Da Voynich Code” (though possibly not in 3D). 😉

UPDATE!

National Geographic episode rollout (I’ll update this as it propagates through the Nat Geo listings, please let me know if I’ve missed any!):-

* Indonesia: Fri, 11 May 2012 8:00 pm

* Hungary: Titkok és ereklyék (‘Secrets and Relics’): Szodoma és Gomora – 23-24 May 2012.

* UK: 9pm 22nd May 2012, and then several times a day all the way through to the 27th May 2012