Over the years, a small drawing on page 80v of the Voynich Manuscript has triggered what can only sensibly be described as all manner of Unholy Theory Wars.

This drawing has been used as ‘definitive’ proof of the manuscript’s supposed New World origins (i.e. because it is ‘obviously’ an armadillo); or that the manuscript was faked (i.e. according to Rich SantaColoma over at Koen’s blog, “Everybody who was anybody [in the 17th century] had a stuffed armadillo hanging in their kunstkammer“, which may yet turn out to be the Voynich comment of the year); and so forth, endlessly.

Whatever the drawing is actually supposed to represent, all we know for sure is that it appears in a quire / section of the manuscript that seems to be almost entirely related to different aspects of water (there are baths, bathing nymphs, showers, fountains, pipes, and even a rainbow in there). Hence it has long seemed highly likely to me that this will turn out to represent an animal somehow connected to water.

Back in 2009, I suggested as one possible candidate the catoblepas, which nowadays gets far more online attention as a fairly second-rate Neutral Evil Dungeons & Dragons monster (it later became known as a nekrozon, D&D trivia fans), or as a recurring enemy in the Final Fantasy series (it’s called a ‘Shoat’ there, though that actually means ‘piglet’, FF trivia fans) than as an actual mythical beast. Errrm… if you know what I mean.

As an aside, I can’t help but pass on that in Janick and Tucker’s (2018) “Unraveling the Voynich Codex” (whose nutty New World Voynich theory – naturally – relies on this being an armadillo), they mention my 2009 catoblepas page: and on p.360 describe me sweetly as “one of the most expansive and intemperate of bloggers”. Which they can, of course, stick right up their hairy arses, bless them. (Happy now? Good. So let’s move swiftly on.)

But it turned out that Andrew Sweeney had first suggested the catoblepas on the old VMs mailing list back in 2004. Hence I thought it was now time to revisit the entire secret history of the catoblepas, and see what I could find…

Pliny the Elder on the Catoblepas

Our first source is Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79), the well-known Roman writer and naturalist, who is also famous for having died trying to rescue friends and family from Pompeii following the eruption of Vesuvius. He describes the Catoblepas (named from the Greek Κατωβλεψ, ‘looking down’) in his 37-book Naturalis Historia as follows:

In Western Aethiopia [Ethiopia, i.e. West Africa] there is a spring, the Nigris, which most people have supposed to be the source of the Nile… In its neighbourhood there is an animal called the Catoblepas, in other respects of moderate size and inactive with the rest of its limbs, only with a very heavy head which it carries with difficulty — it is always hanging down to the ground; otherwise it is deadly to the human race, as all who see its eyes expire immediately.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 8. 77 (trans. Rackham)

Aelian on the Catoblepas

When Claudius Aelianus (c. 175 – c. 235 AD) wrote his 17-book encyclopaedia of nature, Pliny the Elder’s book was one of many he shamelessly recycled in his own ‘honey-tongued’ prose. So it should be no great surprise that the account of the catoblepas we find there is little more than an elaborated reworking of Pliny’s account:

Libya [Africa] […] produces the animal called the Katobleps [Catoblepas]. In appearance it is about the size of a bull, but it has a grimmer expression, for its eyebrows are high and shaggy, and the eyes beneath are not large like those of oxen but narrower and bloodshot. And they do not look straight ahead but down on to the ground: that is why it is called ‘down-looking’. And a mane that begins on the crown of its head and resembles horsehair, falls over its forehead covering its face, which makes it more terrifying when one meets it. And it feeds upon poisonous roots. When it glares like a bull it immediately shudders and raises its mane, and when this has risen erect and the lips about its mouth are bared, it emits from its throat pungent and foul-smelling breath, so that the whole air overhead is infected, and any animals that approach and inhale it are grievously afflicted, lose their voice, and are seized with fatal convulsions. This beast is conscious of its power; and other animals know it too and flee from it as far away as they can.

Aelian, On Animals 7. 6 (trans. Scholfield) (Greek natural history 2nd Century A.D.):

Thomas de Kent

From there, we fast forward to the Middle Ages and to Thomas de Kent, the Anglo-Norman author of the 12th century Roman de toute chevalerie, one of several Alexander-themed romances written at the time. There are several manuscript versions of his poem (listed on Arlima), of which Trinity College O. 9. 34. (made circa 1250) is online here. However, even though some monsters are depicted in the Trinity Ms, I don’t believe that any of them is a catoblepas, e.g the sea monster on f24r:

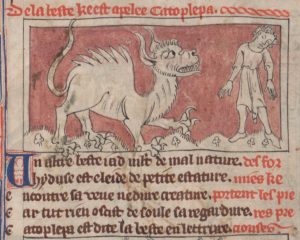

However, the BnF has a digitized copy of the (much more exciting-looking, particularly if you like ornate towers and nicely-coloured horseback battles with swords) 14th century Français 24364, which on fol.68r (in what seems to be an inserted section on mythical animals) has this enchanting image of a catoblepas using its +10 Eyes That Paralyze to kill some poor sap:

Durham’s copy (C. IV. 27 B) I had no luck finding at all, but perhaps others will do better than me.

