Long-suffering Cipher Mysteries readers will no doubt recall various recent posts here about the Hollow River Cipher. Though I had a lot of fun decrypting the word “TREASURE” (that’s something that’s not going to happen to many cipher people, let’s face it), it then turned out that I wasn’t actually the first person to decrypt it. Furthermore, it may well be that some (or indeed all) of the stories around the cryptogram are concocted faux histories.

However, much as with the Beale Ciphers, even if I happen to heartily distrust all the nonsense layered on top of it, I don’t (yet) see any reason to doubt the cipher itself.

Anyway, there’s a particularly interesting word in the plaintext that needs a bit of context in order that it can be understood properly: NAUFRAGE.

Île Saint-Jean – 17th Century

For the Mi’kmaq people, the island was Epekwitk, “Cradle on the waves”. The first Europeans to the island were the French (Cartier briefly visited it in 1534): though Champlain mentioned it in 1603, it didn’t appear on his 1604 map. Even in Champlain’s 1612 map it was little more than a speck, but by the time of his 1632 map it was the proper size, shape and named “l’Ile Saint-Jean”. In HHGTTG terms, “Mostly Harmless”, one might say. 😉

Through the 17th Century, the island was owned (among a number of others) by Nicolas Denys, “La Grande Barbe”, who was a famous entrepreneur and merchant-industrialist. However, his interest was more in fishing rather than establishing any kind of colony. All the same, Denys was more than a little put out when in 1663, Sieur François Doublet was given the island, in return for paying an annual rent to la Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France. However, when Doublet died not long after, his plans to colonise the island fell to pieces. A similar attempt (by Gabriel Gautier) to establish a fishing presence on the island in 1686 also came to naught, despite several expensive attempts.

Île Saint-Jean – 1700-1763

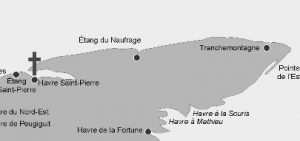

The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 left the island as a French possession, but attempts to colonize it failed, according to Thomas Caulfield in a letter of 16th May 1716. However, the first reasonably successful colonization began around 1719, when a group of settlers were shipwrecked on the North-East coast, at a place subsequently called “Naufrage” (‘shipwreck’). A 1721 letter by De la Ronde mentioned twenty families settled at port Lajoie, and ten more at Tranchemontagne (South Lake), Saint-Pierre (St Peter’s) and Tracadie.

From that starting point, the population of Île Saint-Jean grew as the century proceeded. However, both the British and French forces were fighting for control over the wider area. Following the Siege of Louisburg (1745) [Louisburg was the main town of Île Royal, Cape Breton Island] by New Englander forces, the population of Île Royal was forcibly deported to Europe, though the settlers on Île Saint-Jean (now called Saint John’s Island) was left in place.

But with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, both Île Royal and Île Saint-Jean were returned to the French, in return for Madras and France’s withdrawal from the Low Countries. Claude-Élisabeth Denys de Bonaventure returned to Île Saint-Jean in 1749 with a thousand new settlers, all hoping for a fresh start.

However, 1749 was when Father Le Loutre’s War began: this was a long process whereby the British governors of Canadian provinces would make life progressively closer to intolerable for French settlers. This led to a steady flow of disenchanted settlers moving from the mainland to the safer haven of Île Saint-Jean. This process then peaked in 1755, with mass expulsions of Acadian settlers, many of whom ended up on Île Saint-Jean as well.

The end-game arrived in 1758, when Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew Rollo (the 5th Lord Rollo, aristocracy trivia fans) was sent with 500 troops to secure the island, and to then deport everyone on it to Europe. About 1200 of these deportees died aboard those transport ships: it was a miserable end to what had become a horrible era.

In 1763, the island – now firmly under British control – had its name changed to Prince Edward Island, which is what it has stayed ever since. (Though personally, I have a bit of a soft spot for Epekwitk.)

Naufrage, Revisited

If we go back to the Hollow River Cipher, the date at the top places it firmly at the time of the main French colonization, when the island was Île Saint-Jean:

F R E N C H S L O O P L ['] A I [G] L E [= Most likely plaintext]

G U L F S T L A W R E N [C] E M A Y 10, 1738

The cipher author also tells us the specific place he’s interested in:

L E A G U E W E S T N A U F R A G E

From what we now know, ‘naufrage’ isn’t (as I first thought) a shipwreck, but is actually the place Naufrage (i.e. named after the 1719 shipwreck).

