Today, I have a curious story of a 1957 cipher mystery from Scarborough in Yorkshire, with a flying saucer spin. And – best of all – its secret history has (as far as I know) never been fully revealed.

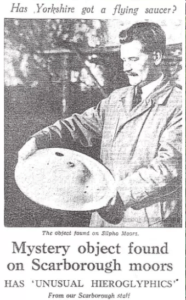

The first press write-up dates to the 9th December 1957, when the Yorkshire Post ran an article (which I haven’t seen) “Mystery object found on Scarborough moors”, “Has ‘Unusual Hieroglyphics’”.

However, most of the contemporary accounts appeared in that august publication Flying Saucer Review…

Three Men in a Car

According to the Flying Saucer Review 1958 Mar-Apr (Vol 4 No 2) p.4:

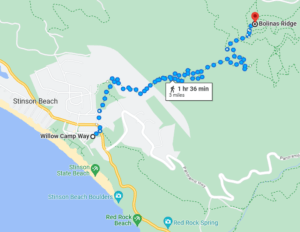

“[…] three men, Messrs. Frank Hutton [a property dealer], Charles Thomas [a butcher] and Fred Taylor [a tailor], were driving up a steep hill on Silpho Moor at night when the engine of the car cut out. They then saw a glowing object in the sky above some trees and it seemed to go right down into the ground.

“Mr Hutton went alone with a torch and found the object in some bracken and then went back to tell the others. On the way he passed a man and a woman on a little used path. When he got back with his friends to the spot where he had found the object in the bracken it was no longer there. After apparently making enquiries they got in touch with the man […]. There was quite a little bargaining and eventually the object was passed over to them for £10. […]

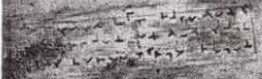

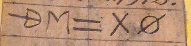

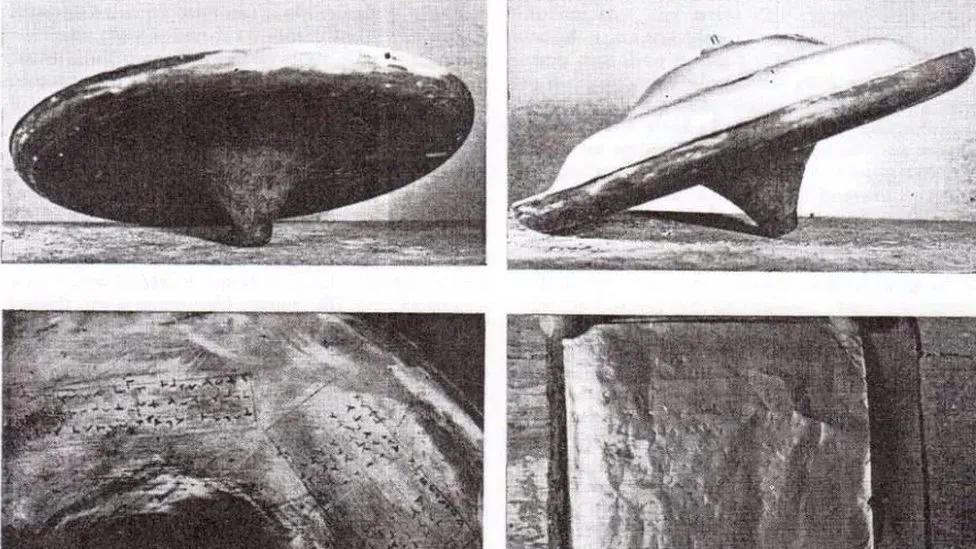

The story continues in Flying Saucer Review 1958 Jul-Aug (Vol 4 No 4) p.19, which helpfully included images of the object (top left, top right) as well as the mysterious hieroglyphics on the outside (bottom left) and some of the 17 sheets of strange imprinted writing (bottom right) that were found inside. These photos were “reproduce[d] through the courtesy of both Dr. James B. Williamson, of Middleton, Manchester, and of the Manchester Flying Saucer Research Society“, and were presumably taken by its President, John Dale:

Though the reproduction isn’t, ummm, out of this world, the first two pieces look like this:

Philip Longbottom and “Ullo”

This object quickly found its way into the hands of an “Anthony Avenel[l]” (actually Anthony Parker, Mr Hutton’s solicitor), who examined the object in the company of a reporter from the local newspaper and Scarborough cafe owner (and ex-electrical and mechanical engineer) Philip Longbottom. Before they drilled into the saucer object to open it up, Avenell had already looked at the imprinted markings on the outside enough to think that it formed some kind of message.

