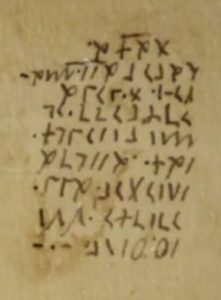

Back in 2006 when I wrote The Curse of the Voynich, I included in the book a whole lot of notes relating to the internal structure of ‘Voynichese’ (i.e. the language, dialect, or manner of writing/encipherment found in the Voynich Manuscript, whichever you happen to feel easiest which).

To be clear, I didn’t claim to have deciphered so much as a single letter: rather, I wanted to communicate the high-level view of Voynichese I had built up (not too far from that of Brigadier John Tiltman) as a collection of smaller ciphers, all artfully arranged into an elegant overall system.

The mystery of EVA d and EVA y

For example, I believed (and in fact still do believe, and for a whole constellation of reasons) that EVA -d- (word-middle) and EVA -y (word-final) are probably kinds of scribal abbreviations (e.g. contraction and truncation respectively): and that to successfully read Voynichese, we will ultimately need to reconstruct how its words are abbreviated.

At the same time, I believe that EVA d- and EVA -y (both word-initial) work differently again, i.e. that the same two letter-shapes are doing ‘double duty’, that they mean different things when placed in different parts of a word.

In Latin, the shorthand shape ‘9’ (the same as EVA y) behaves very similarly to this, insofar as it stands in for com-/con- when it appears word-initially, and for -us when it appears word-finally. This was still in (admittedly light) use in the mid-fifteenth century, so the idea that something could mean different things in different positions within words was still ‘in the air’, so to speak.

Really, what I was trying to do was understand how the Voynichese ‘engine’ worked: to not only identify the individual cogs and pinions (i.e. Tiltman’s smaller component ciphers) but to also move towards identifying how these meshed together to form not just a collection of adjacent tricks, but a coherent (if subtly overlapping) system.

The overall metaphor that seemed most productive to me was that of architecture: that the components that made up Voynichese were laid out not haphazardly, but had a kind of consistent conceptual organization to them, yielding what appeared to be rigid use-structures and language-like rules.

Yet at the same time, attempts to produce formal Voynichese grammars to capture these have proved unfruitful: even though thousands of statistical experiments seem to back up the overwhelming intuition that there’s something there if we could only see it, we remain blind to exactly what is going on.

Yes, It’s Unpigeonholeable

Some Voynich linguists try to argue against my view by claiming that I’m describing it purely as a cipher, which (in their view) ‘of course’ it simply isn’t. But the problem is that that’s really not my position at all.

Rather, one of my overall beliefs about Voynichese is that the person who constructed it would have been able to almost entirely (though perhaps not necessarily 100% completely) read it back off the page. And so a lot of what I’m talking about isn’t so much cryptography as steganography, “hiding in plain sight”: and that in turn isn’t so very far from being a linguistic problem.

So if (as I suspect) Voynichese turns out to be equal parts cryptography, steganography, shorthand and language, decoding it will require a significant collaborative effort: but it will also require people to stop trying to pigeonhole it into a single category. Is there any real likelihood it is pure language, or pure shorthand, or pure steganography? For me, the answer is no.

What many of us moderns forget is that the Renaissance (and particularly the fifteenth century) was a time long before the borders between intellectual specializations had started to be so anxiously patrolled. Back then, there was no hard line between language and cipher, between fact and fiction, between Arts and Sciences, even between past and present: thinking was far muddier, and far less clearly defined. Or, if you want to be charitable, much more fluid and creative. 🙂

And so I think we really shouldn’t be surprised if the creator of the Voynich manuscript trampled gleefully over the flower beds of what we now think of as convention: it would be several hundred years before intellectual “Keep Off The Grass” signs would start to appear.

Vowels, Consonants, Numbers, And, The

Regardless of all the above, I think that anyone trying to make sense of Voynichese really has to start with the most basic questions. Surely the biggest ones (and these have bugged me for nearly twenty years) are the classic questions of both cryptologists and linguists alike:

- Where are the vowels?

- Where are the consonants?

- Where are the numbers?

- Where are the ‘and‘ words?

- Where are the ‘the‘ words?

Unfortunately, many people who go hunting for vowels in Voynichese take its letter shapes completely at face value: and by that token, EVA a / i / o would ‘surely’ be standing in for (plaintext) A / I / O. Even though this at first seems to move you forward, what immediately happens next is that you find yourself utterly, ineffably stuck: that even though “vowel = VOWEL” may (briefly) feel like a plausible starting point, Voynichese doesn’t actually work like that at all.

