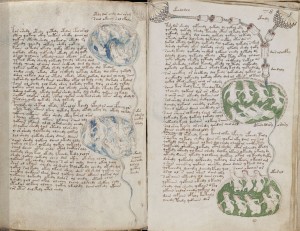

Here’s a particularly interesting Voynich Manuscript paper declassified by the NSA in 2002 (but only recently released as a PDF scan) – so many thanks to the ever-vigilant Moshe Rubin (of Chaocipher Clearing House fame) for pinging me with a link to it, much appreciated! 🙂

Of course, Brigadier John Tiltman’s The Voynich Manuscript – “The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World” is in many ways no more than an introduction to the VMs (and we have far better scans nowadays, so its pages 15..46 need not really concern us): yet all the same, it does contain plenty of incidental meaty morcels for modern Voynichologists to lightly dine upon. For instance:-

- “Newbold’s solution left a legacy of ill-feeling which persisted for many years and which I found reflected in a letter which Charles Singer wrote to me in 1957.“

- Plate 5 [f56r] – “has been identified as some sort of Bindweed (Convulvulus)“

- Plate 6 [f4r] – “seems to me a fairly natural representation of cross-leaved Heath (Erica)“

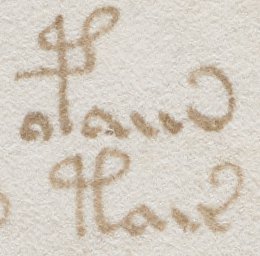

- “All the zodiacal drawings carry the name of the month in the centre in a later hand and in readable script though the language has been disputed.“

- Tiltman was introduced to the VMs in 1950 by William Friedman (which to me reads a bit like a cryptologic version of Cluedo), and started by looking at some of Quire 20’s starred paragraphs.

- “Charles Singer, in a letter to me, put the date at late 16th Century. Professor Panoffsky [sic] and the keeper of the manuscripts at the Cambridge Library both independently insisted on a date within 20 years of 1500 A.D., and the manuscript as we have it may be a copy of a much earlier document.”

- Tiltman discusses Cave Beck’s 1657 universal language at reasonable length (pp.9-10, Plates 21-23), given that Friedman had told him that this was the kind of thing he believed the VMs to be. However, Tiltman was plainly far from convinced.

- In 1957, Tiltman showed photostats of the VMs to various medieval herbal specialists. One of these was Dr. T. A. Sprague in Cheltenham, who – having spent many years on beautiful, well-annotated herbals – found that its “awful pictures” made him “more and more agitated“.

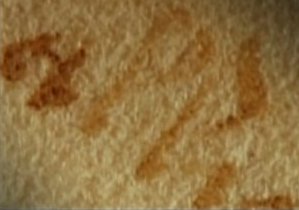

Yet the real substance of the paper arguably lies in the summary of Voynichese’s properties which Tiltman passed back to Friedman in 1951 (remember that Tiltman was arguably the 2oth Century’s greatest non-machine cipher cracker). Tiltman’s own transcription reads Voynichese as being comprised of 17-odd symbols, several of which have second variant forms. The reproduction of Plate 17 is far from crystal clear, but I’m reasonably sure the following is what Tiltman means (converted to EVA), though I’m not 100% sure about “2” because it seems to overlap with “R” and/or “S”:-

Tiltman: D H E G 8 4 O A L S 2 R I C T DZ HZ

EVA: k t l y d q o a n s ? r i e ch ckh cth

2nd variant: f p m sh cfh cph

Though most of the paper is dryly factual (though written in an accessible style), Tiltman managed to sneak his own summary into page 9 – “My analysis revealed to me a cumbersome mixture of different types of substitution.” Of course, this is exactly my conclusion too… but regular Cipher Mysteries readers knew that anyway, so I won’t press the point. 🙂

So, the rest of this post contains Tiltman’s notes (but with the notation converted to EVA), with a few light annotations from me. Note that Peter Long mentioned was a senior figure at GCHQ who corresponded extensively about the VMs (he died in 1999): he’s also mentioned on p.216 of Kennedy and Churchill’s book, though mostly in regard to the “K:D:P” (Kelley/Dee/Pucci) theory of Long’s nephew Tim Mervyn, who has continued his uncle’s Voynichological interest. Enjoy!

* * * * * * * *

(a) Following are some notes on the common behaviour of some of the commonly occurring symbols. I would like to say that there is no statement of opinion below to which I cannot myself find plenty of contradiction. I am convinced that it is useless (as it is certainly discouraging) to take account at this stage of rare combinations of symbols. It is not even in every case possible say what is a single symbol and what is not. For example, I am not completely satisfied that the commonly occurring <a> has not to be resolved into <ci> or possibly <oi>. I have found no punctuation at all.

(b) <ckh/cfh> and <cth/cph>appear to be infixes of <k/f> and <t/p> within <ch>. The variant symbol represented by <m> appears most commonly at the end of a line, rarely elsewhere.

(c) Paragraphs nearly always begin with <k/f> or <t/p>, most commonly in the second variant forms [i.e. <f>/<p>], which also occur frequently in words in the top lines of paragraphs where there is some extra space. [Also known as “Neal Keys”.]

