The problem with proposing BNF Franc. MS 565 itself as the source of the Voynich Manuscript’s inverted T-O figure is that we know that it stayed put in France (in the Dukes of Bourbon’s library, to be precise) for the whole of the 15th century. And with the Voynich Manuscript, we’re dealing with an object that has genre connections to Northern Italy (herbals, balneo) and Germany (zodiac calendar).

So it is natural to wonder not just about Oresme’s manuscripts being copied (the flow of physically copied letters) but also about Oresme’s reception (the flow of his ideas): which marks the transition from codicology and bibliophily into the realm of Intellectual History. So how did Nicole Oresme’s ideas flow out of France, and where did they end up?

Thorndike Vol IV and Oresme

Aside from chapters on Oresme’s works in Volume III of his History of Magic and Experimental Science, Thorndike often has recourse in his Volume IV to mention Oresme’s reception. For example, on pp.235-6, Thorndike describes the defence of astrology composed by John de Fundis in Bologna in 1451, “which showed that [Oresme]’s attack was still remembered, if not accepted”. Cardinal d’Ailly’s attack on Oresme in 1414 was very much along the same lines.

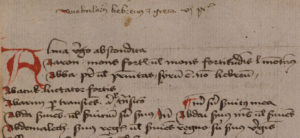

Blasius of Parma (1365–1416), a university professor well known for his interest in French philosophers, commented on Oresme’s work as expressed in a document “De latitudine formarum”, though this was (Thorndike p.73) “probably not by Oresme but a resume by some disciple of his De difformitate or De configuratione qualitatum, compared to which it is a dry compendium”. Interestingly, Giovanni da Fontana (whose enciphered books of machines I have mentioned here numerous times) was a pupil or friend of Blasius: and he “repeats the comparison of the universe to a mechanical clock which God had set running” [p.169], as previously put forward by Oresme. It therefore seems likely that Oresme’s influence on Fontana’s Liber de omnibus rebus naturalibus was via Blasius, rather than directly from his mss.

Moving the clock further forward through the 15th century, Pico della Mirandola referred to Haly (Ali ibn Ridwan, known in the Middle Ages as as Haly Abenrudian]’s commentary on Ptolemy and also to Oresme, who had translated that commentary into French (this is BNF Ms Franc 1348) [p.536], and also to “his precursors at the university of Paris in attacking astrology” [p.539], a list that specifically included Oresme. So I think it reasonably clear that Oresme’s shadow (or at least his anti-astrological shadow) still hung over the 15th century in a number of different ways.

Oresme: “To Infinity, And Beyond”?

Zbigniew Krol’s interesting 2016 paper on Mathematics and God’s Point of View traces practical uses of mathematical infinity back to Nicole Oresme. Krol points out [p.89] that Bernardus Torni of Florence’s In capitulum de motu locali Hentisberi (pulbished 1494) drew directly on Oresme’s work on mathematical infinities. According to Krol, “in the reception and application of Oresme’s ideas, Italy was the main territory which explains why the development of infinite methods emerged exactly there.”

Moreover, “Clagett describes examples of the use of Oresme’s diagrams, e.g. Antonius de Scarparia, Angelus de Fossambruno, Jacopo da Forli; cf. (Clagett 1968), pp. 101–10.” [p.90]. Krol also mentions Oresme’s influence on Paul of Venice (d.1429) [p.92]. Again, Jacopo da Forlì (1364-1414)‘s close connection with Blasius of Parma makes it likely that Blasius was again the middle man in the transmission.

A 1936 paper by (that man again) Lynn Thorndike called Coelestinus’s Summary of Nicolas Oresme on Marvels: A Fifteenth Century Work Printed in the Sixteenth Century Osiris 1 (Jan., 1936) talks about Coelestinus work (which Thorndike dates to 1478), and points out that it seems to derive from Oresme’s Quodlibeta. (Though this is still in France.)

Finally, We Get To Oresme’s Reception

Though the preceding text is more of a random sampling of Oresme’s reception rather than a complete picture (which would take a decade or more to build), I think the overall tendency is already reasonably clear: that to a very large degree, Oresme’s ideas failed to take root in France in the 14th century, and that it would seem to be Italy where they were to gain acceptance during the 15th century (but then only in places).

Having said that, one particular non-Italian strongly influenced by Oresme was his contemporary in Paris Henry of Langenstein (Henry of Hesse the Elder), whom Thorndike discusses in his Chapter XXVIII. All the same, Henry’s influence on the broader history of ideas seems to me to have been fairly minor: I leave it to far better read historians of science to determine the size of that influence. Incidentally, one Henry of Hesse work mentioned briefly by Thorndike at the end of this chapter “seems to have been composed at Paris, since its author states that at Paris from the time that the sun enters Aries until it enters Libra a rainbow cannot appear in the south. These very questions were ascribed to Oresme by Amplonius Ratinck in the catalogue of his library which he drew up in 1412, and the manuscript containing them is still preserved in Erfurt.” [Amplon. F. 380, 14th century]

For me, the key takeaway from all this is simply that for all his rationality, Oresme’s ideas – his infinities, his anti-astrologies, his opinions on the Greats – didn’t comfortably fit the intellectual world around him. Which is not to say he was in any honest sense of the word ‘modern’: his curious-sounding ideas about medicine are often quoted as examples of how non-modern parts of his thinking were. Yet I think it would be a mistake to cast him as an eccentric (whereas he thought very clearly) or as an outsider (whereas he worked at the French Royal Court for many years), as some accounts tend to do. Oresme seemed to think he was right at the centre of the mainstream: the problem was simply that it was at almost all times a one-man mainstream.

As for his reception, the key ‘vector’ via which many of Oresme’s ideas eventually gained currency (and, ultimately, a new intellectual home in Italy) was undoubtedly via Blasius of Parma. For Blasius, once again (and for the last time in this post), Thorndike is a good source: he notes in his 1928 article that “a manuscript of BLASIUS’ commentary on the Sphere of SACROBOSCO calls him ‘Blasius of Parma the Parisian’, and so was perhaps written when he was in Paris.”

I Lied: Here’s Thorndike Again

Reviewing all the above before posting it, I’m again struck by the tension between Thorndike and our “Roger Bacon Manuscript”. It was fine in 1929 for Thorndike to stomp heavily on Newbold’s foolish theory, but why was he so down on what he called “an anonymous manuscript of dubious value”?

That the Voynich Manuscript is a mysterious artefact yet with genuine historical interest is surely a comfortably bland point of view that can be split away from Newbold’s sensationalist (Roger) Baconian theorizing and crazy craquelure microwriting? Yet Thorndike was apparently so horrified by the nonsensical non-thinking around the VMs that the baby in the dirty bath-water never stood a chance.

But as we start – at long last, and long overdue – to collectively mine the scientific manuscripts of the late 14th century and early 15th century, who but Thorndike would you want as your wingman?