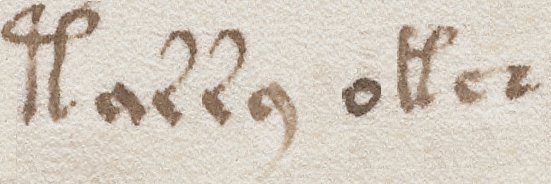

Such a stupid thing for a bright kid to do: pinballing through her mid-teen rebellion, Jena Kyng had wanted to demonstrate some kind of unbranded online tribal allegiance, and ended up with two lines of Voynichese across her lower back (from the end paragraph of page f67r2, as if anyone off-list really cared). Though in many ways, she’d had a lucky escape: imagine ending up with that bozo Gap logo as a tattoo – now that would have really sucked.

But since then, her whole A-grade student train had derailed: and once bad boy boyfriend #1 had morphed into worse boyfriend #2, it was surely just a matter of time before her steadily-growing drink, drugs and abusive partner habits all conspired to help her paint herself into a truly dismal corner of society. All that Voynich research graft lay long behind her: why bother about history when you can see no future?

Countless times since she’d tried to fit herself into straight-ass day jobs, but the minute she got asked to work extra, she’d elevate the royal middle digit… and then it was just a matter of days before the order came from on high to clear her desk. And so, like Michael Palin, Jena’s life now danced defiantly from inhospitable pole to pole – though she somehow doubted Palin could shake his aging Pythonic tush half as as well as her. It’s a skill, she liked to console herself, however minor in the big scheme of things.

So, welcome one and all to her latest home from home, the Green Lizard Club in Muskogee, Oklahoma – ‘Green’ because the owners had replaced all the seedy lighting with LED lamps, thus helping its patrons to feel as though they were saving the planet while stuffing high-denom bills into pole-dancers’ lithely minimalist underwear. Sure, it’s a big fat eco-gimmick: but everybody loves eco-gimmicks, right?

All the same, tonight had been shaping up to be a stultifyingly mediocre night to cap a shockingly shabby week. Jena’s only ray of hope left was the bunch of startup guys – no, not the wind turbine crew (who came in once with some terrified-looking VCs but never returned), but the social media gaggle on Table 3. Bright people, no doubt, but… social media in Muskogee? As if Dave McClure is ever going to drop by here, of all places. Well, not unless he’d absolutely insisted on a live demo from some MIT Star Trek teleportation spin-out. How vividly Daveski would swear if he found himself unexpectedly re-materialized on Okmulgee Avenue, eh?

So, when the lanky one with a testosteronal chin (a bit like a pumped-down Matt Damon) called over to her, she twisted her mouth into her second-best smile (“positive, life-affirming, it’s-great-to-make-money-off-you-geeks”) and danced towards the group. As you’d expect, they knew her name already, but of course she couldn’t give a rat’s ass about theirs. Life is easy when you just don’t care.

“Hey Jena”, Matt Jnr shouted over Hooverphonic’s sweet music, “I think there’s a problem with your tattoo.”

Well, she thought, m-a-y-b-e: but that was when she noticed The Handsome But Odd Guy in the group, mouth slightly open, looking straight through her with his puppy-dumb X-ray eyes. “A problem?” she replied, her PanAm Smile still intact.

“Our guy Rain Man wants to know why you have a Latin poison book for a tattoo”, the tall guy continued. “Oh, and just so you know, Nate’s got Asperger’s, which for him means he codes like an angel but doesn’t like to get out of the office much.”

“No, I’m pretty sure it’s not a poison recipe”, Jena replied turning towards him, a wave of minor cracklets starting to break round the edge of her working smile. “It’s from an astronomical page of…”

“multa michi circa venenorum materiam“, Nate was reading, “dubia occurrent quorum declaratio nixi. Pretty funny tattoo you’ve got there, Miss.”

