USC’s irrepressible Kevin Knight and Dartmouth College Neukom Fellow Sravana Reddy will be giving a talk at Stanford on 13th March 2013 entitled “What We Know About the Voynich Manuscript“. Errm… which does sound uncannily like the (2010/2011) paper by the same two people called, errrm, let me see now, ah yes, “What We Know About the Voynich Manuscript“.

Obviously, it’s a title they like. 🙂

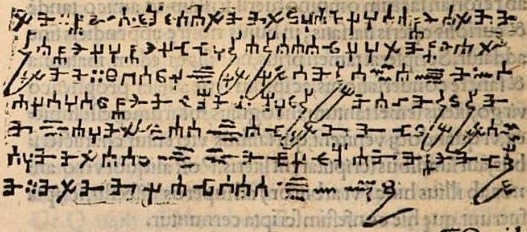

As I said to Klaus Schmeh at the Voynich pub meet (more on that another time), what really annoys me when statisticians apply their box of analytical tricks to the Voynich is that they almost always assume that whatever transcription they have to hand will be good enough. However, I strongly believe that the biggest problem we face precedes cryptanalysis – in short, we can’t yet parse what we’re seeing well enough to run genuinely useful statistical tests. That is, not only am I doubtful of the transcriptions themselves, I’m also very doubtful about how people sequentially step through them, assuming that the order they see in the transcription of the ciphertext is precisely the same order used in the plaintext.

So, it’s not even as if I’m particularly critical of the fact that Knight and Reddy are relying on an unbelievably outdated and clunky transcription (which they certainly were in 2010/2011), because my point would still stand regardless of whichever transcription they were using.

In fact, I’d say that the single biggest wall of naivety I run into when trying to discuss Voynichese with people who really should know better, is that hardly anyone grasps that the presence of steganography in the cipher system mix would throw a spanner (if not a whole box of spanners) in pretty much any neatly-constructed analytical machinery. Mis-parsing the text, whether in the transcription (of the shapes) and/or in the serialization (of the order of the instances), is a mistake you may well not be able to subsequently undo, however smart you are. You’re kind of folding outer noise into the inner signal, irrevocably mixing the covertext into the ciphertext.

Doubtless plenty of clever people are reading this and thinking that they’re far too smart to fall into such a simple trap, and that the devious stats genies they’ve relied on their whole professional lives will be able to fix up any such problem. Well, perhaps if I listed a whole load of places where I’m pretty sure I can see this happening, you’ll see the extent of the challenge you face when trying to parse Voynichese. Here goes…

(1) Space transposition cipher

Knight and Reddy are far from the first people to try to analyze Voynichese word lengths. However, this assumes that all spaces are genuine – that we’re looking at what modern cryptogram solvers call an “aristocrat” cipher (i.e. with genuine word divisions) rather than a “patristocrat” (with no useful word divisions). But what if some spaces are genuine and some are not? I’ve presented a fair amount of evidence in the past that at least some Voynichese spaces are fake, and so I doubt the universal validity and usefulness of just about every aggregate word-size statistical test performed to date.

Moreover, even if most of them are genuine, how wide does a ciphertext space have to be to constitute a plaintext space? And how should you parse multiple-i blocks or multiple-e blocks, vis-a-vis word lengths? It’s a really contentious area; and so ‘just assuming’ that the transcription you have to hand will be good enough for your purposes is actually far too hopeful. Really, you need to be rather more skeptical about what you’re dealing with if you are to end up with valid results.

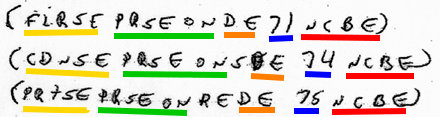

(2) Deceptive first letters / vertical Neal keys

At the Voynich pub meet, Philip Neal announced an extremely neat result that I hadn’t previously noticed or heard of: that Voynichese words where the second letter is EVA ‘y’ (i.e. ‘9’) predominantly appear as the first word of a line. EVA ‘y’ occurs very often word-final, reasonably often word-initial (most notably in labels), but only rarely in the middle of a word, which makes this a troublesome result to account for in terms of straightforward ciphers.

And yet it sits extremely comfortably with the idea that the first letter of a line may be serving some other purpose – perhaps a null character, or (as both Philip and I have speculated, though admittedly he remains far less convinced than I am) a ‘vertical key’, i.e. a set of letters transposed from elsewhere in the line, paragraph or page, and moved there to remove “tells” from inside the main flow of the text.

(3) Horizontal Neal keys

Another very hard-to-explain observation that Philip Neal made some years ago is that many paragraphs contain a pair of matching gallows (typically single-leg gallows) about 2/3rds of the way across their topmost line: and that the Voynichese text between the pair often presents unusual patterns / characteristics. In fact, I’d suggest that “long” (stretched-out) single-leg gallows or “split” (extended) double-leg gallows could well be “cipher fossils”, other ways to delimit blocks of characters that were tried out in an early stage of the enciphering process, before the encipherer settled on the (far less visually obvious) trick of using pairs of single-leg gallows instead.

Incidentally, my strong suspicion remains that both horizontal and vertical Neal keys are the first “bundling-up” half of an on-page transposition cipher mechanism, and that the other “unbundling” half is formed by the double-leg gallows (EVA ‘t’ and ‘k’). That is to say, that tell-tale letters get moved from the text into horizontal and vertical key sequences, and replaced by EVA ‘t’ (probably horizontal key) or EVA ‘k’ (probably vertical key). I don’t claim to understand it 100%, but that would seem to be a pretty good stab at explaining at least some of the systematic oddness (such as “qokedy qokedy dal qokedy qokedy” etc) we do see.

