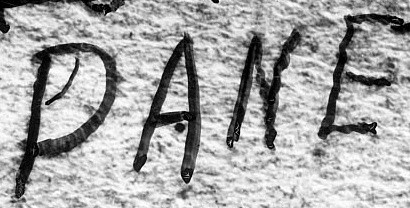

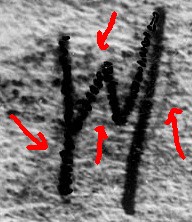

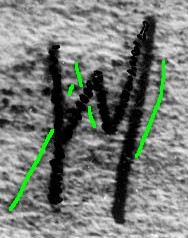

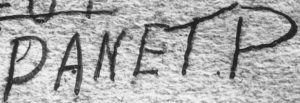

In Part One I looked afresh at the ink of the Somerton Man’s Rubaiyat letters, trying to get some kind of handle on what it is that we are looking at there.

However, I think there’s a huge slice of mid-century history that we’ve largely managed to overlook up until now, but that may well give us a different angle again: Australian police photography.

The ‘mother lode’ of this is a huge collection of about 100,000 negatives taken by NSW police photographers “between 1912 and the late 1960s”: this was originally uncovered in a government warehouse in 1989, but has since had books written about it, as well as travelling archive exhibitions and countless reproductions in newspapers. (It is now under the custodianship of the Historic Houses Trust of NSW.)

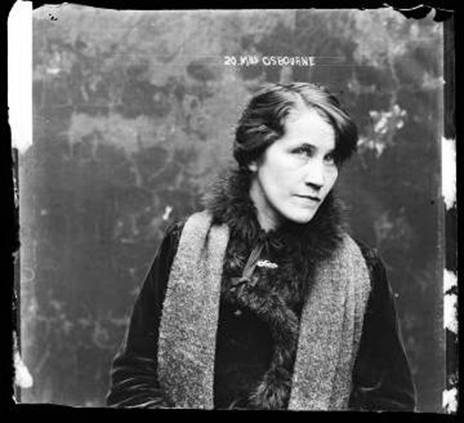

Fingerprints, crime scenes, mug shots, stolen goods, and (yes) even documents are there: the dead, the gloating, the defensive, the beaten, the defiant, the lost. All human life is here, though (with a nod to Anthony Burgess) perhaps the Holy Ghost remained just out of shot. Some appear strikingly anachronistic, such as the extraordinary Mrs Osbourne, who looks to me like someone circa 2009 with a thing for retro clothes:-

There’s a great description online by Peter Doyle of the research he did into this collection, that turned into his (2005) book “City of Shadows, Sydney police Photographs 1912-1948”, as well as his (2009) book “Crooks Like Us”. Perhaps a little media-theoretic for my personal taste, but stunning, unforgettable images nonetheless. (There are a fair few more online here.)

Anyway… from my reading so far, it seems that almost all police images prior to the 1950s used 6″ X 4″ glass plate negatives: it was only in the late 1940s and early 1950s that sheet film started to be used (roll film didn’t arrive until the 1950s). The white writing on the images (such as “20. MRS OSBOURNE” above) was black writing written directly onto the negative (and hence which came out white when turned positive). Text was normally, I believe, written back to front on the negative so that it would end up the correct way round when finally printed, which I suspect is why many of the captions look somewhat scratchy and upright.

We can therefore (I think) already rule out the suggestion that what we see in the Rubaiyat note might have been applied directly to a negative, because (as you can see from the archives) this was a practice used extensively with dark ink that ends up white when the negative is turned positive (as opposed to white ink that ends up dark when reversed).

We can also (I think) rule out the use of iodine vapour deposition to make the photograph: this was an early forensic technique that took the lipids left on a surface in fingerprints and (briefly) turned them brown, whereupon they could be photographed and used as evidence. However, the drawback with this technique is that the lipids left behind in this way degrade and become unusable after only a week or so: so it would seem unlikely to have been used on the Somerton Man’s Rubaiyat.

(This also answers the often asked question about why the Somerton Man’s suitcase was never fingerprinted – it’s because iodine vapour deposition isn’t much use after a week, and the suitcase was only retrieved several weeks later).

We can also (I suspect, though Gordon Cramer will doubtless disagree) rule out the use of UV photography. Even though the Australian Special Investigation Bureau was formed in 1938 (it had access to up-to-date photographic equipment, and developed a “standard set of procedures for taking crime photos” according to this page), I simply don’t believe the photographer used by the SA police was in that league at all.

So what are we looking at, then? If the back part of the image isn’t a film or glass negative, we only really have three feasible scenarios left:

(1) the actual object itself, with an acetate film placed on top of it (and drawn on)

(2) a positive (developed) photograph of the image, with drawings made directly on top of the photograph

(3) a positive (developed) photograph of the image, with an acetate film placed on top of it (and drawn on).

Gordon Cramer also suggests that the photographic image may have been reversed and overexposed to yield more contrast: it’s a possibility, but I suspect we should get the opinion of a photographic historian who properly understands the nuances of mid-century dark room practice, because the image might well be good enough for an expert eye to tell.

Right now, I’m not sure which scenario will turn out to be the right one: but I suspect that there may well still be sufficient clues in the image to assist us in this. For example, it looks to me as though there is some kind of ‘clip’ in the top right hand corner of the image: might that be for holding the original image flat, or for clipping an acetate on top of the image?

Perhaps taking a closer look at some of the 1940s NSW police photographs will help to make this clear. Something to think about, anyway. 🙂