Here’s a partial update on the Paul Emanual Rubin cipher mystery for you, followed by my updated thoughts on the ciphertext, and then finishing with my current best guess as to what happened. But… please don’t build your hopes up too high, there’s no sign of hugely happy ending to it all just yet. 🙁

The Update Part

After my recent post on the Paul Rubin cipher, I discovered that Craig Bauer (whose long-standing interest in the case was the starting point for that post) is currently planning to write and publish a Cryptologia article on it.

Needless to say, I’m really looking forward to his article: and I really hope that he gets to peek just a little behind the veil of the scanty external documentation to reveal the real secret history just behind it. There’s certainly very little of substance currently in the public domain: yet there’s a good chance that many of Rubin’s friends – if Bauer could manage to identify them – may well still be alive. I’m sure that they would be very happy to help Bauer get closer to the truth, even at this distance in time.

At the same time, I’m assuming that the FBI – which was so clearly involved right from the start of this case – will likely not be contributing to the picture Bauer will build up. As a matter of general policy, the Bureau seems uninterested in contributing or collaborating with external codebreakers (and don’t get me started on the Ricky McCormick case), so the FBI side of things seems to be an avenue that will remain blocked for many years yet.

The Cipher Part

Doubtless Craig Bauer will have his own conclusions about the ciphers used (and he may even have access to enough primary material to be able to break the ciphertext). But here are mine.

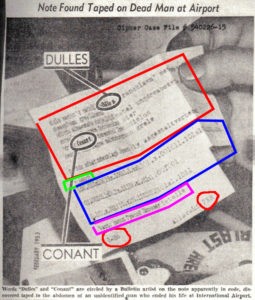

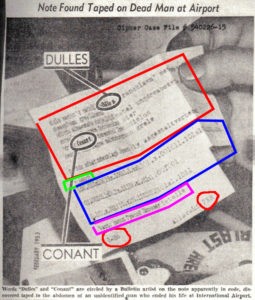

Even on the low resolution photo of the cipher note, we can see “PER” at the bottom right, which is surely Paul Emanuel Rubin’s typewritten signature. Hence there is no real doubt that this whole thing was made directly by him.

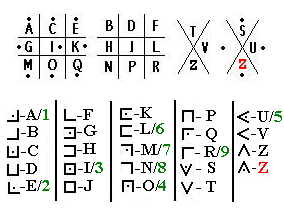

I also have no real doubt about the section with the numbers on (outlined in blue above): that this is a home-brewed Morse Code variant. Only an amateur / kid code-maker would use something like this: while visually impressive, it’s hugely long-winded and impractical.

Finally, I have very little doubt about the section that seems to have “Conant” and “Dulles” in the clear: there is only one cipher system that has sufficient latitude to achieve this, and that is where a plaintext message (or a simple substitution cipher message) gets interspersed with euphonic or orthographically pleasing nulls to generate a covertext. Trithemius proposed this 500 years ago, and I feel certain that this is what is being used here.

e.g. the underlying cipher message might say “C.N.N”, but after nulls get added, the cover message becomes “C.o.N.a.N.t”.

As a more general observation, though, I suspect that each line of the text uses a separate code-table, because there seems to be very little consistency from line to line, even if you take every other letter of each line. But that fits with the whole amateur code-maker thing: it’s almost impossible to break extremely short ciphertexts, unless you have a lot of a priori knowledge about what was going on in context (which seems not to be the case here).

Finally, the other short patches of text seem likely to me to be code-table references or offsets etc. When Rubin’s friend said at the time that he (I presume he) would be able to decrypt it in a few hours if he had access to Rubin’s code-tables, this is without much doubt what he meant. Hence my prediction is that each code-table is relatively simple in itself, but that each one is used only in short bursts, to make it nearly impervious to codebreakers.

The Secret History Part

As to what was going on Rubin’s life and head in the days and weeks up until his death, I don’t honestly know: as I mentioned before, I strongly suspect that he may have been suffering from paranoid schizophrenia (for surely only someone in a distressingly paranoid place would even consider taping a coded message to their abdomen), but many other causes and rationales are still in play.

But I do have a guess about what went wrong after his death.

And this is based on cryptanalysis: that if “Conant” and “Dulles” were, as I believe, both part of a covertext created by filling between genuine cipher letters with nice-looking Trithemian nulls to form additional words, then I don’t honestly believe that the plaintext will ultimately have anything remotely to do with “Conant” and “Dulles” at all. In short, if you were paranoid about Conant and Dulles, you really wouldn’t leave them in plain sight.

But this was the diametric opposite of the assumption that the FBI seemed to be working on in this case. This was 1953, after all, the height of the HUAC and Cold War era, and Reds were perceived to be under every goshdarned Bed. And Rubin was a student, and therefore – so the mythology goes – could well have been exposed to one of numerous radicalizing factors and ideologies. So in fact it seems to me that poor Mr Rubin may not even have been the most paranoid element in the whole setup: by which I mean that the FBI seems to have been institutionally paranoid at that time, paranoia on an almost industrial scale.

Personally, I believe that Rubin’s friends – with whom he had exchanged numerous coded notes, according to various newspaper accounts, and doubtless knew most of his Trithemian tricks well – could easily have broken the heterogeneous set of micro-ciphers that made up his final essage, had they been given access to his code-tables.

However, my suspicion (as things stand) is that Rubin’s friends never got to see the message. Instead, I suspect that the FBI collected up all Rubin’s code-tables and documentation, tried to break them (and failed), and then – because they perceived that National Security was somehow at stake, even if they couldn’t prove it – kept everything quiet. The paranoid logic being, of course, that if Rubin was a goddamn Commie, then all his code-breaking chums were probably all the same distressing shade of Red, and therefore not to be trusted anywhere near his note.

(To my eyes, there are institutional echoes of the way the Ricky McCormick case was later handled, with the (minor) difference being that the institutional paranoia at play there was a weed (ha!) that grew vigorously on top of America’s civil War On Drugs.)

If I’m right, all Rubin’s code-tables are probably still sitting in an FBI archive, having never been shown to the very people who could have helped crack it without much trouble: and if so, what a sad waste of time the whole affair was.

Let’s hope Craig Bauer gets to tell us the whole story.