Regardless of whether or not my hunch about this is right, transposition ciphers of precisely this kind of trickiness were loosely described by Alberti in his 1465 book (as part of his overall “literature review”), and I would argue that these ‘key’ sequences so closely resemble some kind of non-obvious transposition that you ignore them at your peril. Particularly if you’re running stats tests.

(4) Numbers hidden in aiv / aiiv / aiiiv scribal flourishes

This is a neat bit of Herbal-A steganography I noted in my 2006 book, which would require better scans to test properly (one day, one day). But if I’m right (and the actual value encoded in an ai[i][i]v group is entirely held in the scribal flourish of the ‘v’ (EVA ‘n’) at the end), then all the real content has been discarded during the transcription, and no amount of statistical processing will ever get that back, sorry. 🙁

(5) Continuation punctuation at end of line

As I noted last year, the use of the double-hyphen as a continuation punctuation character at the end of a line predated Gutenberg, and in fact was in use in the 13th century in France and much earlier in Hebrew manuscripts. And so there would seem to be ample reason to at least suspect that the EVA ‘am’ group we see at line-ends may well encipher such a double-hyphen. Yet even so, people continue to feed these line-ending curios into their stats, as if they were just the same as any other character. Maybe they are, but… maybe they aren’t.

Incidentally, if you analyze the average length of words in both Voynichese and printed works relative to their position on the line, you’ll find (as Elmar Vogt did) that the first word in a line is often slightly longer than other. There is a simple explanation for this in printed books: that short words can often be squeezed onto the end of the preceding line.

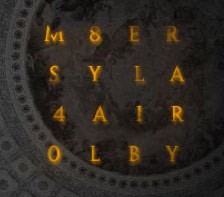

(6) Shorthand tokens – abbrevation, truncation

Personally, I’ve long suspected that several Voynichese glyphs encipher the equivalent of scribal shorthand marks: in particular, that mid-word ‘8’ enciphers contraction (‘contractio’) and word-final ‘9’ enciphers truncation (‘truncatio’) [though ‘8’ and ‘9’ in other positions very likely have other meanings]. I think it’s extraordinarily hard to account for the way that mid-word ‘8’ and word-final ‘9’ work in terms of normal letters: and so I believe the presence of shorthand to be a very pragmatic hypothesis to help explain what’s going on with these glyphs.

But if I’m even slightly right, this would be an entirely different category of plaintext from that which researchers such as Knight and Reddy have focused upon most… hence many of their working assumptions (as evidenced by the discussion in the 2010/2011 paper) would be just wrong.

(7) Verbose cipher

I’ve also long believed that many pairs of Voynichese letters (al / ol / ar / or / ee / eee / ch, plus also o+gallows and y-gallows pairs) encipher a single plaintext letter. This is a cipher hack that recurs in many 15th century ciphers I’ve seen (and so is completely in accord with the radiocarbon dating), but which would throw a very large spanner both in vowel-consonant search algorithm and in Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), both of which almost always rely on a flat (and ‘stateful’) input text to produce meaningful results. If these kinds of assumptions fail to be true, the usefulness of many such clever anaytical tools falls painfully close to zero.

(8) Word-initial ‘4o’

Since writing my book, I’ve become reasonably convinced that the common ‘4o’ [EVA ‘qo’] pair may well be nothing more complex than a steganographic way of writing ‘lo’ (i.e. ‘the’ in Italian), and then concealing its (often cryptologically tell-tale) presence by eliding it with the start of the following word. Hence ‘qokedy’ would actually be an elided version of “qo kedy”.

Moreover, I’m pretty sure that the shape “4o” was used as a shorthand sign for “quaestio” in 14th century Italian legal documents, before being appropriated by a fair few 15th century northern Italian ciphers (a category into which I happen to believe the Voynich falls). If even some of this is right, then we’re facing not just substitution ciphers, but also a mix of steganography and space transposition ciphers, all of which serves to make modern pure statistical analysis far less fruitful a toolbox than it would otherwise be for straightforward ciphers.

* * * * * * *

Personally, when I give talks, I always genuinely like to get interesting questions from the audience (rather than “hey dude, do you, like, think aliens wrote the Voynich?”, yet again, *sigh*). So if anyone reading this is going along to Knight & Reddy’s talk at Stanford and feels the urge to heckle ask interesting questions that get to the heart of what they’ve been doing, you might consider asking them things along the general lines of:

* what transcription they are using, and how reliable they think it is?

* whether they consider spaces to be consistently reliable, and/or if they worry about how to parse half-spaces?

* whether they’ve tested different hypotheses for irregularities with the first word on each line?

* whether they believe there is any evidence for or against the presence of transposition within a page or a paragraph?

* whether they have compared it not just with abjad and vowel-less texts, but also with Quattrocento scribally abbreviated texts?

* whether they have looked for steganography, and have tried to adapt their tests around different steganographic hypotheses?

* whether they have tried to model common letter pairs as composite tokens?

I wonder how Knight and Reddy would respond if they were asked any of the above? Maybe we’ll get to find out… 😉

Or you could just ask them if aliens wrote it, I’m sure they’ve got a good answer prepared for that by now. 🙂