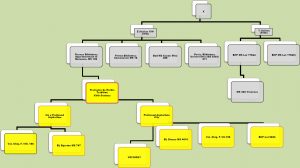

Naufrage is mentioned in a 1752 census, which was turned into a map for a 2008 exhibition at the Acadian Museum (online here):

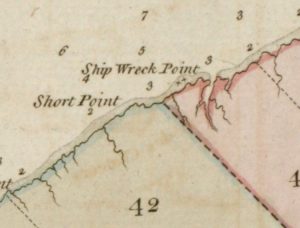

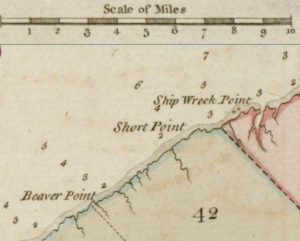

The same name persisted (Anglicized as “Ship Wreck Point”) in a 1775 map:

Perhaps most interestingly, Étang du Naufrage is mentioned in a 1760 book by Thomas Pichon with a horrendously long title, which describes a picturesque 1752 journey around Île Saint-Jean that the author had taken:

Nous continuâmes notre route en côtoyant la mer pendant six lieues jusqu’à l’étang du naufrage. Cette côte, quoi qu’assés unie, ne presente à la vûe que desert où le feu a passé, et plus avant les terres sont couvertes de bois franc. Un seul habitant que nous trouvâmes, nous assura que les terres des environs de l’êtang sont très bonnes, aisées à cultiver, et que tout y vient en abondance. Il nous en donna une preuve qui nous fit plaisir, c’étoit le peu de froment qu’il avoit eu la faculté de semer cette année là; effectivement rien n’étoit fi beau que ses épics qui étoient plus gros, plus longs et mieux garnis que ceux d’Europe.

Ce fut à l’occasion d’un naufrage qu’un batiment François fit sur cette côte, qu’on a donné à l’étang le nom d’Etang du naufrage. Quelques passagers, après que le vaisseau se fut perdu à quatre lieues en mer, se sauverent sur des débris et furent les premiers qui s’établirent au havre Saint Pierre. Au reste l’étang s’enfonce un quart de lieue dans les terres au sud-ouest. Sa largeur à son extremité est d’une portée de canon de quatre livres de balle. Il s’y décharge un grand ruisseau qui ne tarit jamais, parce qu’il est entretenu par deux sources qu’on trouve à deux lieues et demie dans les terres d’ouest sud-ouest. Ce ruisseau peut fournir assés d’eau, presqu’en tous tems et malgré les gelées à plusieurs moulins qu’on y a construit.

La côte depuis le havre de la fortune jusqu’à celui de Saint Pierre où nous arrivâmes le 14 Aoust après avoir encore côtoyé pendant six lieues depuis l’étang, […]

Translated roughly (by me, so expect fluency rather than accuracy):

We continued on our journey, coasting six more leagues around the island to the étang du naufrage. This place […] looked like the empty space you get after fire has cleared it, and beyond that the lands are covered with hardwood. One inhabitant whom we found assured us that the lands around the étang are very good, easy to cultivate, and that everything is in abundance. As proof, he showed us a little wheat he had been able to sow that year; indeed, nothing was as beautiful as its ears, which were larger, longer, and better than those of Europe.

It was on the occasion of a French shipwreck on this coast that the étang was given the name of étang du naufrage. Some passengers who had clung to the debris after their ship had been lost four leagues out to sea, ended up becoming the first settlers at St. Peter’s Harbour. The étang itself extends a quarter of a league into the lands to the southwest. At its widest, its width is the range of a four pound cannonball. A large brook discharges into there: this never runs dry because it is maintained by two springs, which are found two and a half leagues west-southwest. This brook provides a water supply to several mills that were built there, almost at all times and despite the frosts.

The coast from le havre de la fortune to that of St. Peter where we arrived on 14 August after having travelled for six leagues from the étang, […]

“League West Naufrage”…

So: now that we know exactly where Naufrage is, we also know that the cipher author is directing us to go one league west from there. But… how far is a league?

This is, of course, one of those niggly questions that gets historians sighing heavily, because different people at different times and different places had different answers.

For an Englishman of the 18th Century, a league on land was three miles, while a league at sea was three nautical miles (~3.4 miles). But I have to also point out that our cipher author was on a French ship, and a French league (lieue de Paris) was standardized in 1674 as 2000 toises (~2.4 miles), and then in 1737 (the year before the cipher’s date) as 2200 toises (~2.66 miles).

Yet even the yardstick (leaguestick?) we have in Pichon’s account – that it is six (presumably French?) leagues from Naufrage to Saint Peter’s Bay, which is about 24 miles / 36 kilometers by sea (because you have to double back on yourself) – isn’t much help, because it would give a figure of 4 miles per league. So unless the geography around Saint Peter’s Bay has changed much in the last couple of centuries, Pichon’s ability to estimate distances in leagues seems to have not been as good as he imagined.

Adding all these classes of inaccuracy together, it seems likely to me that the least and most ‘one league’ could be in practice are about 2 miles and 4.5 miles respectively. So: how does this stack up with the (now widely presumed) identification of the same location with the Hollow River?

The location given for Hollow River by the local government is 46°28’00.0″N 62°30’00.0″W . According to Google Maps, this runs alongside the modern Swallow Point Road, and its mouth is about 6.8km (4.2 miles) from the mouth of the Naufrage étang. So Hollow River would seem at first to be a reasonable guess.