(d) <y> occurs quite frequently as the initial symbol of a line followed immediately by a combination of symbols which seem to be happy without it in any part of a line away from the beginning. Otherwise it occurs chiefly before spaces very frequently preceded immediately by <d>. Hence my belief that these two have some separative or conjunctive function. (I have to admit, however, the <y> also seems sometimes to take the place of <o> before <k/f> or <t/p> (though rarely, if ever, after <q>); this is particularly noticeable in some of the captions to illustrations in the astronomical section of the manuscript – these most commonly begin <ok>/<of> or <ot>/<op> and it is here that we occasionally see <yk>/<yf> or <yt>/<yp>.)

(e) I have tried, for convenience of handling, to divide words into what I call “roots” and “suffixes.” This arrangement is show in the bottom of Plate 17. [Which is, as best as I can tell, the following table:-]

Roots: <ok>/<of>, <ot>/<op>, <qok>/<qof>, <ch>/<sh>, <s>, <d>, 2 [??] <lk>/<lf>

Suffixes: either (i) <e>, <ee>, <eee> followed by <y> or <dy>

or (ii) one or more of the following -

<an> <ain> <aiin> <aiiin>

<ar> <air> <aiir> <aiiir>

<al> <ail> <aiil> <aiiil>

<or> <ol>

Regarding the second type of suffix, some of the combinations are so rare that I have been uncertain whether to take any account of them at all. Some are very common indeed. It seems to me that each of these combinations beginning <a> has its own characteristic frequency which it maintains in general throughout the manuscript and independent of context except in cases where two or more <a> groups are together in series, as referred to later). These <a> groups e.g. <ar> or <aiin>, frequently occur attached directly to “roots,” particularly <od>, <ot>, <d> and <s>. <okaiin>, <qokaiin> and <daiin> rank high among the commonest words in the manuscript.

(f) There are however many examples of 2, 3, 4 or even 5 <a> groups strung together on end with or without spaces between them. When this occurs, there appears to be some selective preference. For example, <ar> is very frequently doubled, i.e. <ar ar>, whereas <aiin> which is generally significantly commoner, is rarely found doubled. Perhaps the commonest succession of three of these groups is <ar ar al>. <al> very frequently follows <ar>, but <ar> hardly ever follows <al>.

(g) <o>, which has a very common and very definite function in “roots,” seems to occur frequently in “suffixes” in rather similar usage to <a>, but nearly always as <or> and <ol>. <or aiin> is very common.

(h) The behaviour of the <a> (and <o>) groups has suggested to me that they may in fact constitute some form of spelling. It might be, for instance, that the manuscript is intended to demonstrate some very primitive universal language and that the author was driven to spell out the ends of words in order to express the accidence [i.e. the inflectional morphology] of an inflected language. If all the possible <a> and <o> combinations can occur, then there are 24 possibilities. They may, however, be modified or qualified in some way by the prefixed symbols <k>/<f>, <p>/<t>, <ok>/<of>, <op>/<ot>, <ch>/<sh>, <s>, <d>, 2 [??], etc., and I have not so far found it possible to draw a line anywhere. This, coupled with ignorance of the basic language, if any, makes it difficult to make any sort of attempt at solution, even assuming that there is spelling.

(i) <l>, usually preceded by <a> or <o>, is very commonly followed by <k>/<f>, much less commonly by <t>/<p>, with or without a space between. In this connection, I have become more and more inclined to believe that a space, though not intended to deceive, must not necessarily be regarded as a mark of division between two words or concepts.

(j) Speaking generally, each symbol behaves as if it had its own place in an “order of precedence” within words; some symbols such as <o> and <y> seem to be able to occupy two functionally different places.

(k) Some of the commoner words, e.g. <okeed>, <okeedy>, <qokeedy>, <odaiin>, <okar>, <okal>, <daiin>, <chedy> occur twice running, occasionally three times.

(l) I am unable to avoid the conclusion that the occurrence of the symbol <e> up to 3 times in one form of “suffix” and the symbol <i> up to 3 times in the other must have some systematic significance.

(m) Peter Long has suggested to me that the <a> groups might represent Roman numerals. Thus <aiin> might be IIJ, and <ar ar al> XXV, but this, if true, would only present one with a set of numbered categories which doesn’t solve the problem. In any case, though it accounts for the properties of the commoner combinations, it produces many impossible ones.

(n) The next three plates show pages where the symbols occur singly, apparently in series, and not in their normal functions. The column of symbols at the left in Plate 18 [i.e. the vertical column at the left edge of f49v] appears to show a repeating cycle of 6 or 7 symbols <t> <o> <r> <y> <e> <o> <k> <s>. In Plate 19 [i.e. f57v] the succession of symbols in the circles must surely have some significance. One circle has the same series of 17 symbols repeated 4 times, an interesting column of symbols. Plate 20 [i.e. f66r] also has an interesting column of symbols. In all three there are symbols which rarely, if ever, occur elsewhere.

(o) My analysis, I believe shows that the text cannot be the result of substituting single symbols for letters in the natural order. Languages simply do not behave in this way. If the single words attached to stars in the astronomical drawings, for instance, are really, as they appear to be, captions expressing the names or qualities of those stars, there can hardly be any form of transposition system involved. And yet I am not aware of any long repetition of more than 2 or 3 words in succession, as might be expected for instance in the text under the botanical drawings.