Klaus Schmeh, a German encryption professional who over the last couple of years has become increasingly fascinated by the cipher mystery of the Voynich Manuscript, has just been interviewed by the sparky skeptics at Righteous Indignation for their Episode #76 – Klaus’ VMs section runs from 25:50 to 45:45, and gives a fairly pragmatic introduction to the Voynich Manuscript. This was prompted by his Voynich talk at the 14th European Skeptics Conference in Budapest earlier this year (2010).

In fact, it’s quite revealing to see how far he has come from a 2008 German skeptic conference he also talked at (discussed here) [where he fell in behind the mainstream 16th century hoax position] and a 2008 article he wrote (which I reviewed here): it’s nice to see that he’s moved from seeing pretty much everything Voynichese as a combination of pseudoscience and pseudohistory to a rather more nuanced (and realistic) position.

But all the same, looking forward, to where should Voynich skepticism go from here? From what we now know, I’d say there are no obvious grounds for a hardcore skeptical position any more – the vellum seems genuinely old, with the ink freshly written on it, and the radiocarbon dating broadly meshing with the kind of evidence I’ve been working on for the last 5+ years, vis-à-vis:

- The ‘4o’ verbose pair’s brief appearance in various Northern Italian cipher keys 1440-1456 (see The Curse Of The Voynich pp.175-179)

- The parallel hatching which I suspect pretty much forces a post-1440 date if it was made in Italy, or post-1410 if Germany

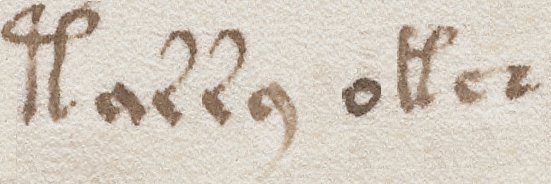

- The two 15th century hands in the marginalia which pretty much force a pre-1500 date for the VMs

- Sergio Toresella’s very specific dating claim, based on his lifetime with herbal manuscripts – that it was made in Northern Italy (probably Milan or the Venice region) around 1460

The swallow-tail merlons on the two castle walls (on the nine-rosette page) that Klaus mentioned in the podcast have actually been debated for at least a decade: although these don’t prove that the Voynich Manuscript was constructed in Northern Italy (where they were an unmissable feature of many castles), they clearly do help to shift the balance of probability that way away from Germany (the #2 candidate region).

And I suppose this is where all this is going: by carefully combining all these pieces together, we can now try to think about the Voynich in terms of probabilities. Even if you discount my Antonio Averlino hypothesis, I don’t honestly mind being what I call “the right kind of wrong” – i.e. looking in the right culture, place, and time, but perhaps finding a false positive to match a very specific forensic profile. Just so you know, I’d currently rate the likelihood of the VMs’s origin’s being Northern Italy at ~80%, Savoy ~10%, Germany ~5%, and anywhere else ~5%.

Hence, if someone were to tell me tomorrow that they’d just uncovered a fifteenth century letter clearly describing the Voynich Manuscript as having been written by Giovanni Fontana, Cicco Simonetta, Brunelleschi, Lorenzo Ghiberti, Leon Battista Alberti, or any one of the hundreds of other desperately clever Northern Italian polymaths who were right there at the birth of the Renaissance, I’d be utterly delighted: for I think that is the cultural milieu linking pretty much all the strands of tangible (as opposed to merely suggestive) evidence to date.

The notions that we know nothing about the VMs and/or that it is somehow destined to be proven a meaningless hoax are not ‘skeptical’ in the true sense of the word: rather, they are postmodernist non-positions, uncritical ‘meh‘s in the face of the interconnected mass of subtle – but nonetheless tangible – historical evidence VMs researchers have carefully accumulated. In the case of the Voynich Manuscript, I think the real “beliefs that are taken for granted by most of the population” at which skeptics should be pointing their weapons of mass deconstruction are not this kind of painstakingly-assembled gear-train, but the widely-disseminated (and utterly fallacious) claim that the VMs is a 16th century hoax for financial gain.

In a way, this would turn Klaus’ own skeptical research chain back on itself – and in so doing would hopefully set him free. “More Schmeh, less meh“, eh? 🙂