To be honest, though, this set of manuscripts seems not to have formed the start of any long-running tradition. So this – unless you know better – probably marks the end of this particular line of manuscripts.

Thomas of Cantimpré (c.1200-c.1272)

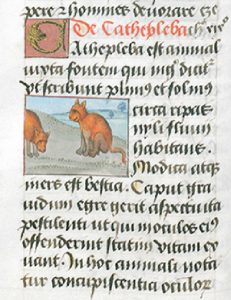

The mainstream medieval reception of the catoblepas seems to begin with Vincent de Beauvais (1190-1264), who mentions it in Book XVIII of his Biblioteca mundi. However it is with Thomas of Cantimpré’s De naturis rerum that things start to get properly interesting.

Even though De naturis rerum was initially just text descriptions, adaptations and illustrations appeared in manuscript copies before very long. And these were then followed by incunabula and (of course) printed books. Hence Thomas of Cantimpré’s book is a lot like the long shadow of the Batcape that falls over Gotham’s seedy streets: by which I mean that just about everywhere we will find the catoblepas depicted from 1300 onwards, it will turn out to be either in a version of De naturis rerum, or in a book adapted from or strongly influenced by it.

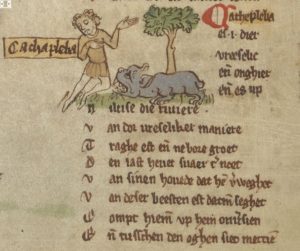

In short, De naturis rerum is the source of the catoblepas Niger. And here’s the ‘cathapleba’ in Valenciennes 320, one of the earliest illustrated mss:

And here’s another (slightly later) one, Brugge MS 411 (1451-1500), found by Ger Hungerink:

Der Naturen Bloeme (ca.1350)

One book adapted (and abbreviated) from Thomas of Cantimpré’s De naturis rerum was Der Naturen Bloeme by Jacob van Maerlant (1230/35-ca.1291). There’s a 2011 edition by Herman Thys, and a detailed 2001 book on its reception by Amand Berteloot and Detlev Hellfaier: in Dutch circles, it’s quite a famous medieval manuscript, so there is plenty of academic literature on it out there if you’re interested.

It is in one of the illustrated copies of Der Naturen Bloeme that we find another early visual representation of the catoblepas. The KB KA 16 manuscript copy (ca.1350) contains miniatures of all the standard Mandevillean monstrosities (people with giant feet, people with no heads, people with two faces, etc), plus an odd-looking catoblepas on this page:

Cathaplebas is een dier

zeer vreselijk en onguur

en is op de Nijl, de rivier,

van de vreselijkste manieren.

Traag is het en niet bar groot.

De last heeft het zwaar ter nood

van zijn hoofd dat hem zwaar weegt.

Van deze beesten is het dat men zegt

komt het op je aan onvoorzien

en tussen de ogen ziet het je

dan ben je weg van het lijf.

Dit dier lijkt op een deel der wijven

die het hoofd dragen gehoornd zo zeer

dat het stinkt voor Onze Heer

en schijnt of het hen verwurgde

dan komt er een dwaas die onge

past op haar ziet en wordt zo gevangen

en van hart alzo ontdaan

dat hij ziel en lijf verliest

en de dood daarom kiest.

Van de c dat neemt hier een einde,

nu hoort wat ik van de d vindt.

In the KB KA 16 copy, Der Naturen Bloeme is preceded by a calendar for Utrecht with local saints’ days (but no Dutch Cisioianus). I should mention that KB KA 16 includes an illustrated zodiac (though no crossbows), plus plenty of marginal whimsy, such as this horny rabbit:

…which is nice.

Here’s another Maerlant catoblepas in the British Library, also found by Ger Hungerink:

Conrad von Megenberg’s “Buch Der Natur”

The other well-known book derived from Thomas of Cantimpré’s De naturis rerum is Conrad von Megenberg’s “Buch der Natur”, which I and Koen Gheuens have both discussed on our respective blogs.

