After my last post, I went looking for a source for the 1896 Airship Flap that concentrated specifically on the reports of flying machines and strange lights in the California sky in late 1896. Specifically, I wanted to know whether there was anything particular about the California sightings that might differentiate the 1896 Airship Flap in California from the 1897 Airship Flap in other states.

Eventually, I found scans of a privately printed book by Loren E. Gross: this had first been published in Fremont, CA in 1974 as “The UFO Wave of 1896”, before being reprinted (2nd edition) in 1987 as “UFO’S: A History 1896”.

Despite the title, Gross’ overall angle was far more Fortean than Ufological. Apart from quoting a local “W.A.” [I read elsewhere that this was “William Ahern”] at the end (who thought that the airship had been sent by “The Lord Commissioner of Mars” [p.27]), the phenomena were largely reported as if they were man-made, with some dissenters thinking it was a hoax.

William Randolph Hearst

In many ways, the story painted by Gross is as not so much about airships and strange lights in the sky as about how the competition between San Francisco newspapers shaped and presented that unfolding history. On one side, The San Francisco Chronicle and particularly The San Francisco Call eagerly searched out airship stories to an engaged public who couldn’t wait for the mysterious airship to do its (much anticipated) Big Reveal downtown so that everyone could see the unknown geniuses behind it. Yet on the other side, William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner went out of its way to rubbish the coverage (particularly from the Call) at every step.

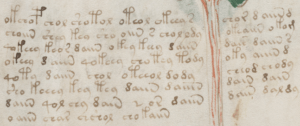

We can see this in a poem (ok, doggerel) in the Examiner 26th November 1896 (reproduced in Gross’ Foreword), where the penultimate verse is aimed squarely at the paper’s competition (might this have been the Call’s editor John McNaught?):

One editor is certain / You really are a ship,

And most adroitly manage / To give his sleuths the slip,

He thinks that now, or later, / The human race will fly;

So can’t you, as a favor, soon / Take him aboard and try?

For if your motive power consists / Of force akin to wind,

He is as large a bag of that / As you will ever find.

The final verse continues the Examiner’s jabbing, basically asserting that the other paper is more interested in profiting from what the Examiner thinks is basically a fake story, designed to catch “suckers”:

Our faith it might be stronger, / But earth is rich in liars

Who do not pause to ponder / The future and its fires.

They’d see a ghost on every cloud / To sell the tale for space,

And spend the price for pie and cake / Wherewith to feed the face.

But come again, oh, toy balloons! / We rather like your style–

We see your catch of suckers / And join you in a smile.

Previously, William Randolph Hearst had taken the reins of the Examiner from his father in 1887 at the age of 17, but by 1896 had switched his day-to-day attention to the New York Journal. Even though Hearst lived on the East Coast, it was well-known that he kept a steely grip on the Examiner‘s editorial policy back in California.

All of which was why The San Francisco Call took so much relish, in late November 1896 at the end the Californian Airship Flap, in pointing out that the two Hearst papers had (in Gross’ words, pp.25-26) “engaged in a two-faced game”. While the Examiner on the West Coast “warred against the Call’s big headlines about mysterious airships by vigorously blaming the aerial visions on people who were under the spell of the Roman god Bacchus”, the New York Journal on the East Coast “excited New Yorkers with sensational tales of powered balloons zipping all over California”.

From the point of view of a modern-day historian looking back at the whole sequence, I think it’s quite clear that there really were plenty of witnesses who saw strange lights in the sky at dusk and at night, many of whom were able to see enough of the shape of the form to identify it as an airship, albeit one with an electric arc-like light and a strange lolloping bat-like motion. The only real reason the Examiner printed so many hoax-y / doubting stories was, I think, to supply a counter-narrative to the Call, not because its editors thought that counter-narrative was actually true.

So, the real battleground here was arguably the bitter American newspaper war of 1896, where Truth was always going to be the first casualty: any pretence at honest reporting was to be jettisoned like useless ballast if it got in the way of elevating Hearst’s newspapers’ circulations yet higher. In fact, my suspicion is that the Examiner‘s dishonest reporting of the 1896 California Airship Flap may well have been what caused so many later writers to erroneously conclude that this was merely some kind of “mass hysteria”. All Hearst’s Examiner needed was a counter-narrative not to inform but to annoy and enrage: you shouldn’t have too far to look these days to find newspapers that still employ this trick to great profit.

The 1896 California Airship Flap begins..

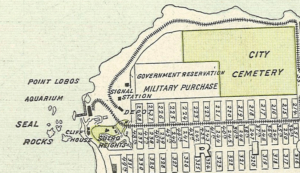

According to Gross, the first substantial sighting of the 1896 California Airship Flap was made by the household staff of silver magnate Mayor Adolph Sutro, at his (somewhat implausible-looking French chateau-style) mansion overlooking the Pacific Ocean west of San Francisco.

