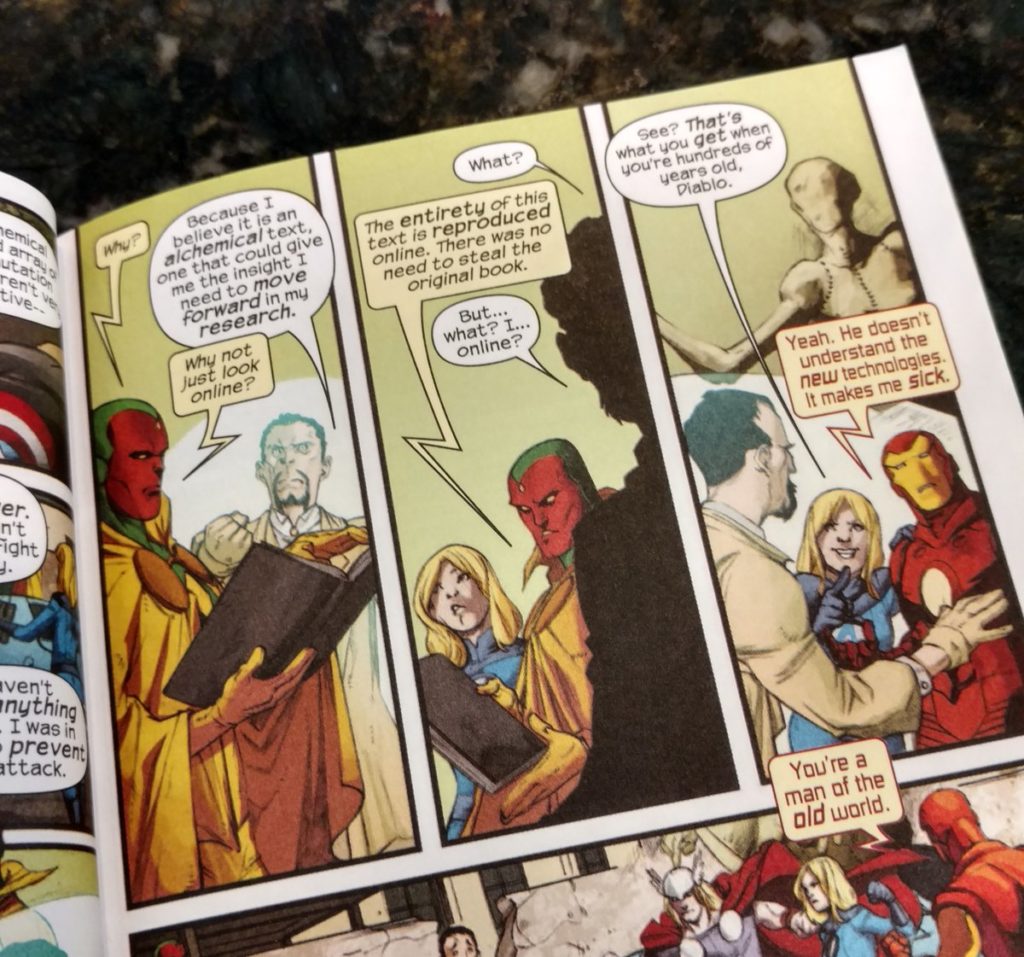

Surely hoping to emulate the stunning success of sideburns and urban beards in recent years, Gordon Rugg is now apparently trying to revive his old papers on the Voynich Manuscript, along with the fame on the world stage that they brought him before.

He has therefore recently co-authored a paper in Cryptologia – Gordon Rugg & Gavin Taylor (2016): Hoaxing statistical features of the Voynich Manuscript, Cryptologia, DOI: 10.1080/01611194.2016.1206753 – which I’m perfectly happy to cite, simply because I immediately append my opinion of it, both then and now: that it is specious quasi-academic nonsense that only an idiot would be convinced by. And any academic referee who read the paper and thought it sensible is an idiot too: sorry, Cryptologia, but it’s just plain true.

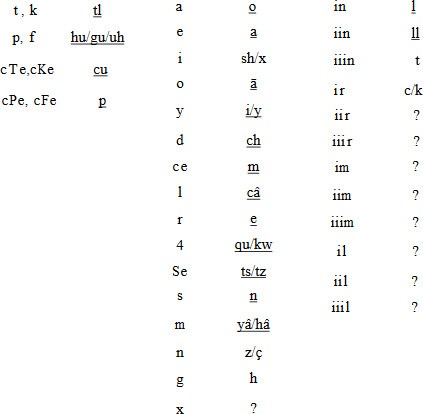

Rugg once again argues – just as he did 12 years ago – that the Voynich Manuscript must surely have been hoaxed using a set of tables and grilles (broadly similar to Cardan grilles, a mainstay of popular books glossing 16th century cryptography) to ‘randomly’ select word-fragments from those tables, while yielding the visual appearance of the ‘Currier Languages’, specifically the Voynich Manuscript’s two main ‘dialects’ (or, as Currier himself would have preferred to say to avoid being misunderstood, ‘statistical groupings’).

Because these tables and grilles allow people to quickly generate hoaxed text mimicking the structure and statistics of Voynichese, he and his co-author Gavin Taylor triumphantly conclude (much as Rugg did before):

“The main unusual qualitative and quantitative features of the Voynich Manuscript are therefore explicable as products of a low-technology hoax, with no need to invoke an undiscovered new type of code and/or the presence of meaningful text in the manuscript.”

