A recent post on voynich.ninja brought up the subject of differences / similarities between Voynichese words starting with EVA ch and those starting with EVA sh. But this got me thinking more generally about the difference between ch and sh in Voynichese (i.e. in any position), and even more generally about letter contact tables.

Problems With Letter Contact Tables

For ciphertexts where the frequency instance distribution has been flattened, a normal first test is William Friedman’s Index of Coincidence (IoC). This often helps determine the period of the cryptographic means that was used to flatten it (e.g. the length of the cyclic keyword, etc). But this is not the case with the Voynich Manuscript.

For ciphertexts where the frequency instance graph is normal but the letter to letter adjacency has been disrupted, the IoC is one of the tests that can help determine the period of any structured transposition (e.g. picket fence etc) that has been carried out. But the Voynich is also not like this.

So, when cryptologists are faced by a structured ciphertext (i.e. one where the frequency instance graph more closely resembles a natural language, and where the letter adjacency also seems to follow language-like rules, the primary tool they rely on is letter contact tables. These are tables of counts (or percentages) that show how often given letters are followed by other given letters.

But for Voynichese there’s a catch: because in order to build up letter contact tables, you have to first know what the letters of the underlying text are. And whatever they might be, the one thing that they definitely are not is the letters of the EVA transcription.

Problems With EVA

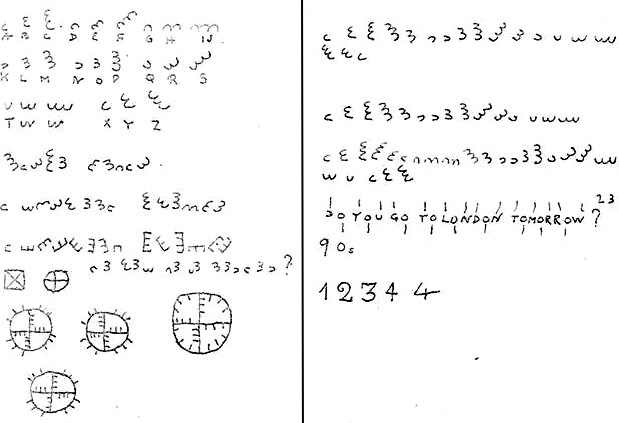

The good thing about EVA was that it was designed to help Voynich researchers collaborate on the problems of Voynichese. This was because it offered a way for them to talk about Voynichese that online was (to a large degree) independent of all their competing theories about what specific combinations of Voynichese shapes or strokes genuinely made up a Voynichese letter. And there were a lot of these theories back then, a lot.

To achieve this, EVA was constructed as a clever hybrid stroke transcription alphabet, one designed to capture in a practical ‘atomic’ (i.e. stroke-oriented) way many of the more troublesome composite letter shapes you find in Voynichese. Examples of these are the four “strikethrough gallows” (EVA ckh / cth / cfh / cph), written as an ornate, tall character (a “gallows character”) but with an odd curly-legged bench character struck through it.

However, the big problem with EVA is arguably that it was too successful. Once researchers had EVA transcriptions to work with, almost all (with a few heroic exceptions) seem to have largely stopped wondering about how the letters fit together, i.e. how to parse Voynichese into tokens.

In fact, we have had a long series of Voynich theorists and analysts who look solely at Voynich ‘words’ written in EVA, because it can seem that you can work with EVA Voynichese words while ignoring the difficult business of having to parse Voynichese. So the presence of EVA transcriptions has allowed many people to write a lot of stuff bracketing out the difficult stuff that motivated the complicated transcription decisions that went into designing EVA in the first place.

As a result, few active Voynich researchers now know (or indeed seem to care much) about how Voynichese should be parsed. This is despite the fact that, thanks to the (I think somewhat less than positive) influence of the late Stephen Bax, the Voynich community now contains many linguists, for whom you might think the issue of parsing would be central.

But it turns out that parsing is typically close to the least of their concerns, in that (following Bax’s example) they typically see linguistic takes and cryptographic takes as mutually exclusive. Which is, of course, practically nonsensical: indeed, many of the best cryptologists were (and are) also linguists. Not least of these was Prescott Currier: I would in fact go so far as to say that everyone else’s analyses of Voynichese have amounted to little more than a series of minor extensions and clarifications to Currier’s deeply insightful 1970s contributions to the study of Voynichese.

Problems With Parsing

Even so, there is a further problem with parsing, one which I tried to foreground in my book “The Curse of the Voynich” (2006). This is because I think there is strong evidence that certain pairs of letters may have been used as verbose cipher pairs, i.e. pairs of glyphs used to encipher a single underlying token. These include EVA qo / ee / or / ar / ol / al / am / an / ain / aiin / aiiin / air / aiir (the jury is out on dy). However, if you follow this reasoning through, this also means that we should be highly suspicious of anywhere else the ‘o’ and ‘a’ glyphs appear, e.g. EVA ot / ok / op / of / eo etc.

If this is even partially correct, then any letter contact tables built on the component glyphs (i.e. the letter-like-shapes that such verbose pairs are made up of) would be analysing not the (real underlying) text but instead what is known as the covertext (i.e. the appearance of the text). As a result, covertext glyph contact tables would hence be almost entirely useless.

So I would say that there is a strong case to be made that almost all Voynichese parsing analyses to date have found themselves entangled by the covertext (i.e. they have been misdirected by steganographic tricks).

All the same, without a parsing scheme we have no letter contact tables: and without letter contact tables we can have no worthwhile cryptology of what is manifestly a structured text. Moreover, arguably the biggest absence in Mary D’Imperio’s “An Elegant Enigma” is the lack of letter contact tables, which I think sent out the wrong kind of message to readers.