It seems a “strange object” had hovered in the air just offshore over Seal Rock. The darkness had masked the features of the unknown aerial thing, but a powerful light had been discernable on the rear portion as well as a row of lights down its side, as the object suddenly flew away toward the east, passing overhead at an estimated 500 foot altitude. [p.1]

We can see Seal Rocks roughly 200m due west of Cliff House in this early map of San Francisco:

What I find hugely interesting about this is that all the key elements of the mystery airship ‘template‘ we see throughout the main 1897 Airship Flap are already fully present here. We have a mystery airship with an unusually strong light (like an electric arc lamp) at the rear, a row of lights down the side, rapid acceleration, dusk or night-time flights, and a flight-path close (but not too close) to large cities and to nearby railway lines.

From a template to a secret history…?

What I’ve been trying to do is to use this template to ‘build’ my way back into the secret history of the device. For what they’re worth, here are my current thoughts:

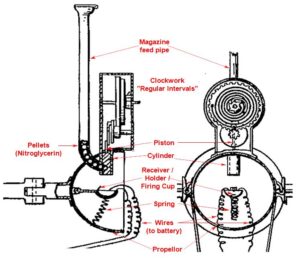

The only practical means of achieving lift available in 1896-1897 was hydrogen gas: but because there are no descriptions of the airship ascending rapidly, my working theory is that it was not primarily intended to rise by dropping ballast, but that it instead used hydrogen gas to achieve neutral buoyancy. I further suspect that it had no air ballonet inside its main gasbags, to control its height above the ground.

In turn, what I think that means is that despite staying buoyant in the air like an airship, it handled more like an aeroplane (i.e. by driving it forward and adjusting its wings to rise or fall slowly in the air) even though aeroplanes hadn’t yet been invented. This mystery flying machine was, in short, a hybrid.

I also suspect that dusk to night-time flights were chosen not primarily for secrecy, but because of technical problems with maintaining stable buoyancy during the (hot) day-time. This makes me suspect that the airship design had practical problems with managing the pressure of its internal gasbags.

Furthermore, I suspect that railway lines were a hugely important part of the airship’s testing process, because they would have provide a reliable means for night-time navigation, and possibly a way for owners to track progress (via messages from telegraph offices, often located near railway lines).

As an aside, an airship flying at 500 feet or higher should have had no fear of running into things: the tallest building in San Francisco in 1896 was the Chronicle Building, which was a mere 120 feet high.

Finally, I think the bright light has to be a huge tell. Anything on board an 1896 airship would have had to have there as a matter of R&D necessity, not as a luxury or a nicety. And the kind of huge battery that would have been needed to power an arc lamp would have weighed (not literally, but not far off) a ton. Hence something else on board must have been creating that intense light, and it must have been creating it for a really good reason.

Having now spent a while trying to link all these strands together, I come back time and again to Dr Sumter Beauregard Battey’s airship design. This was a dirigible based on neutral buoyancy, with means for (what one might call) external combustion to propel it forward (in a moderately steerable way), and with controllable ‘wings’ to adjust the altitude. My suspicion is therefore that what people thought was the “bright light” was in fact actually the flying machine’s means of propulsion, the core inventive step of Battey’s patent.

I also can’t help but wonder if the mystery airship was built elsewhere in California and followed (on this very early test flight to Cliff House and Seal Rocks) the railway tracks going west through Oakland, specifically the Overland Route that headed way across to Nebraska and Iowa. The most obvious location on this line would have been the state capital Sacramento, some 90 miles distant from Mayor Sutro’s gingerbread-style Cliff House. It is perhaps no coincidence that the first newspaper report of a sighting (on the night of the 17 Nov 1896) was by Charles Lusk “at his place of residence at 24th and “O” Streets” in Sacramento [Gross, p.1].

The attorney E. B. Collins, who claimed to be representing the inventor (and whom the San Francisco Call harassed for days), asserted that it started its flight from “Oroville, in Butte County, and flew sixty miles in a straight line over Sacramento”. But… I have to say that I have my doubts that this was true. Dr Charles Abbott Smith at one point was registered to vote in East Bear River Township near Yuba, so I’m actually wondering whether Collins was representing Smith (and I believe that Smith wasn’t yet ready to build anything in 1896).

Thoughts on Gross

I think that Loren Gross did a very good job of bringing these newspaper reports together, and his book offers an excellent (if necessarily all-too-brief) walk-through of the 1896 California Airship Flap: well worth a read!

His first (1974) edition was based on a set of newspaper clippings collected by Vincent Gaddis. His second revision (1987) relied instead on folklorist Thomas E. Bullard’s “The Airship File: A Collection of Texts Concerning Phantom Airships and Other UFOs, Gathered from Newspapers and Periodicals Mostly During the Hundred Years Prior to Kenneth Arnold’s Sighting” and its supplements.

I cannot, of course, find enough words to say how much I now want to see Thomas Bullard’s Airship Files. I’ve contacted Bullard via Academia.edu, but if anyone has any other suggestions as to how I might get to see “The Airship Files” and its supplements, I am – like an overevolved rabbit – all ears.