How are we ever going to resolve the mystery of the Voynich Manuscript?

Even sixty years ago, it was abundantly clear to William Friedman (widely believed to be the greatest ever codebreaker) that the Voynich’s cipher/language was of a different type to anything that had previously been encountered, and that normal cryptanalytical tools would be of little use in revealing its secrets. If Voynichese was ‘gettable’, Friedman and then Brigadier John Tiltman (who I personally place right up there with Friedman) would surely have got it, or would have begun to get it: but neither did. Yet high quality scans, several decades of study and the Internet’s million eyeballs have not yet yielded insights significantly beyond what Friedman and Tiltman managed.

And so we fast forward to 2014, where researchers continue to adopt one of two basic paradigms: (a) that Voynichese uses an unknown cipher, and so we must grind through an endless series of statistical tests that must surely eventually isolate an answer, and (b) that Voynichese is written in an unknown language, and so we must extract a set of individual word cribs to identify the language’s family etc.

After a lot of consideration, my opinion is that the Voynich Manuscript laughs in the face of both approaches: and that if you’re using either (or indeed both) of them, you’re almost certainly wasting your time. Moreover, by spamming people with the results of your research, you’re wasting their time too.

Please understand that I’m not saying that these two paradigms are worthless in all circumstances: rather, I’m saying as flatly and directly as I can that though they do have great value in other contexts, they are essentially worthless when applied to the Voynich Manuscript. They have not worked, do not work and never will work for it: hopefully that’s a clear enough position statement.

So… if they don’t work, what’s the alternative? Ay, there’s the rub.

The Block Paradigm

With all the above in mind, it became apparent to me a while back that what was actually missing was an entire paradigm, by which I mean a complete and systematic way of thinking about what we are trying to do with Voynich research, with what tools, and for what purpose. Hence I’ve spent most of this year trying to work out what that new paradigm should be, and to find a good way of communicating it.

(This has basically been why Cipher Mysteries has been so quiet as far as the Voynich Manuscript goes.)

My working title for this new way of thinking about the Voynich Manuscript is the “Block Paradigm”, because as its target it seeks to identify not a letter, a word or even a language, but a block of text. That is, the idea is to use three stages:

(1) identify blocks of the plaintext that stand some chance of appearing in other manuscripts;

(2) find possible matches for them in other manuscripts; and then finally

(3) attempt to reverse-engineer the way that the two blocks map to each other.

As such, the Block Paradigm is entirely neutral about whether Voynichese is a cipher, a shorthand or an unusual language (or any combination of the three): the purpose of the first two stages is to get us to the point that researchers can attempt to do the reverse-engineering third stage for a given block with reasonable confidence that they may have something that could well be the plaintext.

Over the next few weeks, I plan to introduce and discuss a number of candidate blocks from the Voynich Manuscript. Right now, I only have a possible matching plaintext block for one of them (and that’s a particularly complicated block that I’ve been working with for some years), so this is only really the start of what I hope will be a broadly collaborative and productive process.

I’ll start with a candidate block that has already been discussed by Voynich researchers, though not nearly as fully as I think it deserves.

The Poem Block

On 26 Apr 1996, Gabriel Landini posted to the Voynich mailing list:-

Folio 76R has a full body of text, that is, the page is almost completely filled with text. I can guess 4 paragraphs. However if we go to folio 81R, then the text looks like if it was written as a poem. Some lines longer than others and there is no drawing that is restricting the line lengths. I wonder if the pages like 81r are songs, hymns or prayers…

Rene Zandbergen replied (on 29 Apr 1996):

If I remember well […] f81r is unique is this respect. To me, it gives the impression as if a drawing was intended for the right margin, but it has been omitted. This is at variance with the generally accepted theory that all drawings were done first and the text filled in later. Another special feature of this page is that there seems to be a connection of the drawing in the left margin, through the binding gutter, to the opposite ‘page’ (which would be f78v if my above assumption for 81r is correct). […]

The ‘poem’ idea fits well with Currier’s observation that the line seems to be a functional entity. This again is strange in view of the fact that in many cases the text is clearly organised in paragraphs, i.e. several full lines followed by one short line and sometimes a somewhat larger gap between this and the next line. The length of each last paragraph line seems to be anything from one word to a full line. Note that when it is one word, it is sometimes centered on the line.

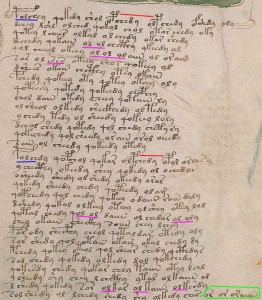

With the benefit of better scans and 18 further years of study, let’s look again at this possible ‘poem’ on f81r and annotate what we see:-

I’ve marked the two horizontal Neal keys (at the top of the two main sections of text) in red, some extraneous-looking text appended to the final line (possibly a date, or a signature?) in green, two almost identical gallows-initial words in blue, and various unusual features of the text in purple.

The text itself seems to have a line structure of 7 / 8 / 8 / 8 lines (as per the ornate line-initial gallows-initial words): so if this is a poem, my prediction is that the poem was originally 8 / 8 / 8 / 8 lines but that an entire line got omitted by mistake during the copying. (Copying ciphers by hand is surprisingly hard to get right).

As for the likely subject matter of the poem, that too isn’t too hard to predict: given that it is sandwiched between two drawings of naked nymphs in baths, it would surely shock nobody if the poem turned out to be about water or baths.

I would also expect the poem to be in Latin or Italian (OK, Tuscan), because those were (as I recall) the languages typically used for balneological poems pre-1450.

So what might the poem actually be? You might think it could be a section grabbed from Peter of Eboli’s famous early medieval Latin poem “De Balneis Puteolanis”: but that, according to C. M. Kauffmann’s “The Baths of Pozzuoli” (p.14) consists of thirty-seven sections (an introduction, thirty-five sections each covering a different bath, and a dedicatory section at the end), each section having precisely twelve hexameters. Hence I suspect we can eliminate De Balneis Puteolanis as a candidate simply because it has a different verse length – we’re looking for eight or sixteen line sections, but it is based around twelve-line sections.

All of which is where my preliminary account of this poem block comes to a halt: I simply don’t know the balneological literature well enough to take this any further forward. Were there any pre-1450 balneological poems written with eight or sixteen lines per section? I believe that this question should probably be the starting point for researching this particular block; but what do you think?