Last year, I was contacted by a young French guy called Emmanuel Mezino: he was writing a book about the famous “La Buse” cryptogram and treasure, and asked if my publishing house Compelling Press might publish it. From my experience with “The Curse of the Voynich”, I told him that if he structured it in two distinct halves – the front half summarizing facts and historical research (giving sources), and the second half comprising his inferences and speculation – then yes, I would be very interested.

My rationale for this was simple: even if readers happen to disagree with every single aspect of the reasoning (which, let’s face it, is often the default position with cipher mysteries), the book would still stand a good chance of being hugely interesting, entertaining, and useful in its own right – the story of La Buse is fascinating and intriguing, and I have found few properly historical accounts that do justice to any phase of the pirate’s life.

However well-intentioned that was, it was perhaps too tightly-fitting an editorial straitjacket for a young writer to want to wear; and so Emmanuel ended up editing and publishing his book himself, giving it a romantic-looking cover:-

For its title, Mezino used the phrase allegedly called out by Olivier Levasseur (‘La Buse’) en route to the gallows, as he (so the story goes) threw a piece of paper containing his cryptogram to the crowd – “Mon Trésor à qui saura le prendre” (i.e. “My [fabulous] treasure [will go] to he who will take it”). Buying it will cost you rather less than the bejewelled gold cross of Goa: 18,00 euros (plus postage) for a physical copy, or (perhaps more likely if you happen to live outside France) 11,99 euros for the ebook.

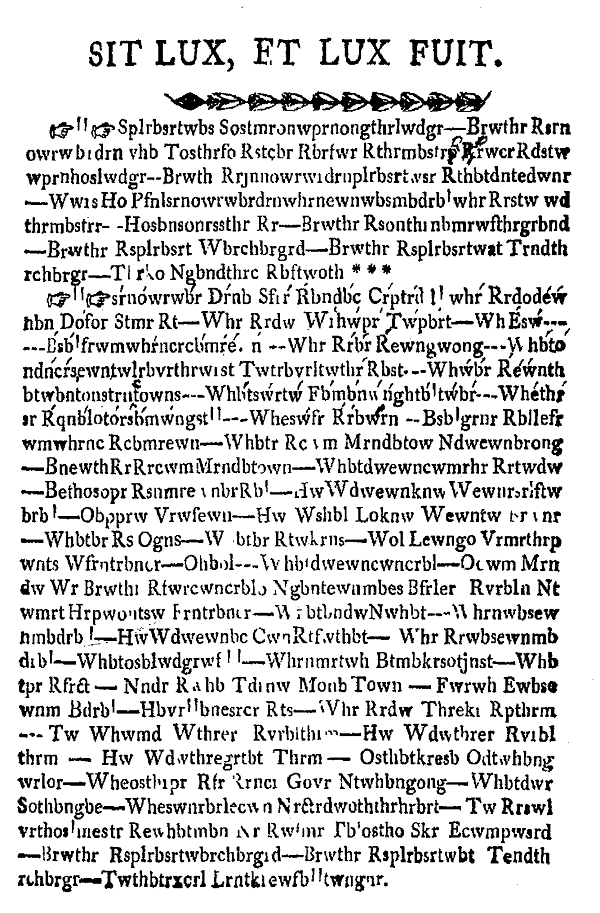

Without much doubt, I think the best bit about the book is that it includes some close-up photographs of parts of a new cipher document – what could very possibly be a second copy of La Buse’s cryptogram. It’s not a perfect scoop (a low resolution colour version of this was included on page 8 of Liz Englert’s (2013) treasure-hunting omnishambles book “My Adventures of the Famous La Buse Treasure“), but the quality of the scans Mezino includes is on the whole extremely good.

Having said that, armchair treasure hunters will be perhaps less than fully impressed that Mezino somehow fails to include a close-up of the lines of cipher that only appear in this second version of the cryptogram, settling on giving merely his interpretation of what those extra letters say (which may or may not be correct).

Another less than satisfactory section was Mezino’s imaginative rendition of the “La Buse” legend, which for all its liveliness was plainly derived from a variety of unreliable sources (apparently including his interpretation of the drawings around the second cryptogram). Though this wasn’t as bad as Pauline B. Innis’ (1973) “Gold in the Blue Ridge” (a teeth-grindingly dreadful imaginative historical reconstruction of the Beale Papers story, which I wearily read recently), I’m not planning to return to either any time soon.

And it should be no surprise that, for all Mezino’s claims that he has (by collecting together an assortment of markings on rocks scattered across the northern half of Réunion; interpreting them as a star map written on land; reconciling that with sacred-geometry-style details overlaid on the cryptogram itself; and then back-linking everything to the astronomer Hevelius) logically deduced the only possible answer to the cryptogram… I’m more than just a bit skeptical. In fact, I don’t think there’s even a single detail in his reasoning that I’d ‘fess to agreeing with.

But as you’d expect, Mezino brooks no disagreement with his Grand Plan: and as writer and editor, that’s ultimately his right. You buy his book or you don’t, and you agree with him or you don’t. It’s all fine.

For me, though, his account is all a bit of a missed opportunity: pictures aside, he’s included all the stuff I’d have left out, and omitted all the stuff I’d have put in. There’s no critical appraisal of the second cryptogram as a source document (or even, dare I say it, as a possible modern forgery made to impress treasure hunters), nor any critical appraisal of La Buse’s own history and the quality of the sources.

Nor is there any kind of critical assessment of La Buse’s earlier life in the Caribbean, nor Le Butin’s trustworthiness as the (alleged) source for the first cryptogram, nor a critical assessment of Charles de la Roncière’s (1934) “Le Flibustier Mysterieux”, which first brought the cryptogram to the world’s attention.

Many Cipher Mysteries readers will doubtless link all this with my recent grouchy post about The Voynich Manuscript for Dummies, where I moaned about how people tend to fixate on the mythology of cipher mysteries, and seem to have no time for looking at the basic historical dimensions of the claimed evidence – transparency, reliability, agenda, bla bla bla. Well, yes: and it would be hard to deny that Emmanuel’s book has ended up somewhat hollow in this respect, which is a big shame.

But even so, I do appreciate that writing an evidence-centred cipher mystery book that manages to keep a properly analytical cutting edge but without destroying the underlying mystique is a really tough writing brief – perhaps almost impossible for a writer’s first book. Ultimately, though, perhaps Mezino’s book will – for all its many shortcomings – prove to be a useful first step in the right direction. Hopefully: and yet from where I’m standing, we’ve got a very long way to go on that road just yet…