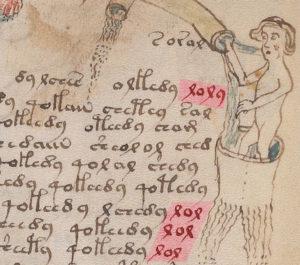

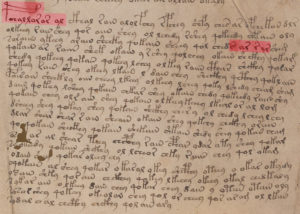

What on earth, you may reasonably ask, is a Voynich “metatheory”? I use the term for a specific kind of Voynich Manuscript theory that seeks to explain more or less all its puzzling features by pointing to a single – usually surprising and/or counterintuitive – lateral step away from what we know (or, rather, what we think we know).

Because of the complexity of the manuscript, ‘normal’ Voynich theories tend to be a patchwork of simple explanations and tangled saving hypotheses (i.e. to try to explain why the simple explanations didn’t actually work): by way of contrast, metatheories instead assert that something really fundamental we tend to take for granted is wrong, and that all our confusions have arisen merely as a result of our treating the manuscript as entirely the wrong category of object.

In short, a theory tries to account for the difficulties we observe fairly directly, while a metatheory tries to explain away more or less the whole constellation of difficulties by pointing to (what it asserts is) a basic flaw in our mindset.

For example, Gordon Rugg’s hoax metatheory asserts that the Voynich Manuscript ‘could be’ or ‘is’ (depending on which journalist he’s talking to) a 16th century hoax (technically, a simulacrum) that was constructed at speed using sets of ingeniously-arranged tables and grilles: and hence that the entire statistical edifice of oddly-language-like textual behaviours that taxes Voynich researchers so greatly is no more than an incidental by-product of the hoax’s cleverly-structured meaninglessness. (It’s just a shame that the radiocarbon date for the manuscript’s vellum turned out to be a century earlier, or else he wouldn’t now look like a bit of a fool. Still, I did tell him so at the time. *sigh*)

Another long-running Voynich Manuscript metatheory is Richard SantaColoma’s 2012 proposal (having previously proposed various similar hoax theories) that Wilfrid Voynich himself created the Voynich Manuscript as a sort of fake or a hoax. Rich continues to write about this, and even gave a presentation called “Is the Voynich Manuscript a Modern Forgery? (And why it matters)” at the recent (2017) Symposium on Cryptologic History in Maryland. Here’s what he looks like:

As always with the Voynich Manuscript, broadly the same thing has been suggested numerous times before, e.g. Michael Barlow’s (1986) Cryptologia article “The Voynich Manuscript – by Voynich?”. But what has distinguished Rich’s presentation is his readiness to fight his corner against all-comers, even though the physical evidence, the historical evidence, the codicological evidence and indeed the palaeographic evidence each separately seems to weigh quite strongly against it. Oh, and the fact that Voynich spent so much time trying to get people to prove it was by Roger Bacon.

Anyway, given that so few people now seem to understand the actual nature of Rich’s hoax claims (and why refuting them matters), I thought a post was a little overdue. So here it is.

Not Probably, But Possibly

As mentioned above, the radiocarbon dating of the vellum points specifically to the early 15th century: to which Rich responds that there is some evidence that some forgers have sometimes used caches of unused old vellum as the support medium for their forgeries. So his argument runs: because some forgers have done this on some occasions, it could have been the case here too. And so the radiocarbon dating – though obviously opposing simple forgeries – cannot be used to absolutely disprove the suggestion that the person who (putatively) hoaxed the Voynich Manuscript.

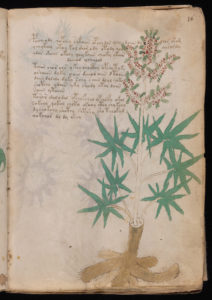

Similarly, even though the codicological evidence directly implies that the Voynich Manuscript has been rebound and overpainted (leaving bifolios mis-coloured and out of context), Rich’s position is that this implies Wilfrid Voynich must have been not just a hoaxer, but a highly sophisticated hoaxer, deliberately shuffling the vellum bifolios and overpainting them to simulate what might have happened over time to such a document (had it been genuine). And, naturally, the more codicological details that you add to this list, the more sophisticated a hoaxer Wilfrid Voynich must surely have been, he would argue. Even though increasing the sophistication and complexity like this makes the hoax less probable, it remains a possibility: and the smaller the possibility, the more wondrous a deception it surely was.

The palaeographic evidence to do with the ultra-rare numbering system used to number the quires is a strange one: this specific (and rather cumbersome and impractical) system seems only to have been used for a few years during the mid-15th century in no more than a few parts of what is now Switzerland. Rich’s response here is that because Wilfrid Voynich was an antiquarian bookseller roaming Europe looking for rare books and manuscripts, he would surely have been well-placed to see such a system in action in the kind of rare manuscripts he regularly saw. Again, even if there is no evidence that Voynich himself actually bought a separate manuscript where this rare numbering system appears, this is a historical possibility that we cannot use to disprove Rich’s basic claim, despite its low intrinsic probability.

Despite the mathematical fact that multiplying two small probabilities together makes a much smaller net probability, Rich’s overall position as far as these contraindicating evidences goes is simply this: that if his proposal that Wilfrid Voynich faked/hoaxes the manuscript is correct, then the final probability that all these other things happened is actually 100%, however unlikely each may seem to an historian.

Some may say that this is a lot like explaining away the chocolate bar missing from the kitchen table as having been taken by hungry aliens who beamed it up to their mothership to eat it: but that’s perhaps a little too glibly sarcastic. Rather, I think the real situation is that Rich defends the possibility that Voynich faked/hoaxed his manuscript so avidly because he thinks that the weight of secondary explanations it yields balances out its net improbability, i.e. that the explanation’s high utility is in inverse proportion to its likelihood.

