I’ve posted on so many separate Tamam Shud / Somerton Man topics recently (which have in turn triggered so many comments), I thought it might be a good idea to at least try to tie up a few loose threads still dangling here. “Ne’er does one door close but that another opens”. (Am I the only person who remembers “The Horrors of Ivan”?)

1. A Professorial Plug

As I mentioned here recently, the Unresolved Mysteries subreddit will be hosting an AMA (“Ask Me Anything”) session with Professor Derek Abbott this Saturday. If you log in there then and post questions, he promises to try to answer them.

To be precise, the AMA session will start at the following (time zone) times:-

– Eastern Standard Time: Saturday, 30 August 2014 at 9pm

– Mountain Daylight Time: Saturday, 30 August 2014 at 7pm

– Pacific Standard Time: Saturday, 30 August 2014 at 6pm

– Australian Central Standard Time: Sunday, 31 August 2014 at 10.30am

– Australian Western Standard Time: Sunday, 31 August 2014 at 9am

– New Zealand Standard Time: Sunday, 31 August 2014 at 1pm

– Central European Summer Time: Sunday, 31 August 2014 at 3am

– British Summer Time: Sunday, 31 August 2014 at 2am

Of course, the timing is (let’s say) somewhat suboptimal for European Somerton Man fans: but it is what it is, and if you do want to take part, I’m sure you’ll find a way. 🙂

If you do, here are a few good questions to warm him up with…

* How come the Somerton Man was clean-shaven?

* How come he only had a pastie for lunch and dinner?

* Do you accept the new evidence in Feltus’ Chapter 14 “A Final Twist”?

* Can the dead man’s lividity be reconciled with his position posed on the beach?

* Did anybody ever try to track down the strappers that first found the Somerton Man’s corpse?

* Why did the Somerton Man have no socks in his suitcase?

* etc etc etc 🙂

2. The Australian Codebreaker

While following up the whole how-was-the-Rubaiyat-photograph-made question, I noticed that it was sent to “decoding experts at Army Headquarters, Melbourne” (26 July 1949, Feltus p.108) and that on the next day a “Navy ‘code cracker’ was tackling the task this afternoon” (Feltus p.110).

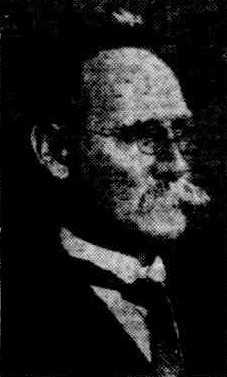

It struck me that these news stories can only really be talking about one person: Captain Theodore Eric Nave, who his biographer Ian Pfennigwerth dubbed “Australian Codebreaker Extraordinary” (in the 2006 book “A Man of Intelligence”). I personally found this a good read, but I suspect that the details of Eric Nave’s Japanese code-breaking exploits probably proved a bit heavy on the technical cryptology side for most lay readers.

Nave was on loan from the Royal Navy to the Australian Army for eight years until 1st January 1948, when he was “attached to the Defence Signals Bureau as a serving officer”, though his “loan appointment was terminated 17:3:49”. When the Australian Security Intelligence Organization (ASIO) was established on 16th March 1949, Nave was proposed as a possible director: however, in those paranoid times the job actually went to a Brit: Nave was instead given the role of Defence and Services Liaison Officer, starting 15th December 1949. (Incidentally, he was also appointed to the board of the Victorian Mission to Seamen in 1950, just so you know).

I feel confident that, even though Nave had managed to accrue 160 days of untaken holiday by June 1948, he was at his desk in Melbourne when the Rubaiyat photograph came in – would they honestly have given it to anyone else in the building? Would they hell, I say.

But did Nave ever write about it? And did Army Headquarters keep a copy of that photograph? Even though Pfennigwerth’s book mines many different archives, Nave’s years immediately post-war seem far more sketchy than his war years, as far as evidence goes. All the same, wouldn’t it be nice if one of these archives proved to have a little bit more of an answer for us?