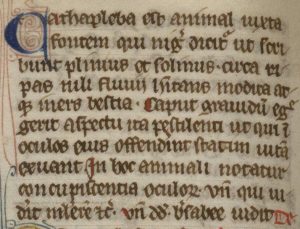

The main reference work for this is Ulrika Spyra’s book “Das ‘Buch der Natur’ Konrads von Megenberg”, a magisterial tome sitting next to me which I have already mentioned here a fair few times. The index references “Cathapleba”, but there’s also Spyra’s extraordinarily helpful “5.2.1 Synoptische Tabelle der Illustrationen in den Buch der Natur Handschriften” (p.382). From this (p.385), we learn that illustrations of the “cathaphleba” are to be found in 68rb of GW (Göttweig, Stiftsbibl., Cod. 389 rot), 83v of HD311 (Heidelberg, UB, Cpg 311), and 87v of M684 (Michelstadt, Nic.Matz-Bibl., Cod. D 684).

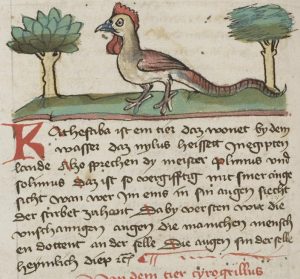

Firstly, Heidelberg UB Cpg311 (1455-1460), because it’s easy to get to. 🙂 However, the surprise here is that the drawing on 83v (reproduced as Abb 35 in Spyra) actually depicts a cockatrice rather than a catoblepas, so isn’t a lot of use to us:

This is copied faithfully in Nurnberg GNM Hs. 16538, fol. 50r (Spyra’s Abb. 47), which is hence also no use to us. 🙂

If anyone can find a copy of 68rb of Göttweig, Stiftsbibl., Cod. 389 rot, or of 87v of Michelstadt, Nic.Matz-Bibl., Cod. D 684, please let me know.

Spyra also mentions (pp.304-305) Olim Erbach, Graflich Erbach-Erbach und Wartenberg-Rothische Rentkammer, Cod. cart. ohne Signatur /Mscr. Nr 2. This has (she says) a Cathehaba on fol 50r.

Leonardo da Vinci on the Catoblepas

Leonardo briefly mentions the catoblepas in his Notebooks, though editors have noted that this derives from Pliny rather than from Aelianus:

CATOBLEPAS.

It is found in Ethiopia near to the source Nigricapo. It is not a very large animal, is sluggish in all its parts, and its head is so large that it carries it with difficulty, in such wise that it always droops towards the ground; otherwise it would be a great pest to man, for any one on whom it fixes its eyes dies immediately.

Marcilio Ficino on the Catoblepas

I found this quotation on p.84 here:

‘Are you surprised that the body of one man is contaminated by the rational soul of another? But you are not surprised that one soul is harmed by another when we gulp down alien vices from the company we keep. You are not surprised that your body is easily infected with disease by the vapor of another body as is obviously the case with consumption, epidemy, leprosy, the itch, dysentery, pleurisy, and conjunctivitis. Among the western Ethiopians purportedly lived beasts called the catoblepas that would kill men simply by looking at them (…), so effective is the power in the vapors of [their] eyes (…). Such is the power of the imagination and especially when the vapors of the eyes are subject to the emotions of the soul’

Ficino, TP, XIII, 4; Allen, IV, 195-197: Ficino, De vita III, XVI; K&C, 325.

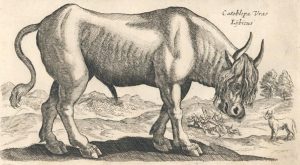

John Jonston (1614)

Skipping past the 16th century (for now), once we get to the 17th century interest in the catoblepas somewhat wanes. Of the two famous 17th century drawings, the first was from John Jonston, which depicts something much closer to the gnu or wildebeest, which was (almost certainly) the source of the original description many centuries previously:

This was from John Johnston’s Historia naturalis de quadrupedibus, Amsterdam 1614.

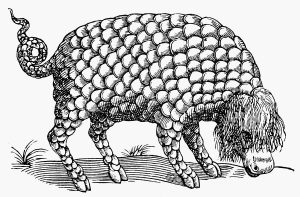

Edward Topsell (1607)

Finally, Edward Topsell’s description of the Catoblepas in his (1607) Historie of foure-footed beastes (which was basically an English translation of Conrad Gessner’s epic 1551-1558 “Historia animalium“) was reproduced in John Swan’s 1643 “Speculum Mundi”, p.649:

The Gorgon or Catoblepas is for the most part bred in Lybia and Hesperia. It is a fearfull and terrible beast to look upon, it hath eye-lids thick and high, eyes not very great, but fiery and as it were of a bloudie colour. He never useth to look directly forward, nor upward, but always down to the earth; and from his crown to his nose he hath a long hanging mane, by reason whereof his body all over as if it were full of scales. As for his meat, it is deadly and poison full herbs; and if at any time this strange beast shall see a Bull or other creature whereof he is afraid, he presently causeth his mane to stand upright, and gaping, wide he sendeth forth a horrible filthy breath, which infecteth and poysoneth the aire over his head and about him, insomuch that such creatures as draw in the breath of that aire, are grievously afflicted, and losing both voice and fight, they fall into deadly convulsions.

