To summarize Part 1, an ex-pirate known as ‘Le Butin’ left a will, two letters, and an enciphered note describing where he had buried treasure on Île de France (the former French name for Mauritius). But even though this is widely referred to as the “La Buse Cryptogram”, I can’t see any obvious reason to connect the pirate Olivier Levasseur (‘La Buse’) with it. Anyway, our story continues…

The documents were retrieved from the Archives Nationales de la Réunion in 1923 for a lady from the Seychelles called Rose Savy(who was descended from Le Butin’s family): she to flew to Paris with it to try to solve its mysteries. In 1934, the eminent French librarian Charles de La Roncière at the Bibliothèque National de France wrote a book about the affair called “Le Flibustier mystérieux, histoire d’un trésor caché“.

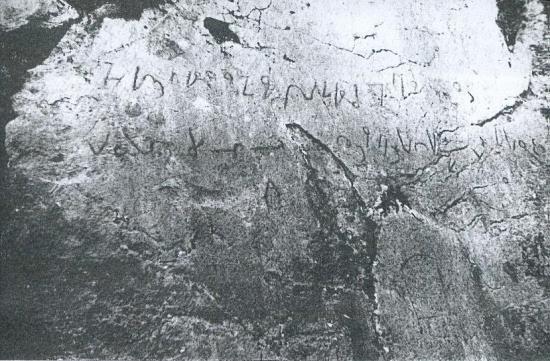

Spurred on by the promise of gold-gold-gold, numerous treasure hunters have poured decades of their lives into this whole, ummm, ‘hopeful enterprise’. Savy herself believed that the answer was somehow connected with some strange carvings that she found on her property, depicting “chiens, serpents, tortues, chevaux“, as well as “une urne, des coeurs, une figure de jeune femme, une tête d’homme et un oeil monstrueusement ouvert“. [Do I need to translate those for you? I don’t think so!]

Reginald Cruise-Wilkins (1913-1977) “had done code-breaking work with the British forces and he found references to Andromeda in Levasseur’s enigma”, says John Cruise-Wilkins, who even today continues searching for the treasure that so obsessed his father from 1949 onwards. Just so you know, John C-W himself “believes [Levasseur] buried the bounty according to a complex riddle inspired by the 12 labors of Hercules”, ten of which he believes he has solved.

Well… another famous Levasseur story goes that as he was crossing a bridge over what was known as “la ravine à Malheur”, he said “Avec ce que j’ai caché ici, je pourrais acheter l’île” – ‘with what I’ve hidden here, I could buy the whole island‘. So perhaps it’s no wonder that people desperately want to believe that there’s pirate gold in (or perhaps under) them thar island hills. [Though as I say, I’m fairly unconvinced that this cryptogram has anything to do with La Buse. But perhaps that’s just me.]

Another famous La Buse treasure hunter was called Bibique (real name Joseph Tipveau, he wrote a book called “Sur la piste des Frères de la Côte”), but who shot himself in 31st March 1995, I’m sorry to say.

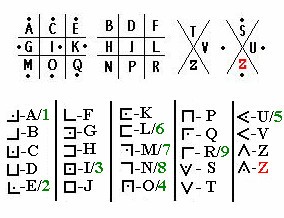

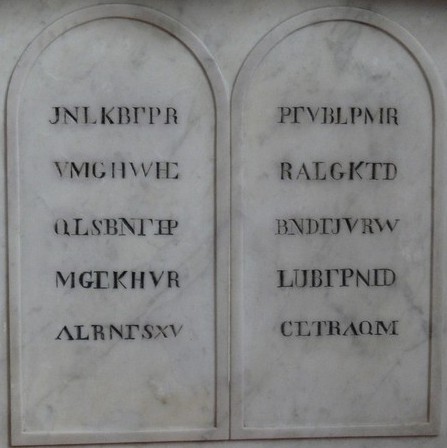

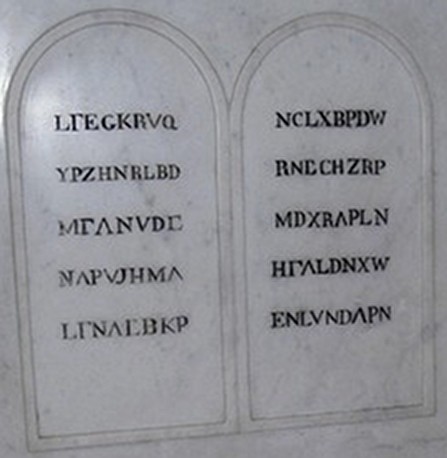

But with my crypto hat back firmly on, I have to say that the cipher system ascertained by de La Roncière could barely be more straightforward: a pigpen cipher, with letters of the alphabet arranged in a very simple manner, and with some of the shapes also used to represent digits (AEIOU=12345, LMNR=6789). Arranged in traditional pigpen style, the key looks like this…