And so the more well-organized vowel hunters move on to applying linguistic algorithms (such as Sukhotin’s) to determine which letters are vowels, and which are consonants. This normally (e.g. depending on which transcription you are using, how you parse EVA letters into glyphs, etc) will yield much the same kind of result: which also gets you basically nowhere.

This also doesn’t even begin to attempt to answer the question of where the numbers are (for in a manuscript that size, there must surely be numbers aplenty in there, right?); where the ‘and‘ words are hiding; and just as much where all the ‘the‘ definite articles are to be found.

Honestly, how is it that researchers can collectively invest so much time staring at Voynichese and yet they almost all never try to formulate answers (however hypothetical or speculative) to such basic questions?

Shape Families

Despite our continuing inability to read Voynichese, I think we can identify – purely from their shapes and the similar ways they appear – a number of distinct groups of letters:

- EVA e, ee, eee, ch, sh (the ‘c-family’)

- EVA t, k, f, p (the ‘gallows family’)

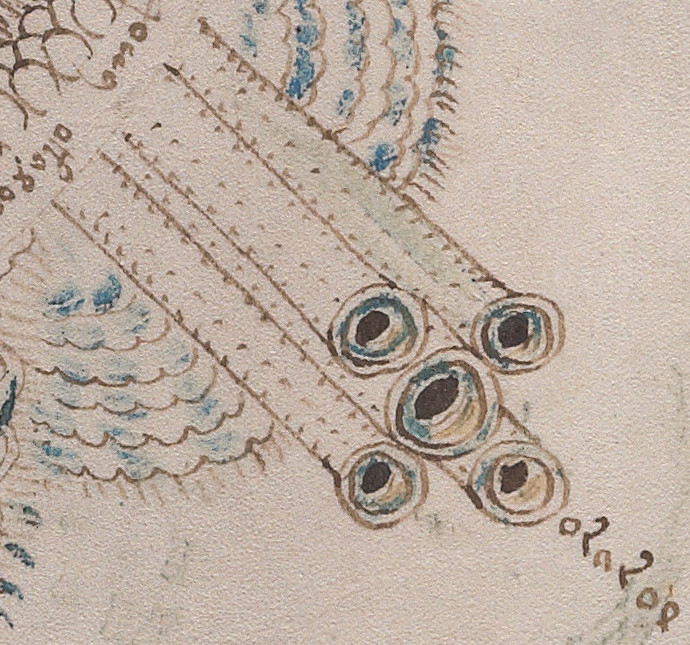

- EVA or, ar, ol, al

- EVA an, ain, aiin, aiiin

- EVA air, air, am, aim

- EVA d, y

- EVA qo

- EVA s

Oddly, many of the shapes inside each of these groups can often be substituted for one another (e.g. gallows can normally be substituted one for the other to form similar words): and this alone forms a kind of skeletal “shape-grammar” for Voynichese. (Though quite why this should be the case remains a mystery.)

One of the things I have long wondered about these shape families (which, once again, wasn’t not far at all from what Brigadier Tiltman had suggested) was whether each of them might have previously expressed some kind of individual cipher-like trick: for example, I wondered whether the ololol-like repeats of the or/ar/ol/al group might have originally been specifically used to disguise Roman numbers.

In which case Voynichese wasn’t itself a work of invention so much as one of careful assembly, its creator stitching (and adapting) a set of pre-existing tricks together to form the illusion of a coherent whole.

In which case, the intriguing question then arises as to whether we might be able to reconstruct what each of these families is trying to conceal. Might we be able to work out the secret history of each of these sub-tricks?

On The Vowel Trail

All the same, the question of the day comes down to this: which of these distinct families might be hiding the vowels?

Back when I was writing Curse, I speculated whether the series of ‘c’-like shapes in Voynichese (EVA e, ee, eee, ch, sh) might somehow be standing in for vowels. After all, the members of this set do seem to share some kind of visual ‘family connection’ as far as their shapes go (i.e. they’re all formed of right-facing semicircles, and there are (superficially, at least) as many of them as the number of vowels you might typically expect to find in a typical European text (i.e. five).

A famous medieval monastic cipher also replaced vowels with clusters of dots (e.g. one dot for a, two dots for e, etc), so the idea that a cipher and/or alphabet might ‘thematically obfuscate’ a connected group of letters in the same way is visually (and indeed historically) quite appealing.

At the same time, I think that while this may well prove to be true (or even largely true) for Currier A pages, at the same time something odd is going on with Voynichese Currier B pages that this isn’t capturing. So Voynichese as a whole remains subtler and more awkward than this is able to completely account for.

Strike-Through Gallows

What I also find hugely intriguing is not that there are families of shapes, but that there are also mysterious areas of overlap between those families.