Letter Contact Tables: v0.1

Despite this long list of provisos and problems, I still think it is a worthwhile exercise to try to construct letter contact tables for Voynichese: we just have to be extraordinarily wary when we do this, that’s all.

One further reason to be wary is that many of the contact tables are significantly different for Currier A and Currier B pages. So, because I contend that it makes no sense at all to try to build up letter contact pages that merge A and B pages together, I present A and B separately here.

The practical problem is that doing this properly will require a much better set of scripts than I currently have: what I’m presenting here is only a small corner of the dataset (forward contacts for ch and sh), executed very imperfectly (partly by hand). But hopefully it’s a step in the right direction and others will take it as an encouragement to go much further.

Note that I used Takahashi’s transcription, and got a number of unmatched results which I counted as ??? values. These may well be errors in the transcription or errors in my conversion of the transcription to JavaScript (which I did a decade ago). Or indeed just bit-rot in my server, I don’t know.

A ch vs B ch, Forward Contacts

A ch

(cho 1713)

—– of which (chol 531, chor 400, chod 196, chok 130, cho. 113, chot 94, chos 50, chom 28, choi 20, choy 18, chop 14, chof 12, choe 11, choa 7, choc 6, choo 5, cho- 4, chon 4, chog 2, cho??? 69)

(che 918)

—– of which (cheo 380, chey 229, chee 156, chea 64, chek 30, chet 19, ched 12, ches 8, chep 7, cher 2, cheg 1, chef 1, che. 1, che* 1, che??? 7)

(chy 544)

(cha 255)

(ch. 112)

(chk 60)

(chd 35)

(cht 31)

(chs 21)

(chch 5) (chp 5) (chsh 4) (chm 2) (chi 2) (chc 2) (chf 1) (chl 0) (chn 0) (chr 0) (chs 0) (ch- 0) (ch= 0)

B ch

(che 3640)

—– of which (ched 1482, chey 597, cheo 565, chee 537, chek 119, chea 82, ches 55, chet 42, chep 25, chef 15, cher 4, cheg 4, che. 2, chel 1, che??? 117)

(chd 725)

(cho 633)

—– of which (chol 200, chod 123, chor 83, chok 65, chot 44, cho. 34, chop 7, chos 22, choa 10, chop 7, choy 4, choe 4, chof 4, choo 4, choi 2, cho= 1, cho??? 26)

(ch. 403)

(chy 331)

(cha 185)

(chk 84)

(chs 50)

(cht 38)

(chp 20)

(chch 6) (chc 6) (chsh 5) (chf 2) (chi 0) (chm 0) (chl 0) (chn 0) (chr 0) (chs 0) (ch- 0) (ch= 0)

Observations of interest here:

- A:cho = 1713, while B:cho = 633

- A:chol = 531, while B:chol = 200

- A:chor = 397, while B:chor = 83

- A:che = 918, while B:che = 3640

- A:ched = 12, while B:ched = 1482

- A:chedy = 7, while B:chedy = 1193

- A:chd = 35, while B:chd = 725

- A:chdy = 21, while B:chdy = 504

As an aside:

- dy appears 765 times in A, 5574 times in B

A sh vs B sh, Forward Contacts

A sh

(sho 625)

—– of which (shol 174, sho. 143, shor 105, shod 77, shok 32, shot 22, shos 11, shoi 9, shoa 6, shoy 5, shoe 4, shom 4, shop 4, sho- 1, shof 1, shoo 1, sho??? 26)

(she 407)

—– of which (sheo 174, shee 84, shey 81, shea 20, she. 19, shek 12, shes 8, shed 3, shet 2, shep 1, sheq 1, sher 1, she??? 1)

(shy 153)

(sha 58)

(sh. 39)

(shk 13)

(shd 7)

(shch 6)

(sht 5)

(shs 3)

(shsh 1)

(shf 1) (everything else 0)

B sh

(she 1997)

—– of which (shed 734, shee 386, shey 334, sheo 286, shek 78, shea 37, shet 18, shes 15, she. 13, shep 6, shef 5, shec 2, sheg 2, she* 1, shel 1, sher 1, she??? 79)

(sho 284)

—– of which (shol 89, shod 59, shor 43, shok 24, sho. 23, shot 8, shos 8, shoa 5, shoi 5, shoe 3, shof 2, shoo 2, shoy 1, shop 1, sho??? 11)

(shd 161)

(sh. 136)

(shy 104)

(sha 67)

(shk 35)

(sht 13)

(shs 12)

(shch 6)

(shsh 1)

(shf 1) (everything else 0)

Observations of interest here:

- A:sho = 625, while B:sho = 284

- A:shol = 174, while B:shol = 89

- A:shor = 105, while B:shor = 43

- A:she = 406, while B:she = 1997

- A:shed = 3, while B:shed = 734

- A:shedy = 2, while B:shedy = 629

- A:shd = 7, while B:shd = 161

- A:shdy = 3, while B:shdy = 100

Final Thoughts

The above is no more than a brief snapshot of a corner of a much larger dataset. Even here, a good number of the features of this corner have been discussed and debated for decades (some most notably by Prescott Currier).

But given that there is no shortage of EVA ch, sh, e, d in both A and B, why are EVA ched, chd, shed, and shd so sparse in A and so numerous in B?

It’s true that dy appears 7.3x more in B than in A: but even so, the ratios for ched, chedy, shed, shedy, chd, chdy, shd and shdy are even higher (123x, 170x, 244x, 314x, 20x, 24x, 23x, and 33x respectively).

Something to think about…