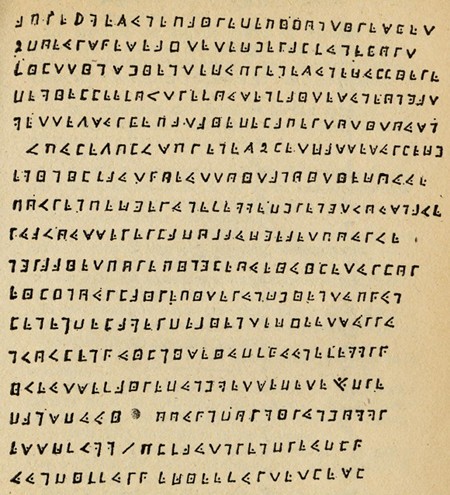

…while the cryptogram itself looks like this (click on it to see a larger image)…

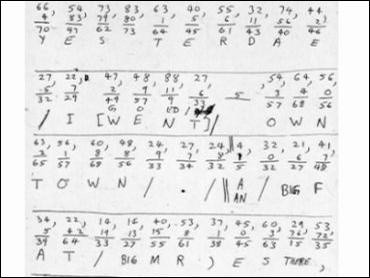

And yet despite all that clarity, the cipher mystery remains, because if you use the above key to decipher the above ciphertext, what you get is an extremely confusing cleartext, to the point that perhaps “clearasmudtext” would frankly be a better word for it. Here’s one version from the Internet with spaces added in for marginal extra clarity:-

aprè jmez une paire de pijon tiresket

2 doeurs sqeseaj tête cheral funekort

filttinshientecu prenez une cullière

de mielle ef ovtre fous en faites une ongat

mettez sur ke patai de la pertotitousn

vpulezolvs prenez 2 let cassé sur le che

min il faut qoe ut toit a noitie couue

povr en pecger une femme dhrengt vous n ave

eua vous serer la dobaucfea et pour ve

ngraai et por epingle oueiuileturlor

eiljn our la ire piter un chien tupqun

lenen de la mer de bien tecjeet sur ru

nvovl en quilnise iudf kuue femm rq

i veut se faire dun hmetsedete s/u dre

dans duui ooun dormir un homm r

esscfvmm / pl faut n rendre udlq

u un diffur qecieefurtetlesl

The best single page presentation of it I’ve found comes from this French site that tries to colour-code the letters. Certainly, there are indeed errors in the text: but I don’t personally think that throwing your hands up and guessing at the correct plaintext values (which is what most treasure hunters seem to do) is methodologically sound.

Far less cryptographically naive would be to try to classify many of the errors as probable pigpen enciphering errors (where, for example, the difference between A and B is simply a dot). The fact that the ‘Z’ shape apparently occurs both with and without a dot implies (to me, at least) that a number of dots may well have slipped in (or out) during the writing. Moreover, there is no suggestion as to which of the ciphertext letters might be enciphering numbers (the two instances of “2” given are actual ‘2’ digits, not carefully interpreted ‘e’ ciphers), and aren’t pirates always pacing out distances from curious rocks etc?

For example, “doeurs” is a mere dot away from “coeurs”; while mysterious non-words such as “filttinshientecu” might actually start “fils…” rather than “filt…”. Might it be that (Voynich researchers will perhaps groan at this point, but…) some of these were emended by a later owner?

Or might it be that the image we’re looking at is actually a tidy copy of an earlier, far scrappier cryptogram, and what we’re most plagued by here is copying errors? I would say that the presence of some composite letters in the text is a reasonably strong indication that this is a copy of a cryptogram, rather than the original cryptogram itself.

Hence I suspect that properly decrypting this will be an exercise rich in cryptology, French patois, and codicological logic. Good luck, and let me know how you get on! 🙂

But after all this time, is there any Le Butin booty left? I read an online claim that several of Le Butin’s treasures have already been found:-

* one allegedly found in 1916 on Pemba Island (part of the Zanzibar Archipelago), allegedly marked with his initial “BN” (Bernardin Nageon)

* one allegedly in Belmont on Mauritius in a cave near the river La Chaux

* one possibly found on Rodrigues (is this the one mentioned in the letter?)

* one allegedly found at a cemetery on Mauritius in 2004, though I found no mention of it in the archives of the weekly Mauritian Sunday newspaper 5-Plus Dimanche.

However, I haven’t yet found any independent verification of any of these claims, so each story might separately be true, false, embellished, misheard or merely mangled in the telling. Please leave a comment below if you happen to stumble upon actual evidence for any of these!