These are the places where I think the creator of Voynichese used his cunning to ‘hybridize’ them, i.e. to adapt the area between a pair of families, to turn the overall set of families into a complete system.

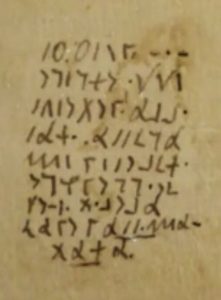

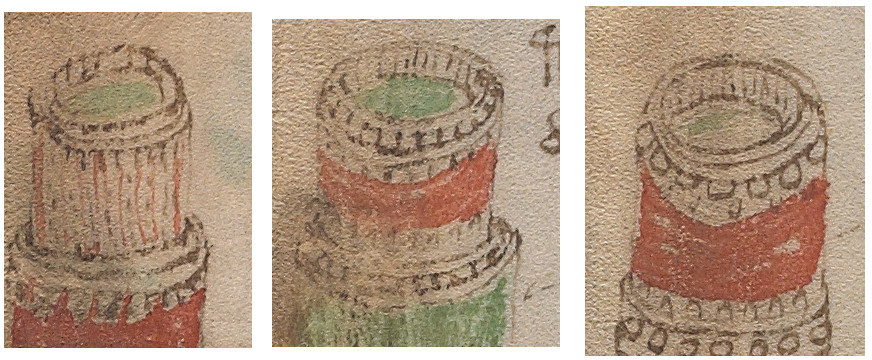

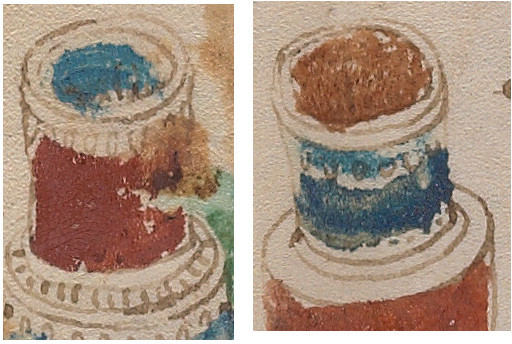

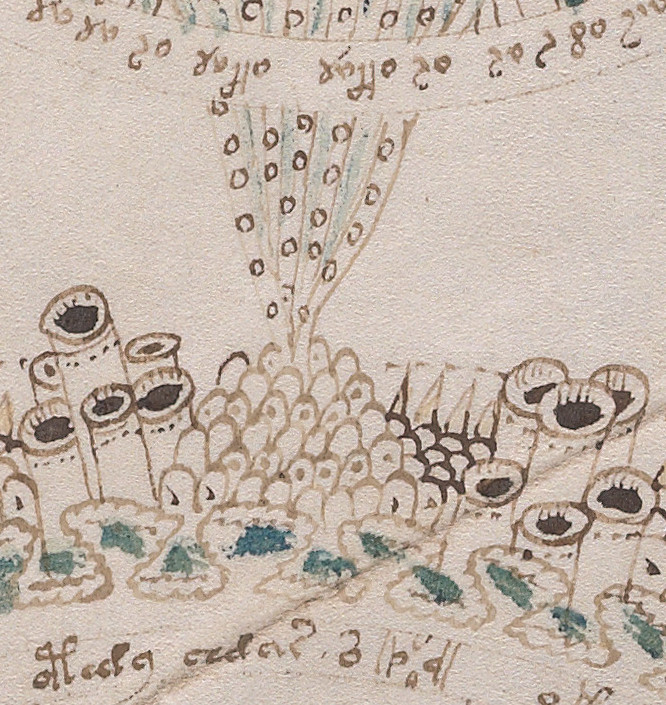

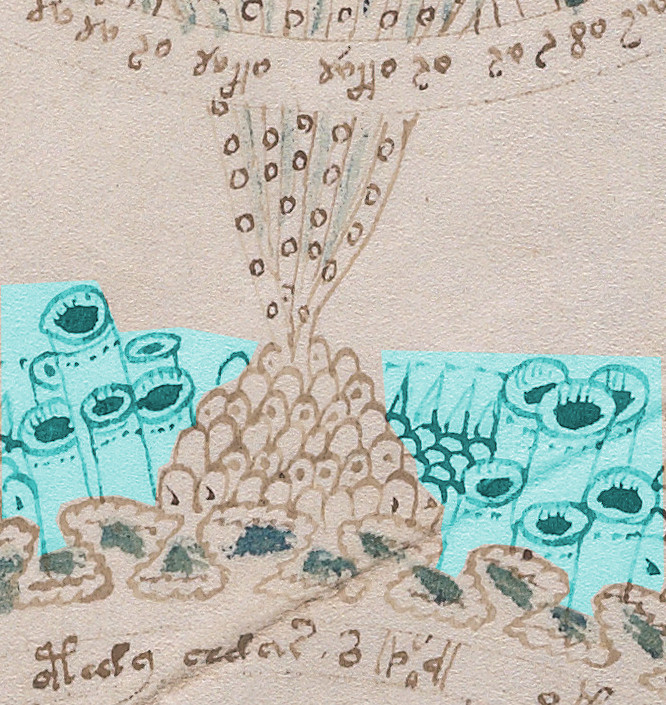

Nowhere is this kind of overlapping clearer than with the strike-through gallows. These are instances where shapes in the gallows family (EVA t, k, f, p) are kind of ‘struck-through’ by a ‘ch’ shape. The difficulty of rendering these struck-through gallows as text led to a lot of debate between people proposing various Voynich transcription alphabets.

In the end, the EVA transcription rendered the ‘ch’ shape as two half-letters so that struck-through gallows could be rendered with a ‘c’ and an ‘h’ either side of it, e.g. EVA k -> ckh, t -> cth, f -> cfh, p -> cph. But remember that this is no more a handy transcription convention, and really shouldn’t be interpreted as endorsing any particular view of what is actually going on ‘under the hood’.

Because that’s another big question researchers have been all too content to avoid ever since EVA arrived: in short, what on earth is going on with these struck-through gallows?

Back when I wrote Curse, I pointed to a 1455 Milanese cipher where, very unusually, ‘subscriptio’ was rendered in a very similar strike-through way: and so proposed that this might well be what we are looking at with strike-through gallows. While this made good hypothetical sense at the time, I have to say it also didn’t really sit well with the idea that EVA ‘ch’ might be in some way part of a vowel family. And so I was left not seeing how these two families and their overlap might have been meshed together

But a couple of years ago, I had an idea as to how all these different pieces could have been reconciled into a single system…

Cicco Simonetta and Q

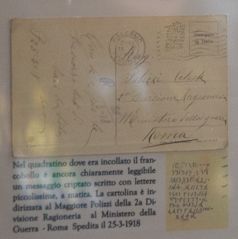

Philip Neal’s exemplary translation of Cicco Simonetta’s 1474 Regule (‘rules’) for codebreaking includes his translation of Simonetta’s notes on the weakness of the letter ‘Q’:

