A year back, I was as mystified by the whole story surrounding the letters linked to Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang as anyone else: no matter how hard I tried to fit the various historical jigsaw pieces together, nothing seemed to link up to anything else in any sensible way.

However, six months ago I took a fresh look at it all, and posted here about a new hypothesis that offered the possibility of explaining pretty much everything: my suggestion was that the evidence pointed not to one person but to two people – a pirate and a Missing Corsair.

Since then, how close have I managed to get to the edge of this knowledge?

The Chevalier

I believe that the reason people started referring to Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang as “Chevalier Nageon” in the 1920s is that someone had noticed the following in the third (“BN3”) letter:

“With the benevolence the First Consul showed me after a glorious feat of arms…”

Here, the “First Consul” can only have been Napoleon Bonaparte: and the way that Napoleon rewarded people (after 1802) was by inducting them into the ranks of the Légion d’Honneur. Hence the ‘benevolence’ was surely at least the lowest ‘Chevalier’ rank of the Légion d’Honneur… ergo the letter-writer was a Chevalier. And if the letter-writer was Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang, then he would be “Chevalier Nageon”, Q.E.D.

However, even if (as I hypothesized back in April) we break the long-assumed link between Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang and the BN3 letter, the rest of the chain of logic still seems to be OK: that is, even if Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang wasn’t a Chevalier, the BN3-letter-writer very probably was. As a result, I firmly believe that we should be looking not merely for a Missing Corsair, but rather a Missing Corsair who was at least a Chevalier in the Légion d’Honneur.

Furthermore, I think it extremely likely (95%) that:

* the Missing Corsair’s “Captain Hamon / Harmon” in BN3 was Jacques-Félix-Emmanuel Hamelin

* the Missing Corsair was on Hamelin’s 380-person-strong La Vénus

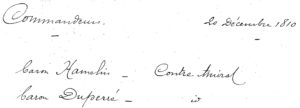

* the Missing Corsair was one of the marine captains and officers entered into the Légion d’Honneur on 20th December 1810

* the Missing Corsair was on one of the parlementaires carrying prisoners of war that arrived back in Morlaix in Spring 1811

But which particular parlementaire do I think he was on?

The Missing Corsair Returns To France

We already know that Hamelin arrived at Morlaix on the Bombay Merchant on 15th February 1811, and that Isaie Alexis de Longueville arrived on the Anna on the 14th April 1811: so we already have two possible ships it could have been

Moreover, I found out a little bit more about Albin Roussin’s journey in an 1887 article called “Les héros de Grand-Port” (in Review des Deux Mondes, 1887, volume 84, pp.101-123). Of course, having dug this up the hard way by trawling through Gallica, I then promptly found a plaintext version of the article in WikiSource. Oh well!

Regardless, this article says (p.113) that Albin Roussin was put on the parlementaire Lord Castlereagh on 11th December 1810, and arrived back in Morlaix on the 19th March 1811. When Roussin was presented to the Emperor (in the following May) in front of a large audience, Napoleon told him: “Je souhaite que vous ayez beaucoup d’imitateurs” (‘I hope that you will have many imitators‘)

So it seems that our Missing Corsair could plausibly have arrived at Morlaix in February 1811, March 1811, or even April 1811: which isn’t very helpful. However, I then found a mention in Biographie des hommes du jour industriels, conseillers-d’État …, Volume 3 that said:

Le capitaine Hamelin, transporté à bord de la Boadicea, fut conduit à Saint-Paul, où il obtint un bâtiment parlementaire sur lequel il s’embarqua avec son état-major et son équipage, et qui les débarqua à l’île de Bas, au mois de février 1811 ; de là le capitaine Hamelin se rendit à Paris, où il fut présenté à l’empereur, qui le félicita publiquement sur sa belle conduite à l’Ile de France.

…which I (freely) translate as…

Captain Hamelin, having been taken on board HMS Boadicea, was then taken to Saint-Paul [in Réunion], where he and his staff and crew were placed onto a neutral boat, from which he subsequently disembarked at the Île de Batz [near Morlaix] in February 1811. From there, Captain Hamelin went on to Paris, where he was presented to the Emperor, who publicly congratulated him on his exemplary conduct in the Ile de France.

Hence I think it highly likely that the Missing Corsair returned to France on the same boat on which his commander Captain Hamelin travelled back (i.e. the Bombay Merchant), and hence arrived at Morlaix on or just before the 15th February 1811.

A Spider In A Hole

Even though Captain Hamelin was taken on board HMS Boadicea, there were two other British ships specifically involved in the action against Hamelin’s La Vénus in September 1810: the Otter and the Staunch. (The Windham was also not too far away in Ile de Bourbon, but this was an East Indiaman rather than a frigate or a brig).

Hence I grabbed an hour in the National Archives in Kew this morning to look at the Captain’s Logs for these three ships: the Boadicea (ADM 51/2176), the Otter (ADM 51/2622), and the Staunch (ADM 52/4619). Unfortunately, even though all three logs did indeed gave an account of the specific day in question, there was nothing like a prisoner list or list of captured officers in any of them which we might cross-reference against the Légion d’Honneur records. Which is a shame, but it is what it is.

All in all, as far as historical archives go, I can do no better than pass on the Italian aphorism that Sergio Toresella once told me (freely translated): though I’ve crawled into dark holes many times, I’ve never yet caught a spider there.

So how do I plan to catch this particular elusive spider?

What About The Bombay’s Records?

Even though I’ve already contacted the French marine archives about the Morlaix prisoner of war list for the Bombay Merchant, I’m not honestly expecting a quick response: I guess it’s more likely to be a document I’d physically need to go to Brest to find myself.

But in the meantime, all is not lost, insofar as there are still a few more things I can check a little closer to home first.

The next set of historical resources I plan to go through is in the British Library. Oddly, the most effective way to find stuff held there to do with the East India Company is to use the National Archives’ Discovery document search engine, which covers the holdings of numerous UK archives. Doing this has revealed a whole load of files held there that might just answer the question:

* IOR/G/9/2 – ff. 152-236, 239-254, 393-409, 492-495, 506-507

* IOR/G/9/7 – ff. 138-144, 145-146, 183-188

* IOR/G/9/11 – ff. 84-169, 170-185

* IOR/G/9/25 – ff. 108-115

* IOR/H/701 – (covers the capture of Mauritius, just for the sake of completeness)

But I suspect the most intriguing set of documents at the British Library may turn out to be L/MAR/B/48 – “journals, ledgers, pay books, imprest books and absence books” relating to the “Bombay” East Indiaman.

Currently, it seems probable to me that the Bombay (Merchant) was the same ship sailed by Captain Archibald Hamilton (1778-1848), and about which the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich has plenty of papers (HMN/60 through to HMN/70 and beyond).

Really, though, the bigger question with all this would seem to be: how close to knowing something do you have to be to actually know it? It feels as though I’m steering my research ship as close to the edge of what we know as can be sensibly maintained – I’m hunting a person for whom I have only indirect evidence, based on a set of letters that itself sits right on the limit of what can be worked with at all.

But perhaps all that is needed now is a single piece of external evidence and this whole wave-function collapses into a single fact, a single name to really go to town on. Wouldn’t that be nice, eh?