There was an odd, whooshing sound in her head, as clusters of Jurassic synapses creakily reassembled a fossilized memory from way back when she was still a basically whole person. Yes: it was an incipit she’d seen before, back in her Voynich research life. And if so, then it was probably from Thorndike’s History of Magic & Experimental Science, most likely her favourite Volume IV. So, it would be… the second half of Antonius Guaynerius of Pavia’s twin treatise on plague and poison, composed before 1440. Might Guaynerius have been the Voynich Manuscript’s author? The raw electricity of the possibility surged up and down her, like lightning trying vainly to reach ground. But… even if the idea just happened to be consistent with the radiocarbon dating, nothing that speculative could be true, it was all some spooky coincidence. It had to be, right?

Against her will, Jena was starting to get just a little freaked out. If any of this was even remotely right, the guy Nate must be some kind of idiot savant, unable to tie his shoelaces but able to read the frickin’ Voynich Manuscript. She sneaked a sly glance at his shoes: slip-on Vans. As if I couldn’t guess, she thought. “Does your friend actually know Latin?”, she asked as casually as her quickening pulse would allow.

“Latin?” the lanky guy replied. “He’s always seemed happier talking in Python or C++ than English. But anyway, what is that crazy shit alphabet on your back?”

“Oh, it’s from the Voynich Manuscript, a kind of weird cipher mystery thing”, she said in the best noncommittal voice she could muster. “But I think I’d better show your man the next line down, see if he can read that too.”

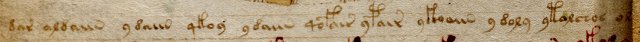

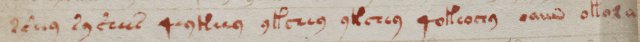

She moved down to the startup guys’ table, and turned to face away from them. Down went the already skimpy silver lamé pole dancing underwear an extra two inches to reveal the only line of red writing in the whole of the VMs. Way back in her Voynich research days, she’d often wondered whether this might be the single line that would some day serve to crack its cipher system. So what would Asperger’s Nate make of it?

“It’s a beautiful thing”, the Odd Guy mumbled. “But I can’t make out the first word, may I move closer, Miss?”

“Uhhh… sure”, she said.

Nate moved right up close, and ran his index finger tenderly over the red letters with a kind of Braille-reading intensity. Instantly, her long-submerged memories of holding the Voynich Manuscript at the Beinecke Library surfaced, and exploded in the physicality of his touch. For that moment, her skin was the Voynich’s vellum, her tattoo was the Voynich’s ink, and she felt utterly entangled in time and space with the Voynich’s author (whoever he or she happened to be).

But… then Jena noticed out the corner of her eye that all the other startup guys were taking out their wallets, placing hundred dollar bills into a pile on the table, and shaking their heads.

“Sorry”, said Nate in a completely different (and totally normal) voice as he stood up, “I can’t make it out, Miss.”

“Hey…”, said Jena as each of the guys high-fived Nate, “what’s going on here?”

One of the group’s regulars, a bald-headed guy with comedy glasses – perhaps the in-house web designer?, she wondered – was laughing into his hand. “Sorry, Jena, it was just a joke. Nate bet us a hundred bucks each he’d get inside your panties tonight, and we all thought he had precisely zero chance.”

“You did this for money?” Jena spat at Nate. “You made a fool of my ass to make yourself some freakin’ money?”

“Oh no”, said Nate handing her the cash, “the money’s for you. These guys work for me, I just enjoyed the challenge. When Larry” – he pointed at the bald-headed guy – “showed me a picture of you on his cameraphone, I thought you looked cute, and – you know – one thing led to another.”

“But all that Antonius Guaynerius stuff”, Jena spluttered, “how on earth did you…”

“Ah, all your old postings to the Voynich mailing list are still online”, Nate smiled. “Didn’t take long to find something to bait the line.”

“You bastard”, Jena said sotto voce, “you… smart bastard” – but this time she could feel her eyes twinkling, for the first time in a couple of years. “You… gonna come back soon?”

“I think I will”, said Nate. “I rather like the view from this table.”

All of a sudden, Jena fancied doing some problem-solving herself.