Topsell’s drawing / engraving looks like this:

So… What To Make Of All This?

It is, alas, a complicated picture. If there is a common thread to be had, it is that nobody prior to John Johnston seems to have had the faintest idea of what it was they were drawing. Catoblepas get rendered as cockatrices, catty things, doggy things, odd blue things, whatever.

The one detail that got Ger Hungerink most excited was the apparent visual parallel between the Voynich Manuscript’s scaly ‘armadillo’ and Topsell’s scaly catoblepas. But at the same time, I should immediately caution that commentators on Topsell usually conclude that Topsell got confused in his translation, and so merged Gessner’s catoblepas with Gessner’s gorgon.

If you want to read Gessner’s chapter on the catoblepas, it is online here (pp.137-139), though there is no drawing or artwork illustrating it (and the chapter swiftly moves on to discuss the Gorgon). But really, unless someone can dig up a sixteenth century catoblepas print that Topsell could well have referred to, I’m currently not at all sure that we can, on the visual evidence we have so far, trace any kind of viable copying path from any of the Cantimpre versions all the way through to Topsell’s scaly catoblepas.

However, there are still many missing mss above, and there are also two sets of entirely different sources which I still need to go through properly, which I’ll have to cover in a separate post (because this one, I think it’s fair to say, has ended up somewhat out of control). So there’s a little way to go yet…

Here is a far fetched, fun Voynich theory for you Nick: how about the whole thing is an elaborate board game rulebook with the 9 rosette page being either the board or a diagram of the actual board where the game was played? Wouldn’t that explain absolutely everything? It would account for the fantastical nature of the plants, the Amarillo looking creature and even the dragon! i mean, look at the Amarillo and the dragon facial expressions, they are as ludic as can be…How about each plant has imaginary properties that combined in certain ways make special pots that give attack points, vitality, mana points and your RPG, MMO stuff in their very first dawn? What if all those brainy cryptographers haven’t been able to solve it because they are not… GAMERS?

“Expansive and intemperate” ;D

I’m surprised to see that Pliny doesn’t even give any indication that the animal is bovine. Aelian does use a bull but only for comparison, he never actually says that the C. looks like a bull.

Maerlant hardly describes the animal, he goes to the (rather misogynistic) morale of the story as quickly as possible.

So I would rather say that later illustrators are mislead into thinking a bovine creature was meant, while in fact nothing in the source material allows for such a conclusion.

All the better for the VM creature of course, if you think it might be a catoblepas. It beats armadillo for sure.

Apart from all that I’m also very interested in any hard-to-find illustrated Cantimpré MS (and adaptations) that might show up.

Koen: personally, I’m still far from convinced it’s a catoblepas. However, unlike most mythical medieval animals, the catoblepas was still being talked about in the 15th and 16th centuries (as you can see from Leonardo and Ficino here, and even Rabelais and Sir Philip Sydney namechecked it), and it was definitely connected with water: so it’s something that I think we should understand better.

A big side-benefit is that because I’m making my methodology and sources transparently clear here, anyone could repeat basically the same historical research process with any other mythical monster.

So are the wiggly lines water or cloudbands?

With so many candidates for our mystery creature, it seems that some of them fit better with water and others fit better with cloudbands (and it could, I suppose, also be a purportedly aquatic creature perched on a cloudband).

• A beaver (castorum) would fit both water and cloudband. So might a golden fleece (depending on whether the donor ended up as mutton stew).

• Agnus Dei would fit better with cloudband.

• Some of the aquatic creatures that aren’t trying to castrate themselves (there appear to be several candidates) would fit better with water.

…

It looks like a Pangolin standing over a millipede or centipede to me.

@Nick

The drawing on 83v (Heidelberg UB Cpg311) may depict “a cockatrice rather than a catoblepas” but the text clearly describes it as a catoblepas and as an “animal living by the water and called ‘milus’ in the land of Egypt…” Megenberg also refers to the “masters” Plinius und Solinus (De mirabilibus mundi) and the deadly look of the beast’s eyes. So 83v is in fact a valuable source for the fans of that mythological beast.

Charlotte Auer: it’s a very good source, I agree, which is why I included the text with the picture. 🙂 I was only disappointed because I set out to understand how drawings of it evolved in all the manuscript copies, but wasn’t expecting the copyists to have copied completely the wrong animal!

@Erica: It’s not a new theory, see https://xkcd.com/593/ .

It’s a quite convincing article. What I would be interested in, where / who did the transition from the Greek ‘katobleps’ into the Latinized ‘catoblepas’.

LOL Ken! Just thought I’d bring in a drop of geek to dispel some of the too much nerd.

