Amager Bryghus (that’s the brewery) has just announced “Somerton Man’s Last Drink” which, as an 8.2% ABV wheat lager, may well be enough to make anyone with an enlarged spleen drop dead on the spot, whether or not their clothes have labels. They say (tongue firmly in cheek):-

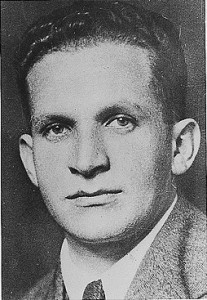

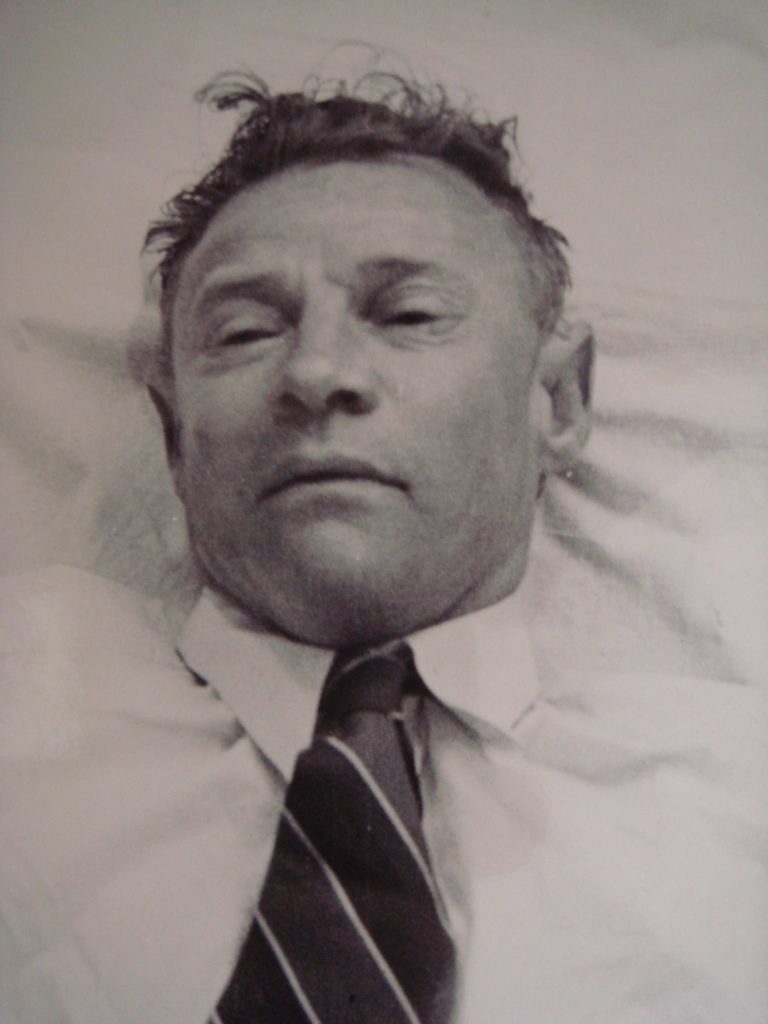

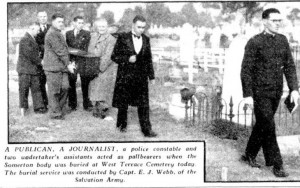

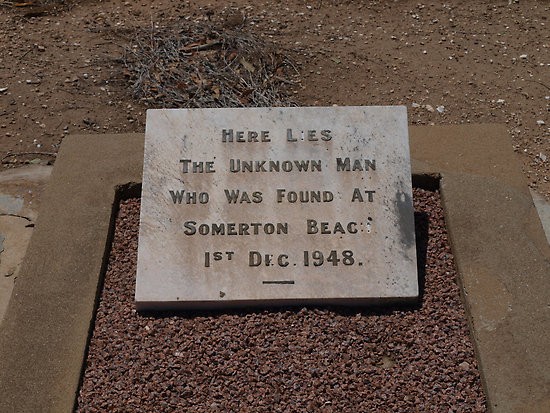

56 years after he was found dead on Somerton Beach in Adelaide, Australia, no one knows who the Somerton Man was or what he died of. A case wrapped in so many layers of mystery that no one has yet been able to penetrate to its core.