If we look at MapCarta’s Hollow River page, we can see two modern candidate rivers – Hollow River and Fox River, which I’ve highlighted here in red and blue respectively:

Now, remembering that the cipher says…

ONE HUNDRED AND ELEVEN YDS UP SMALL STREAM

…which is this small stream to be, Hollow River (6.8 km along from Naufrage) or Fox River (5.6km along)? I have to say that Fox River, if it was around in 1738, would seem to be a better candidate than Hollow River. And there’s even Cow River, which is a mere 2.2km along from Naufrage. So let’s look more closely at the 1775 map:

Here, we can see a decent-sized stream heading South from just below the ‘n’ of “Short Point”, marked as being ~3.5 miles (5.6km) from the mouth of the Naufrage étang, which I think lines up exactly with the modern Fox River. The next reasonable size stream along would seem to be the slightly smaller-looking stream to the right of “Beaver Point”, but this would seem to be about 5.5 miles (8.8km).

So it would seem from this historical detective work (a) that Hollow River didn’t even properly exist in 1775, (b) that calling it the Hollow River Cipher may well have been based on a misidentification from a century ago, and (c) that the stream we should be actually interested in is the modern Fox River, which appears to be the first reasonable size stream about a league west of Naufrage on the 1775 map.

“ONE HUNDRED AND ELEVEN YARDS”?

At this point I should add that 111 yards is pretty close to 50 toises (French fathoms, i.e. 2.131 yards x 50 = 106.5 yards), so I’m guessing that the cipher author heard the French sailors talking about going “cinquante toises” down the “petit ruisseau”.

Where would 111 yards down the Fox River take us? If we have a look in Google Maps, the satellite image shows us where (I’m pretty sure) the Fox River is (the first white dot down marks 100m or so from the end, which is pretty close to 50 toises):

The rest you can figure out, I’m sure. 🙂

Finally: why take treasure up a small river, you may ask? The answer would seem to be painfully obvious: that those wanting to conceal it would want to carry it as far inland on a small boat as they easily could.

In that respect, these people would seem to be brothers-in-(yard)arms to Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang (operating at the same time, though in a different ocean entirely), who wrote that he had hauled his treasure up a small creek, also presumably in a small boat. Wouldn’t it be nice if something were still there, in both cases? Not hugely likely, for sure, but a nice thing to dream about all the same.

PS: for more on the history of Île Saint-Jean in French, I found the following two articles (this one and this other one) very helpful indeed.

Update: 1752 Census entry

While looking (unsuccessfully) for decent French maps of the island, I found a nice webpage containing a detailed 1752 census of Île Saint-Jean, The census taker (Sieur de la Roque) travelled round the island on land. (The French original can be found here.) It may well be that he travelled with Thomas Pichon, because they both seem to have had the same conversation with the (unnamed) settler at Naufrage.

At Pointe de l’Est:

Next, after making another two leagues, we doubled Pointe de l’Est. This point had been reduced to a wilderness by a fire which has passed through this section, and the settlers have established themselves at a distance of two leagues from the point on the north side. The land upon which the people have settled is of the best for cultivation. Nevertheless they have sown no seed here, and the truth is that they lack the seed to sow, and if the King does not make them a gift or a loan of seed so that they can sow it next spring they will find it impossible to maintain themselves, being today at the last stage of poverty through the great mortality among their live stock.

He then moved on to Naufrage:

We left on the 13th and took the route for l’Etang du Noffrage,

following the sea shore continually for the six leagues at which the

distance from the Post at Pointe de l’Est to l’Etang du Noffrage is

estimated.

In this distance we met with nothing worthy of notice. The land is a

desert owing to the occurance of the fire, but a short distance inland

the country is covered with hardwood and the soil was good for the

production of all kinds of grain and roots; everything coming up in

abundance. Owing to the lack of seed grain the settler here was unable

to seed his land this year, but the small quantity of wheat which he was

able to sow is amongst the finest in the Island. The ears are long,

large, and well filled. The Etang du Noffrage runs a quarter of a league

inland to the south-west. The breadth averages 80 toises. At the

extremity of the étang, a long brook, which never dries up, discharges

its water. This brook is supplied from two large springs lying at a

distance of two leagues and a half inland to the west-south-west. The

brook contains sufficient water to run flour and saw mills, but as

regards the latter they are considered useless as there is no timber

suitable for sawing, all the hardwood, growing in the surrounding

district being good, at best for the building of boats.

We left on the 14th for St. Pierre du Nord. We counted the distance

between the two points as six leagues by the road. We saw nothing on the

way that calls for a description.

Update #2: Île Saint-Jean Forestry

Anyone who wants a list of sources of pre-1760 writing on Île Saint-Jean would be well advised to look at “Early Descriptions of the Forests of Prince Edward Island: A Source Book” by Douglas Sobey. “Part I: The French Period – 1534-1758” is online here.