3. A Close Shave?

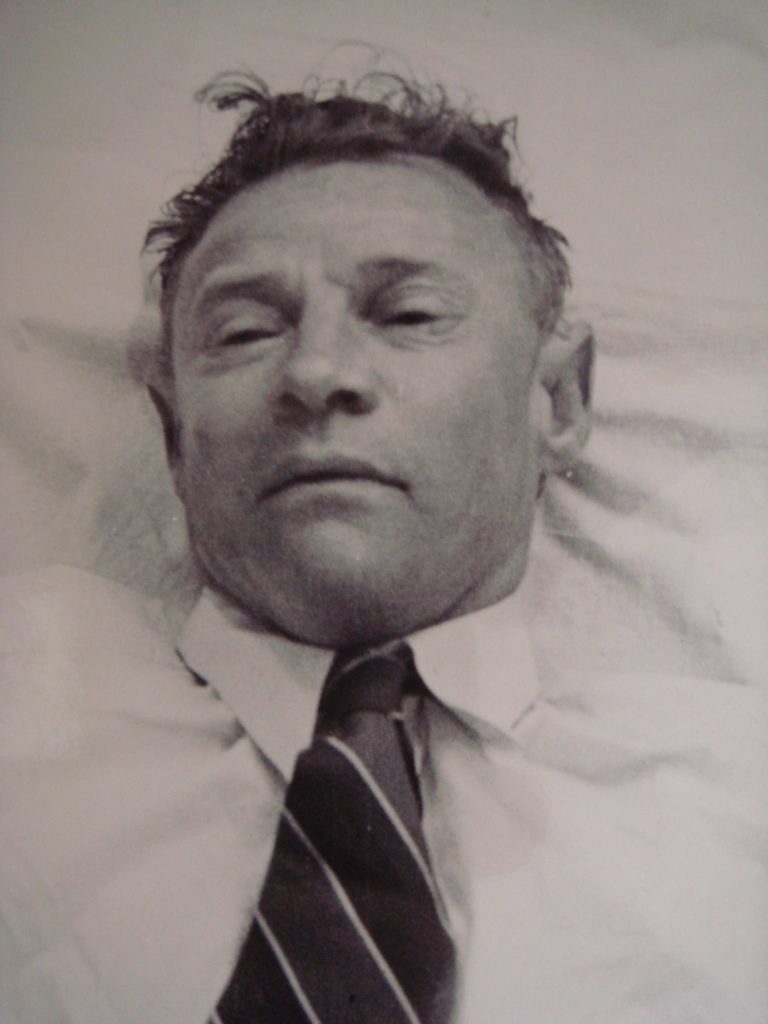

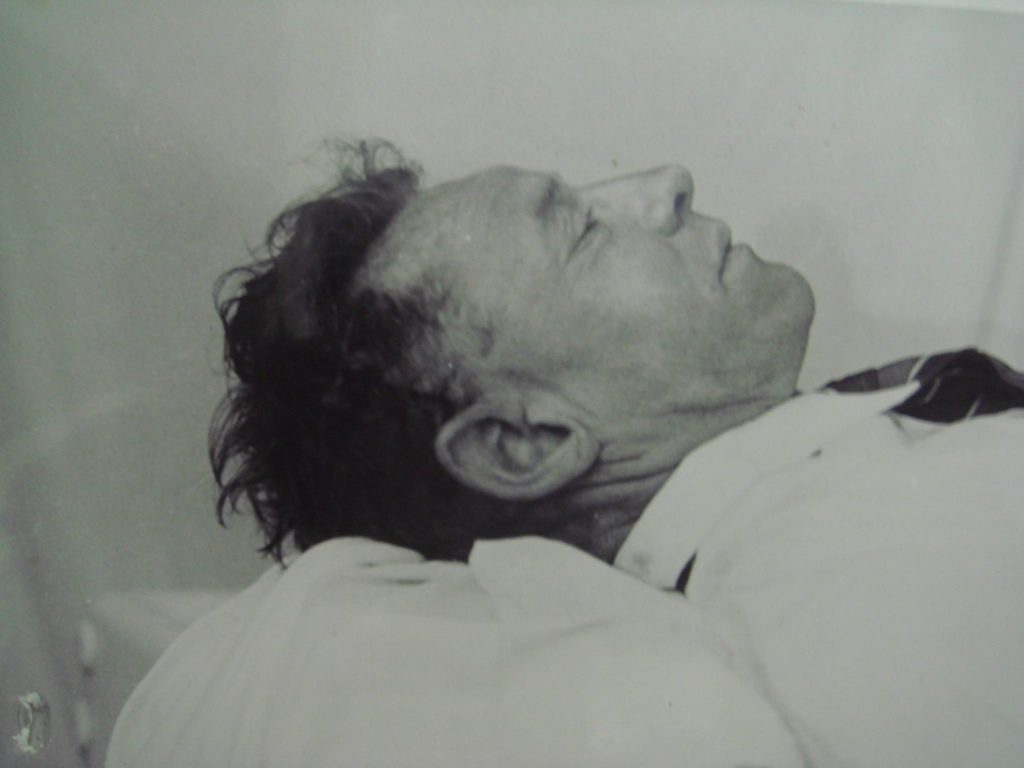

When I posted about how the Somerton Man was oddly (given the generally accepted timeline) clean-shaven, I proposed that he might have had a long-standing beard shaved off that morning.

With the help of the numerous commenters (and having thought about this a bit more), I can see now that I was being a bit hopeful: ultimately beard science says that hair growth is probabilistic, so there ought to have been a normal mix of all three hair phases in his stubble.

And yet at the same time that doesn’t really square with the timeline and what we see. Even so, there are plenty of other possible explanations we can’t rule out: e.g. the man’s face was shaved in the morgue before the photographs were taken (which is possible); he was shaved later in the day; he was in the throes of such a debilitating (and terminal) condition that his body didn’t have the strength to grow any hairs that day; he in general grew hair slower than most people; he had pale ginger facial hair which didn’t show up as 5 o’clock shadow; and so on.

Who knows which one was right? 🙁

4. The Football Player

When I posted about Mrs John Morison, the Adelaide Mission to Seamen’s relentless hospital visitor, I noted that her daughter Mary Morison married a footballer called Ian McKay, and listed highlights of her life up to 1954. The reason for this particular cut-off date is simply that this is currently as far forward as the Australian newspapers archived in Trove go: 50 years back from 2014 is 1954, and any newspaper more than half a century old is deemed to be out of copyright there (just so you know).

But it turns out that Ian McKay was an Australian rules footballer of great repute, who even has a Wikipedia page devoted to him. Unfortunately, the links given there have withered and died on the webby vine: but not before being picked up by the Wayback Machine. So, according to his obituary, we know that when he died in 2010:-

“Ian is survived by his wife, Mary, and three children, Heather, Andrew and David.”

Hence it’s entirely possible I might yet speak with a member of Mrs John Morison’s family before long, which could well prove to be hugely interesting.

Finally, here’s a picture of Ian McKay at (quite literally) the height of his career in 1952:-