In my opinion, this was a dud argument in 2004, and – given all we have learned about the Voynich Manuscript in the decade and more since – it’s an even bigger dud in 2016. Specifically, I think there are Four Big Reasons why this is so:

Reason #1: Rugg’s History Doesn’t Work

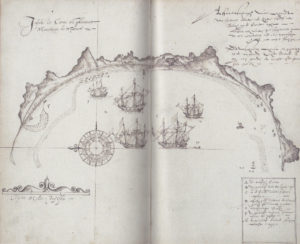

Given that nobody used a Cardan grille before Girolamo Cardano (1501-1576) invented it in 1550, Rugg’s requirement that his putative Voynich hoaxer’s “low-technology” mechanism uses a sophisticated Cardan grille variant necessitates a post-1550 date.

But opposing that is (a) the radiocarbon dating of the vellum to the first half of the 15th century, (b) the mid-15th century ‘humanistic’ handwriting that is used on every page, (c) the 15th century handwriting used for the quire numbers, (d) the 15th century handwriting used for the back page, and (e) numerous Art History arguments pointing to a 15th century origin (which I get bored of reprising, and of defending against Diane O’Donovan’s endless sniping).

So, to shore up his wonky historical timeline, Rugg has to start by saying that the Voynich Manuscript is not only a hoax, but also an extraordinarily sophisticated late-16th century literary forgery, where all these distinctive 15th century features were codicologically layered on top of one another (and using century-old vellum) in order that the finished hoax artefact resemble some unknown kind of 15th century herbal manuscript.

In 2004, we already knew enough to say that this made no sense and was manifestly wrong (I certainly did so, even if nobody else did): but by 2016, this side of Rugg’s claim alone shouldn’t stand up for even a New York second.

So… does his 2016 paper fix this problem in any obvious way? No, sorry, it doesn’t. (Italian playing cards, really? I don’t think so.)

Reason #2: Digital Mimicry Is Insufficient

Unlike the recent herds of Bax-inspired historical linguists roaming wild across the arid Voynichese plains, a-hunting for dry tufts of linguistic tumbleweed lodged in the statistical cracks to feed upon, Rugg initially constructed his clever tables ex nihilo: for a long time, he considered the problem of Voynichese as a purely forward construction issue. That is, all he was trying to do was to mimic the statistics of Voynichese: his claim was therefore not that he could reproduce Voynichese, but that his tables and grilles could produce something that resembled Voynichese (if you didn’t look too closely).

This was, of course, an extremely lame ta-da to be passing off as any kind of über-theory. And so, after a great deal of prodding, he then went on to claim that it should be possible to work backwards from the Voynich Manuscript to try to reconstruct the tables that were used locally. But – to the best of my knowledge – he has retrofitted not even a single paragraph’s worth of tables and grilles in all those years, let alone an entire bookful. (It turns out that Voynichese is much less regular and well-formed than it at first looks.)

Rugg then back-pedalled once again, saying that all he was trying to do was to prove the possibility that a mechanism along these lines could conceivably have been used to generate the Voynich Manuscript.

Yes, and the Voynich Manuscript could conceivably have been found in the middle of a giant golden egg, laid by a space turkey on the Pope’s lap. “Conceivability” isn’t a particularly useful metric, let’s say.

Reason #3: Rugg’s Computer Science Doesn’t Work

At its core, Rugg’s idea of using tables to generate the ghostly immanence of historical signal is a kind of anachronistic computer game hack (and I speak as someone who wrote computer games for 20 years). Beyond the comforting surroundings of his basic word-model, he adapts each and every exception case (and Voynichese has plenty of these: paragraph-initial, line-initial, line-final, A, B, Pharma-A, Bio-B, labelese, etc) with layer upon layer of yet further improvised explanatory hacks.

But even if you – somewhat trustingly – accept that these multi-layered CompSci hacks will collectively coordinate with each other to do the overall job Rugg claims they will, they still all fall foul of the basic problem: that prior to computers, nobody used tables to generate text in such a futilely complicated manner.

Don’t get me wrong, using tables to simulate cleverness is a great hack (and Rugg understands completely that a Cardan grille is nothing more than an indirection method for selecting a subset of a two-dimensional table), and one that sat at the heart of countless late-1980s and 1990s computer games (the Bitmap Brothers were particular masters of this art).

But it’s at heart a great modern hack, not a 16th, 17th, 18th, or even 19th century hack.

Reason #4: Rugg’s Arguments Don’t Work

Even though the preceding three reasons are each gnarly enough to throw their own Herculean spanner into Rugg’s works, this fourth reason is about a problem with the entire structure of his argument.

Rugg claims that his solution of Voynich Manuscript verifies his “Verifier Method”, the approach he claimed to have used to crack it (and on top of which he has built his career). But all he has actually proved is his ability to retrofit a single bad solution to it that is, though not historically or practically credible, conceivably true. This is, in other words, an extraordinarily weak conclusion to be drawing from a hugely rich and complicated dataset, comprising not only the Voynichese text but also all the physical evidence and provenance information we have.

I’ll happily admit that he has produced a possible solution to the Voynich Manuscript’s mystery: but this has come at the cost of discarding any vestige of historical or practical likelihood, an aspect which was just about visible in 2004 but which should be glaringly obvious in 2016.

And if that’s what the poster child for his Verifier Method looks like, I shudder to think what the rest of it looks like.