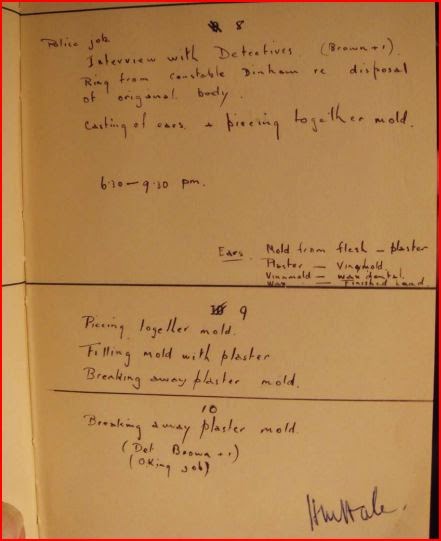

However, a thorough post-mortem examination was performed. In fact, SO thorough that it could be inferred that, just hours before his death, the Somerton Man had eaten a meat pie and drank at least two schooners of beer. Via several questionable detours, we here at Amager Bryghus got hold of his autopsy report, from which our master brewers managed to reconstruct the last beer that the Somerton Man drank on this earth. Our hope is that when drinking this rich and powerful wheat beer, you will also be possible to achieve a high level of creative intoxication – and who knows, maybe solve this 56 year-old murder mystery.

Ingredients: Water. Malt: Pilsner, Wheat. Hops: Amarillo, Centennial, Chinook. Yeast: Warehouse.

Of course, all of this is what they would like to be true, rather than what was actually true. The Somerton Man would have had to knock back far more than two schooners of beer before 6pm closing time for them still to be noticeable, given that his estimated time of death was more than six hours later. And it was lumps of potato that was noticed in his stomach (so a pastie rather than a meat pie).

But honestly, none of that bothers me one jot. The Amager people get a double thumbs-up from Cipher Mysteries for even considering the idea, let alone faking up a back story. You’re totally rock and roll, you funky drunk Danes, you!

Incidentally, my favourite barley-wine-ish strong UK beer is Robinson’s “Old Tom”: which I only mention because Robinsons also released a 4.3% golden bitter called “Enigma”, which is about as close to marrying beer and ciphers as I’d seen before.

But now I’ve seen Amager Bryghus’s effort, I’ve gone looking for other cipher-related beers, and found the Telegraph Brewing Company’s 4.0% “Cipher Key Session Ale”, about which they say “Our Cipher Key Session Ale cracks that code with hefty additions of Cascade hops (etc)”… but they would, wouldn’t they?

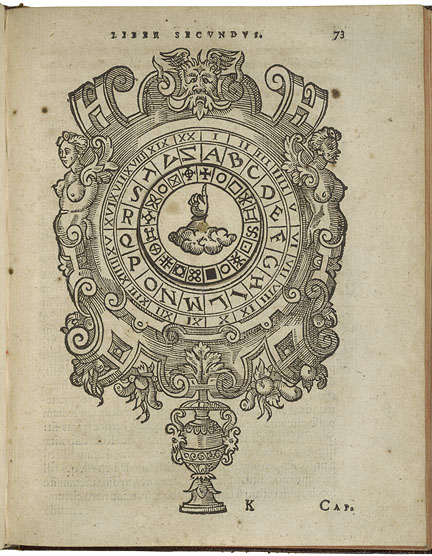

Yet so far I’ve only found one cipher beer with an actual cipher, and that is from the Half Acre Beer Company of Chicago, IL. It’s called “Cipher” (well, duh), and here is its label:-

Can you solve this? More importantly, can you solve it without printing it out and cutting it up into pieces? Enjoy!

PS: are there any other cipher-related beers I should know about? %^,