Consider if in the published writing there be any cipher which always and everywhere is followed on by one and the same cipher, for such a cipher is representative of q, and the other following is representative of u, for always after q follows u, and the cipher which follows on the cipher representative of u is a vowel always, for always after q follows u and another vowel follows after u.

What, then, are codemakers to do to avoid people using QU as a giveaway? Apart from adding in nulls, Simonetta suggests possibly “putting one sole letter in place of q and u”.

Now, what I found interesting about this is that in 1474 (actually, I strongly suspect that Simonetta was copying out a document that had been compiled some twenty years previously, so perhaps in 1454 or so), Milanese codebreakers were aware that leaving ‘q’ and ‘u’ adjacent was a crypto ‘tell’, that could be used to break their ciphers.

And yet in the Voynich Manuscript, there was apparently no sign of any mechanism or shape family being used to obfuscate a ‘qu’ pair. Or… was there?

Revisiting EVA ch

And so I finish this with the thought that struck me a couple of years ago. What if the strike-through gallows were simply formed by a ‘Q’ shape being struck through by a ‘U’ shape?

For if that were the case, we could probably conclude that not only is EVA ‘ch’ a vowel, but the letter it is standing in for is U/V.

Ah, some might say, but there are 18 instances of EVA ‘chch’ in the Voynich Manuscript. However, I would point out that many/all of these could very easily have been copying errors for the (almost microscopically different) EVA ‘chee’ (e.g. ‘dchchy’ could instead have been ‘dcheey’, etc).

Similarly, even though there are 755 instances of EVA ‘chee’ in the VMs, there are only 33 instances of EVA ‘eech’. Perhaps this is representative of words beginning ‘V’+vowel, or of specific diphthongs, I don’t know. There are 4989 ‘che’ instances, but only 180 ‘ech’ instances: maybe this is something that can be mined for more information and insight.

Of course, I don’t know that I’ve got this right: but the suggestion that EVA ‘ch’ is ‘U/V’ is a hypothesis that’s based on good observation and good crypto history, and offers plenty of space to explore and to work with.

For example, it would suggest that ckh is actually the same as (k)(ch), which may help normalize a lot of the text (and please don’t try to argue back to me that k ‘can only’ maps to a single plaintext letter, Voynichese is much too subtle for that, or else we wouldn’t get qokedy qokedy etc).

Lots to think about, anyway.