Just imagine someone nowadays finding something like the first map in here:

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/homebrew-dungeons-and-dragons-maps

What an unsurmountable mystery! A gamer would be the only one who would have the key.

Geeks have a lot of what most nerds lack: imagination. Nerds stick to what has been discovered regarding science in their own time, Geeks travel through time. Nerds are synchronic, Geeks are diachronic. Nerds are syntagmatic, Geeks are paradigmatic. In fact, my favorite article in this whole blog is the one about the block paradigm. It proposes a perfect methodology and a very solid platform for research that doesn’t stay swamped in the synchronic time of the manuscript but allows it to find connections in a “diachronical” travel through time.

Thanks for the pictures and the history. I posted redundant material on your May 29 entry on the “armadillo.” I’m wondering if the catoblepas, basilisk, Gorgon may have been confused or fused earlier than Topsell, hence the scales in this little picture of a creature associated with water filled with women. Whoever or whoevers covered this ms with pictures certainly had a cornucopia of myths to draw from. It’s also possible that you will never find a picture from which this creature’s been copied. Things circulate orally and get translated into whimsical marginalia.

Hi Sarah, thanks very much for dropping by, hope you’re ok. 🙂

One of the points I tried to make in the post was that commentators on Topsell – whose 1607 book was basically a translation/encapsulation of Gessner’s works – say with almost one voice that Topsell clearly fused Gessner’s descriptions of the catoblepas and gorgon (which both immediately follow each other in Gessner) into a single faulty description: and that the 1607 illustration is without any doubt an interpretation of Topsell’s fusion.

On the one hand, I can clearly see how the final drawing (and indeed the drawing in the Voynich) resembles a catoblepas to our modern eyes: yet on the other hand, all the pre-Topsell catoblepas drawings I’ve found are many times more like wonky cats/dogs (or even miscopied cockatrices) than Topsell’s drawing.

Ultimately, though, I suspect that our modern eyes are probably more of a hindrance than a help here: and so the lack of any pre-Topsell catoblepas drawing must surely tip the evidential balance against there being any connection between the two catoblepas(es). At the same time, there are lots of other sources to consider as well, which is what I’m hoping to cover in Parts 2 & 3…

Might be this critter with neck and paws. Don’t be misled by the sheep clothing. https://www.museumplantinmoretus.be/de/content/manuskripte

Citing Nick above:

“It is in one of the illustrated copies of Der Naturen Bloeme that we find another early visual representation of the catoblepas. The KB KA 16 manuscript copy (ca.1350) contains miniatures …”

Actually it is the “Alches”: Because its upper lip is that long it needs to walk

backwards while grazing. Van Maerlant’s “Cathapleba” is given here:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/catoblepas.htm

Ger Hungerink.

The Catoblepas was thought to have been based on a Gnu, Wildebeest: the Gorgon taurinus.

“The blue wildebeest was first described by English naturalist William John Burchell in 1823 and he gave it the scientific name Connochaetes taurinus. (…) Though the blue and black wildebeest are currently classified in the same genus, the latter was previously placed in a separate genus, Gorgon [Gorgon taurinus.]”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_wildebeest

Because a Catoblepas could kill by looking at someone, it was sometimes called a Gorgon after a similar property of the Greek Gorgons.

“Gorgons were a popular image in Greek mythology, appearing in the earliest of written records of Ancient Greek religious beliefs such as those of Homer, which may date to as early as 1194-1184 BC. Because of their legendary and powerful gaze that could turn one to stone, images of the Gorgons were put upon objects and buildings for protection.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorgon

Ger Hungerink.

More on the catoblepas (Nick, it might have escaped your attention):

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/Gesner%20etc.htm

Ger Hungerink

Posted already on the Armadillo page, this may be usefull here too:

Having done some photoshopping, please have another look at the f80v creature:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/catoblepas-tail.htm

In the first image move the mouse over the picture to see an accentuated tail, or off it for the actual drawing.

It does look like a hairy tail…

Added are two rotated pictures of the Catoblepas for a better view at its head. It has a pointed snout and pointed ears or horns? No discussion as to it having its head down. According to legend, ready to look up and kill with its breath or eyes…

Ger Hungerink.

Ger Hungerink: thanks for that. Just so you know, Part 2 is planned to cover the catoblepas in other manuscript traditions, and Part 3 the catoblepas in incunabula and 16th century books (such as the ones you mention). But these are both relatively big projects, so will take a little while to complete. :-/

Knox: your link seems to have lost its attached critter. 🙁 Can I please ask you to find it again and repost the link here? Thanks!