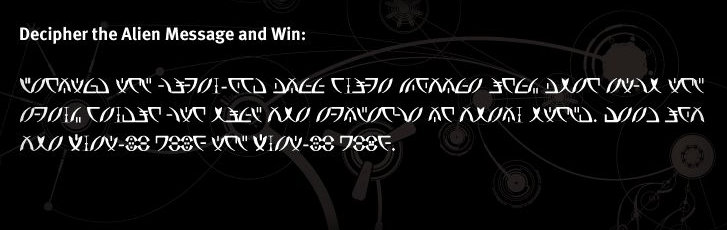

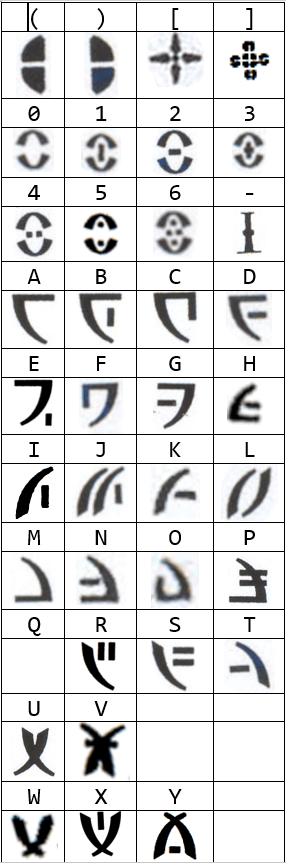

Once it had been pried open, inside they found 17 small copper sheets “joined at one edge”, containing roughly 2000 words of hieroglyphics, in some kind of a cuneiform language. Each letter was formed from two stamped lines, so gave a superficial impression of T, L and V.

Despite knowing nothing about ciphers, Longbottom spent 100 hours decrypting the mystery message: his decryption appeared in the Flying Saucer Review 1958, Nov-Dec (pp.15-17). He wrote:

I took a copy, symbol by symbol, of the key on the outside of the object, and also of the first few lines of the first page of the book, worked through most of the night on this, and finally ended up with a reasonable translation and also, which was more important, was able to evolve a sort of code card, or more elaborate key, to the whole of the heiroglyphics.

[…] It was soon found that each symbol had several alternative meanings and sounds, depending upon its position under, over or across the line or, in some cases, its proximity to the line. Some of the symbols are abbreviations, and several of them are phonetic spellings of familiar words. The whole thing is not just a simple substitution code, but is a very complicated effort. [pp.15-16]

Longbottom added that “the scrolls are now in the hands of a cypher expert, so that we may expect a more accurate translation in the near future, although I expect the gist of the message to remain unchanged“.

He also noted that he had been shown “a paper with heiroglyphics on” by a man called George King (a psychic), “and asked if they resembled those on the scrolls. I replied that one or two were something like them and that is all.” King’s article on this appeared in the April 1957 issue of Cosmic Voice (which I haven’t really summoned the enthusiasm to search for, I must confess).

Longbottom’s “Text of the Scrolls”

My name is ULO and I write this message to you my Friends on the Planet of the sun you call Earth. Where I live I will not say. You are a fierce race and prepare travel. No one from any other planet ever has landed on earth, and your reports to the contrary are faulty. Men cannot travel far in space vehicles owing to sudden changes in speed direction and many other reasons. They are machines, part at out “control”, part “auto-control to avoid objects in way. It is impossible to receive radio over far distances owing to natural waves in space unless key of several frequencies is used, but we can receive single frequencies from near transmitter recorder in space vehicles.

From here to end of message is written by me, Tarngee. I am since three earth years secretary for Ulo who has injured his arm while repairing space vehicle. He lost swimming race with me and I made him tell me reason. Now I write for Ulo. It is friendly if I write about our women. I am of average height. We can’t tell quite your size to compare but I am of height four times across.”

I could transcribe more but personally that’s as much as I can handle before it starts getting really quite silly – but don’t take my word for that, feel free to read Flying Saucer Review for the remainder.

As to whether this decryption was correct, an article by Dr David Clarke (a Sheffield Hallam University lecturer) reports that “Dr [John] Dale also got a language expert at the University to translate the symbols. It was very easy as the code was simple. Based only on a simple L shape in various clock face orientations. Not exactly the product of an extra-terrestrial Einstein.“

Well… OK. But I’d prefer to see the ciphertext and form my own opinion.

The prehistory of the Silpho Moor saucer

When I was researching this a couple of months ago, I found a webpage by someone who claimed that they had seen the same lettering on a fake alien artifact a few months before the Silpho Moor flying saucer incident. Moreover, that preceding artifact had been produced not on Betelgeuse but in Birmingham.

Unfortunately, when preparing to write this page, I haven’t been able to find my way back to that website. If anyone happens to find out where that claim came from, please leave a comment below, thanks!

An epilogue from Paul Grantham?

According to Paul Grantham’s entertaining (and more than a tad skeptical) online account of the above (sadly now only available via the Wayback Machine), an allegedly reliable source told him:

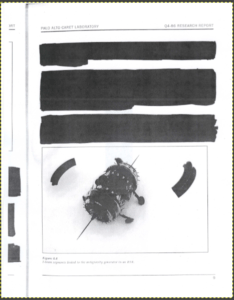

The saucer was in fact one of a batch of secret surveillance objects code named PF228. Three of those launched went astray, two falling into the Atlantic, the other being lost somewhere over northern Britain. He recognised my description of the object as he was working at the base at the time of their launch. They were (he claimed) deliberately disguised as UFOs for the very reason that we discovered. If one were to be found, no-one would believe anyone about it.

It was secretly purchased back from the finders for an undisclosed amount of ‘hush-money’.

Well… I’m not exactly convinced by this, but I couldn’t leave it out, now, could I?

Silpho Moor Bibliography

Isaac Koi’s web page on Silpho Moor helpfully includes a list of book references that discuss the incident.

Moor Questions Than Answers

- If the saucer was in a restaurant for years, where was that?

- Where is the saucer now? (A few fragments turned up in the Science Museum)

- Has anyone got photographs of the message?

- Has anyone got a transcription of the message?

- Who was the languages expert that John Dale passed it to?