Here are a couple of items for you that turned up this week. In my (thoroughly unexalted) opinion, I think both demonstrate something I’ve been arguing for years: that trying to infer things about the Voynich Manuscript based in its colours is, sadly, a sure path to madness.

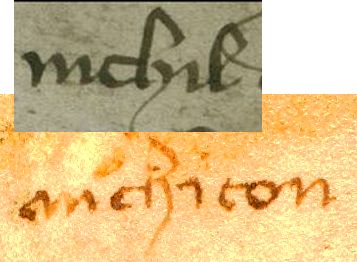

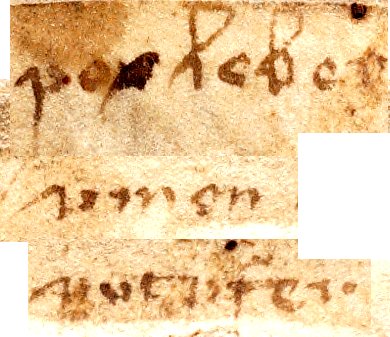

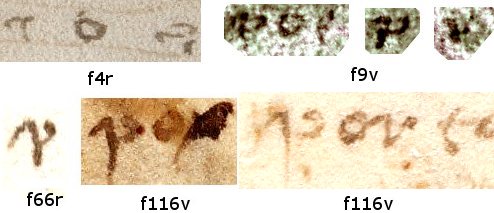

Why? Well, ever since Jorge Stolfi pointed out the disparity between the Voynich’s various paints (in terms both of the range of painting materials used, and of the degree of skill employed) and suggested that a “heavy painter” may have added his/her paint much later (say, a century or more), there has been significant doubt about how much paint the manuscript originally had – really, which paints were (deliberately) original, and which were (speculatively) added later? And given that there is now strong evidence that many of the bifolios and even quires were scrambled several times over the manuscript’s history (apparently by someone with no understanding of the system) and yet nearly all the paint transfers appear to be between pages in their current order, it seems that a great deal of the Voynich Manuscript’s paint was added later on in its life by someone who similarly didn’t understand what it was saying.

It would therefore seem highly likely that the Voynich Manuscript was even more of an “ugly duckling” in its original ‘alpha’ state than Wilfrid Voynich realized – a particularly plain-looking artefact. As a result, I think that trying to reconstruct the mental state or attitude of the author based mainly on the colours used but without an in-depth grasp of the codicology is an approach that surely has ‘big fail’ written all over it.

Yet some aspect of human nature drives people to persist in employing this wobbly methodology. And so my first exhibit, m’lud, is something that popped up on Scribd this week: a 22-page document by Joannes Richter called Red and Blue in the Voynich Manuscript. I can do no better than give a sample quotation:-

The illustrations seem to follow a strange color convention, in which the primary color bright yellow is missing in all flowers. This is an uncommon practice in a manual for herbal flowers, as statistically there should at least be one singular flower colored in a yellowish paint. A missing color yellow (amidst an abundance of red, blue and green) for flowers suggests to consider the idea of a religious document, which had to be encrypted to avoid conflicts with the Church. In the Middle Age the primary color yellow had been used as a traitor’s color and an evil symbol.

Well… given that you already know my views, I needn’t add anything to this at all: I’ll just think my opinion really hard for a couple of seconds for you… … … so there you have it. But all the same, if you want to know more about how this fits into Richter’s research on the ancient androgynous sky-god Dyaeus, I can do no better than refer you to his blog Spelling Thee, U and I. Eerily, this turns out to be an anagram of “Need Pelling Hiatus“, make of that what you will. 🙂

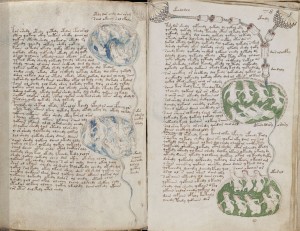

My second exhibit is from Lincoln Taiz (Professor Emeritus in the Department of Molecular, Cellular & Developmental Biology, Sinsheimer Labs, University of California) and Saundra Lee Taiz, whose ideas I first flagged here back in March but who have now published their paper in Chronica Horticulturae, Vol 51, No. 2, 2011. Essentially, despite having countless herbal and pharmacological pages to work with in the Voynich Manuscript, they’ve instead focused their horticultural attention on the ‘balneological’ quire 13, with all its curiously-posed water nymphs and funny coloured pools.

Their working hypothesis is that quire 13 visually expresses the ideas in “De Plantis” by Nicolaus of Damascus, who lived two millennia ago. Ultimately, they somehow infer that in this particular section, the Voynich Manuscript’s “…author depicts a philosophical scene in which women represent vegetative souls located within the very marrow of the plant, driving the processes that make plants grow and reproduce.” Errrr… sorry, but I just don’t think you can build that lofty a tower on top of the use of the colour green in Q13.

And here’s why: if you codicologically reconstruct the original page order of Q13 (as best you can), I’m 99% sure that f84v sat facing f78r in the original gathering order. Here’s what they looked like:-

Here, one set of pools is blue and faded (my guess: original paint), yet the other is green and vivid (my guess: heavy painter, added a century later by someone who had no idea about what the text meant or signified). Yet all the Taizes’ inference chains here are based on the – probably much later – green-coloured pools. As for me, I simply don’t think there’s any significant chance that any historical or horticultural reasoning based on this green colour will have any validity: but feel free to make up your own mind.