Nick: The link on your page worked for me this morning after I cleared the browser cache. Try these:

Magnifieke Middeleeuwen’ toont unieke collectie verluchte handschriften

https://nieuws.kuleuven.be/nl/2013/magnifieke-middeleeuwen-toont-unieke-collectie-verluchte-handschriften

Magnifieke middeleeuwen in het Museum Plantin-Moretus/Prentenkabinet

http://vlaamseprimitieven.vlaamsekunstcollectie.be/nl/nieuws/magnifieke-middeleeuwen-in-het-museum-plantin-moretusprentenkabinet

The scales of f80v might not be scales at all. Birds often have this pattern in feathers and four-footed beasts are sometimes depicted with hair in such a pattern. A striking example is the lamia with a similar f80v tail. And almost the same body as f80v.

For more examples see:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/Lamia.htm

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/Lamia%20historyoffourfoo00tops_0369.jpg

Ger Hungerink

The identification of the ‘critter’ is one aspect to consider, but there is more to it than that. There is also the line structure drawn directly beneath it and the consideration as to how that part might be interpreted. (As mentioned in J. K. Petersen’s comment of 13 June)

Actually, the primary line, with its bulbous crests and troughs, fits the heraldic definition of a nebuly line. The traditional term, ‘nebuly’, derives from the Latin ‘nebula’ for a mist or cloud. And a corresponding etymological derivation occurs in other European languages. In German the line is gewolkt, derived from ‘Wolke’, also referring to clouds. This may imply that the line structure should be given some sort of cloud-based interpretation.

Whatever the critter’s identity, and whatever the line structure’s interpretation, the two parts should probably fit together. Therefore it does seem unlikely to find a catoblepas among the clouds, unless the VMs artist was a real joker.

Out*of*the*blue, you will find that this curvy line is sometimes used as the rim of a parasol, definitely not as clouds. Te curvy line underneath the “catoblepas” has a range of vertical strokes that seems to support it, strokes similar to the strokes in the parasol leading to the rim.

But you might think it to be rain. Do your German “Wolkenbands” show this rain too? In other places though these curvy lines clearly are the border of a pond. Or show the nymphs surrounded by it, including the vertical strokes. When they are in Heaven, what it might show, why would there be no catoblepas in Heaven?

The page showing hairy animals that have their fur drawn like “scales” has been updated to include many more examples. Even the Voynich rams more or less show a similar pattern:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/Lamia.htm

This ram from the Aberdeen Bestiary MS 24 ca 1200 is one of the examples:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/scaled%20ram%20-%20Aberdeen%20Ram.jpg

Ger Hungerink.

So it’s just the Great Bear?

Ruby….not a bear. But it is also a forest animal. Clever animal. And it has scales like fish.

You must know the meaning of the symbol – fish.

Then you understand what the animal means. And who is it.

Ruby Novacna said: “So it’s just the Great Bear?”

It is a possiblility.

But almost certainly it is not a fish. Its tail does not have that shape and is far too little anyway for its prime purpose: to swim.

Four-legged sea monsters typically have a tail that is about as thick as the body at the position of the hind legs. Just like the lizards, pangolins, dragons, etcetera.

This page has been updated to show some examples:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/catoblepas-tail.htm

Ger Hungerink

Ger,

A regular line with bulbous crests and troughs fits the heraldic definition of a nebuly / gewolkt line. The terms nebuly and gewolkt derive from the Latin / German words for cloud, respectively. Therefore the cloud-based connotation is inherent in the etymology. Now that we know this, the cloud-based interpretation should be *considered*.

Does it always work? Of course not. But then look at the VMs Cosmos (f68v3).

Out*of*the*blue, like I said, the wiggly lines in the VM could be a lot of things, including “wolkenbands”. My problem is the vertical lines underneath – both with the creature and the nymph above it. My question was: are there examples of these “heraldic” wolkenbands with rain? Especially since in the VM these wiggly lines elsewhere seem to produce “radial rain” like in the “parasols”.

I used to see the wolkenbands as clouds, but i now see the ones in quire 13 to be shorelines, similar to the Tabula Peutingeriana. If the animal is an ibex, and represents the alps, then this shoreline places the hind leg well. The parasol looking example is the Rann of Kutsch, a shallow area north if the Bay. The rain signifies that the waters eventually make it back to the sea.

Ger,

I’m not sure, but it seems to me you are blurring the distinctions in a number of different matters regarding wiggly lines, nebuly lines and cloud bands, but that’s not really the question, is it?

It’s about the other little lines. And that sort of had me stumped. However there is another recent blog about the critter and its ‘situation’.

J. K. Petersen’s blog:

https://voynichportal.com/2019/06/15/pinning-down-the-pangolin/

In the last large image, there is definitely something descending from the cloud-band that appears to be rain and wind .

Also three images earlier, the dark blue colored illustration with the lamb in the vesica piscis, lined by another style of cloud-band, if you look closely, there appear to be a number of small red markings scattered below, which would seem to be intended to be interpreted as blood of the lamb.