Document X

In my opinion, however, the place where Rich’s argumental train struggles to stay in contact with its logical rails is in its relationship with a complex of 17th century letters to and from Athanasius Kircher, that famously describe a document strikingly similar to the Voynich Manuscript.

In recent years, this set of letters has been documented and dissected in depth, from which prolonged study there now seems no doubt whatsoever that they are all referring to a single mysterious document (let us call this “Document X“) that was owned by Georg Baresch, passed to Johannes Marcus Marci after Baresch’s death, and then passed by Marci to Athanasius Kircher.

Rich SantaColoma firstly points out that we have no direct proof that Document X is the Voynich Manuscript, and that we should therefore be wary of assuming that the two are the same object. He further contends that in his opinion, the Voynich Manuscript was instead faked/hoaxed by Voynich specifically to make it resemble the description of (the presumably now long-lost) Document X.

For this to be true, it would seem that Wilfrid Voynich must have been aware of the contents of some or all of these letters in 1914 or before, so that he could design his hoax/fake to resemble their description of Document X.

However, even though Kircher’s thick volumes of letters were well-known during his lifetime (e.g. De Sepi’s 1678 description of Kircher’s museum in Rome), they were not listed in later Jesuit sources (such as Sommervogel and De Backer (1893)). Furthermore, the modern rediscovery of Kircher’s correspondence came about long after the Voynich Manuscript appeared on the world stage: until John Fletcher took on the mammoth task of reading and judiciously summarizing the more-than-2000 letters in the 1940s, there had been no more than passing mention of them at all since the 17th century.

For Wilfrid Voynich to have even seen these volumes would therefore have been highly surprising: and what is more, for him to have had sufficient time (and good enough Latin) to work his way through them enough to draw out the strands of the sub-network of letters around the Voynich Manuscript nearly a century before anyone else did is basically impossible.

Apologies to Rich SantaColoma, but there is therefore no way whatsoever that Wilfrid Voynich himself could have built up a description of Document X that would have been good enough to work as a template for him to use when (supposedly) forging/hoaxing the Voynich Manuscript.

Saving Hypotheses Aplenty

If that’s a bust, what other alternatives still remain open? Alas, the problem with imaginative historical interpolation is that there are almost always numerous ways to construct saving hypotheses to paper over the cracks in any wonky explanation’s wall, no matter how wide those cracks may be.

For example, it is possible that an entirely unknown group of people (let’s say, one or more 18th or 19th century Jesuit students) had access to Document X, and from that built up an entirely separate set of descriptions of it: and that it was this separate set of descriptions that Wilfrid Voynich had access to, which he used as the basis for his hoax/fake.

However, the way that the 1665 Marci letter (the one that Voynich said he found tucked into the manuscript) ties in so neatly with the rest of the 17th century Kircher correspondence then becomes very hard to reconcile. And so you would be left with the awkward conclusion that this unknown group of people must also have had access to Marci’s letter. In fact, I think you would be forced to conclude that this letter originally accompanied Document X, but that even though Document X was lost, the still-extant accompanying letter was inserted by Wilfrid Voynich into his faked-up version of Document X.

But this is starting to sound too unlikely even for Rich SantaColoma’s subtle taste for the barely possible. :-/

If you don’t like that, then another possibility could be that Wilfrid Voynich was shown (or saw) Document X itself (including Marci’s letter), but then created his own fake Document X while stealing Marci’s letter to attach to his own version… but this is all veering into the realms of the historically fantastical, and I don’t want to do Rich’s work for him. 😉

And So The Moral Of The Story Is…

In my opinion, what Rich SantaColoma offers up doesn’t really fall in the category of History, but is rather a kind of Debating Society take on historical certainty – for unless you can prove to him to his satisfaction that his argued scenario is impossible by his own criteria, he feels happy to announce that he has won the debate.

Moreover, because Rich seems to believe that the proposal that Wilfrid Voynich himself faked/hoaxed the Voynich Manuscript is itself enough to resolve all otherwise-difficult-to-explain issue, this is something against which he is happy to balance a homeopathically low level of probability, one lower than just about anybody else would consider acceptable.

Yet it seems to me from this that whereas most Voynich theories are based on some kind of psychological projection on the part of the theorist, there is something quite different going on here. Despite the sustained effort Rich has put into sustaining the dwindlingly small possibility side of his Wilfrid-Voynich-hoaxed-it-himself theory, there seems to be a thoroughly irrational component to the other half of his equation. That is to say: what exactly about the Voynich Manuscript would any modern hoax theory throw any light on? What would it explain about the manuscript’s strange text and hard-to-pin-down diagrams? How does the notion that it is a hoax help explain the intricacies of its patterns? If Voynich created it, how did he create it? But all such questions seem to trail off into an awkward silence.

Regardless, all the while Rich’s absolute-disproof-avoiding way of going about this is merely his idiosyncratic opinion, it is (of course) of no wider importance whatsoever: as always, people are free to hold whatever opinions they like, however odd or curious they may be. Given that we’re living in a postmodern world where even Stephen Bax is feted as a Voynich expert, rhyme and reason of the sort I happen to value would seem to be rare commodities indeed: so perhaps I’m simply a Victorian dad peering at Instagram and wondering why all the children depicted aren’t working up chimneys.

But if I were to be asked – as indeed sometimes happens – whether I think there is any merit in Rich’s suggestion of a modern hoax by Wilfrid Voynich, I would have to say: I haven’t seen any sign of it yet, and if I’d have held my breath waiting for it, I’d be long dead by now. Oh well.