So it may be that there are several ways to interpret the VMs critter, etc. and perhaps the VMs illustration is intentionally ambiguous.

What about the “missing” Capricorn?

Capricorn was drawn as a goat and often woolly. That might explain the scales pattern of f80v. More about this here: https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/Lamia.htm

It has straight(er) horns like f80v in contrast with rams. It is also known as the “Sea-goat”. It is drawn sometimes as a terrestrial goat, sometimes half goat half fish. That might explain why the scribe associated the fur of his goat with the scales of a fish.

See how compelling that idea seems to be…

Capricorn – Claude Paradin, DEVISES HEROÏQUES (1551)

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/Capricorn%20-%20Claude%20Paradin,%20DEVISES%20HERO%C3%8FQUES%20(1551).jpg

More about the Sea-goat:

http://www.celticmythmoon.com/zodiac.html

So would the f80v be the capricorn from the missing(?) January (and February) page? The pose of the capricorn might be its attacking stance like here:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/fightinggoats.jpg

Also note the short straight horns

Please see more examples here: https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/capricorn.htm

Ger Hungerink.

Like with Koen’s site the Claude Paradin picture link went mysteriously wrong. Another try:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/Capricorn%20-%20Claude%20Paradin,%20DEVISES%20HERO%C3%8FQUES%20(1551).jpg

Otherwise try paste and copy, or see it here:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/capricorn.htm

Out*of*the*blue, in the pictures you mention it is clearly the other way round: there the wiggly lines are obviously clouds so the strokes must be rain. In the VM it is claimed that because the strokes are rain the curves must represent clouds. I am not convinced. Especially because in the VM exactly the same curvy lines definitely do not represent clouds with rain because the strokes radiate like in the “parasols”. e.g. f75r and f75v, or the cuve denotes a pond f82r, etcetera.

Whatever, if it is rain, the creature should not be associated with water but with clouds or heaven. Like the zodiac…

The sea-goat might be a possibility (it is often written in medieval manuscripts as capri-pisces “goat-fish”).

I looked through my zodiac files (I have collected 550+ medieval zodiac cycles). Ten percent of them are goat-fish, the others are mostly goats. I didn’t see any with curled up heads, but the tail is frequently curled.

They rarely draw the tail with scales, however. It’s usually drawn like a seashell or with decorative patterns. Sometimes it’s a dragon-tail.

So, if the VMS critter is a sea-goat, it’s quite different from the others.

Ger,

You said the VMs interpretation is rain > therefore > clouds.

That is not correct. Look at Wikipedia: heraldic lines of division.

The line in the VMs is a line in which the individual troughs and crests are bulbous. This fits the heraldic definition of a nebuly line. The term ‘nebuly’ derives from the Latin ‘nebula,’ meaning cloud or mist. German heraldry uses the term ‘gewolkt’ derived from “Wolke’ or cloud., same as Wolkenband = cloud-band.

Therefore the cloud based interpretation is etymologically inherent in the traditional name of the line.

Occasionally an artist will use a nebuly line to represent water. Occasionally an artist will use a wavy line in a cloud-band. That does not alter the fact that this is a uncommon choice.

Whether it is rain or not is hard to say. The VMs can be somewhat ambiguous.

The VMs illustrations, in comparison to other images of that time (IMO) often show a tendency to correspond in structure , but differ in appearance (as in the cosmic comparison).

In this case, the VMs has a three part structure, a critter, a nebuly / gewolkt line with cloud-based connotation , and a ‘precipitate” . This is the same construction, the same three parts in the same sequence as the illustration I mentioned previously.

Has anyone ever thought that it might just be a pillow?

Peter: do you not know the history of the pillow? 😉

Nick, yes, I just saw and read it, but there were no dead animals on it. 🙂

Forgotten: it looks like you just wanted to bury the poor animal

Peter, I blogged that it might be a pillow. Pangolins and aardvarks were kept as pets. And it might just be a frill around the bottom.

But I don’t think it’s the best explanation because of the way it’s positioned in relation to the other drawing elements, I think the possibility that it’s a cloudband (or something like it) is a higher than a pillow. Look at the lines underneath it.

Ger the motif we call a ‘cloudband’ marks the line between the human domain and that of – call it ‘the divine’ whether referring to non-Abrahamic polytheist or the later-come Abrahamic religions’ belief in one god.

This is why it can serve to demark that line by the cloud-bands or by the strand between the land as the human domain and the sea which was always considered alien to human life. (There’s a whole wonderfully poetic strand in early Christian literature which makes a reverse metaphor of it, with ‘the tumultuous and inimical environment’ being equated with secular life, and the monastery as the truly safe and natural world). However, that’s the thinking whenever this type of line occurs, and what recalls to an impression of the parasol, having such a border, also accords with older beliefs about the blessing of being shielded by clouds and rain from the fierce gaze of heaven. Northern lands naturally envisage the sun as good, and life-giving, but those in other regions have an opposite view and in Islamic custom, as in ancient Egypt or in desert Africa, the parasol embodied the idea of being shielded and saved from harm, whether as evil or as just punishment for transgression. In Arabic, I am told, to be forgiven is expressed as to be ‘covered’.

In that way, a cloudband, or the cover of fresh waters, provided a parallel for the formal emblem of the parasol as token of the high and/or the holy, as it still does (for example) in Ethiopia.

I agree with you that one of the details where the cloudband is used is made to resemble a ‘parasol’ or covering of that sort, and described it so in treating that folio an other uses of the ‘peg and parasol’ motif as long ago as 2010. In fact the series of posts was called ‘Peg. Pole and Parasol’.

The creature which Nick is comparing to Roman literature’s Catoblepas was not a creature of those intangible or ambiguous margins of the earth, though of course our friend JKP speaks my mind in saying that the Voynich creature might be supposed to inhabit both.

Were there a celestial ‘catoblepas’, or even a marine one physical or allegorical, then Nick’s effort to link it to the Vms image might be stronger.. at least imo.

JKP: do you really believe that “… it might be a pillow. Pangolins and aardvarks were kept as pets.”? Sub-Saharan animals as pets pillowed on velvet and silk in the early 15th century in Central Europe? Do you have any reliable source for this assertion?

D.N.O’Donovan: as for the cloudband (in German *Wolkenband*) there is no need for extravagant mysticism as an alleged evidence for a Non-European origin of the VM. Cloudbands are very common stylistic characteristics to depict either spheres or water (and also islands for example) and will be found in many – mostly German – medieval codices. The wave-like structure may be more or less decoratif or elaborated, the meaning always remains clear and simple and is standard in medieval iconography.

Charlotte, did you read my whole message? I said immediately after that that I thought it was a less likely explanation than others and that I’m leaning more toward cloudband than pillow. I said the same in my blog.

But even so, yes, I have reliable sources for these assertions. There are multitudes of medieval images of exotic animals like monkeys, foreign lizards, tropical birds, and cheetahs, etc., etc., many with leashes and pillows, even in early medieval English manuscripts.

Aardvarks were native to Ethiopia and many European products (including herbs) came from Ethiopia. It was regularly included on medieval maps, probably because it was considered a pilgrimage locale, often with a little row of European style castle icons leading to it.

There are numerous writings about nobility actively hunting for exotics to add to their collections (including elephants and giraffes, even though giraffes are nervous animals and very difficult to transport compared to the smaller friendlier critters).

As in many cases of the imagery in quire 13, i see the cloudbands as morphing from one meaning to another, alternatively indicating clouds, shallow water, shoreline, or ephemeral indications, whether it be something to do with religion, or being removed in time and space, or both. I guess the frill on pillows or parasols is another possibility. Depending on the narrative, some or all could be related, and meant in turn.

In some browsers the text of my “catoblepas-tail” page mentioned here before was invisible (black on black)

That has been dealt with:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/catoblepas-tail.htm

My thoughts on the f80v creature have been put together now:

https://hungergj.home.xs4all.nl/catoblepas/f80v.htm

Ger Hungerink

Just like that, to think about it.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2307699969452644&set=gm.2162747927168330&type=3&theater&ifg=1

@Linda

If you look at the whole picture, you are not that far away. It’s not directly related to religion, but science and the church have often discussed it.

It may be similar to an animal, but it never will be for me. Neither Pangolin or another mystical animal.

This is as inappropriate for me in the book as a lawn mower in a butcher shop. You could certainly use it for minced meat, but just, just inappropriate.

JKP, sorry, but your “Pangolins and aardvarks were kept as pets.” sounds as if they were common pets in common households what was surely not the case. Pets as such weren’t common at all.

I’m very familiar with medieval imagery and therefore also with the appearance of exotic animals in illuminated manuscripts over the centuries. Especially the almost naturalistic miniatures in the most beautiful *droleries* are really impressive. But these kinds of book have nothing to do with the VM or vice versa.

The little Voynich critter may rest on a pillow or jump on the beach, without a textual description it remains a small animal without context and no significant hint to its origin.

A simple idea: the lady takes a bath while her cat curls up on a cushion nearby.

The rendition of fur approximates roughly to this image –

https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=6907

In passing – my latest blog.

https://www.science20.com/patrick_lockerby/understanding_the_voynich_manuscript_3-239762

In my next I will list many more Latin words.

ydaraiShy = comes ars avestum / vastum

companion art improve / master

The VM is promoted in the first paragraph as a book of knowledge of the art of creating perfumed oils.