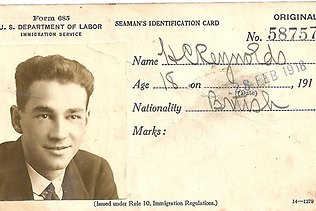

The hot cipher mystery news from Australia a few days ago was the intriguing suggestion that a certain “H. C. Reynolds” might well have been the “Unknown Man” found on Somerton Beach on 1st December 1948(AKA the “Tamam Shud” case). A couple of intrepid Cipher Mysteries readers decided to see what they could find out about this mysterious person: all they had to go on was a US seaman’s ID card dated 28th February 1918, which may or may not be genuine…

Cheryl Bearden & Knox Mix quickly found a number of references to an “H. Reynolds” / “H. C. Reynolds”, and very kindly left comments on the previous post here documenting what they had found. I’d already checked a number of free online databases of passenger / crew manifests without any luck, so guessed they were using ancestry.com, which has scans of quite a few passenger lists. Hence I decided to have a quick look here myself, to see if I could pick up on anything they might have missed: so here’s what I found…

* Manuka: dep. Wellington, arr. Sydney NSW, 19 Nov 1917. H. Reynolds, age 17, Assistant Purser, born Tasmania.

* Manuka: dep. Hobart, arr. Sydney NSW 17 Dec 1917. H. Reynolds, age 17, Assistant Purser, born Tasmania.

* Manuka: dep. Hobart, arr. Sydney NSW, 26 Jan 1918. H. C. Reynolds, age 17, Assistant Purser, born Australia.

* Niagara: dep. Vancouver B.C. via Auckland, arr. Sydney NSW 17 Feb 1918. H. Reynolds, age 18, Assistant Purser, born Hobart.

* Niagara: dep. Vancouver B.C. via Auckland, arr. Sydney NSW 20 Apr 1918. H. Reynolds, age 18, 2nd Mate, born Hobart.

* (Ulimaroa: dep. Hobart, arr Sydney NSW, 22 Nov 1920. H. C. Reynolds, male passenger.)

The RMS (“Royal Mail Service”) Niagara regularly crossed the Pacific Ocean between Vancouver, Sydney, Auckland and Suva (in Fiji) for more than 25 years, making it the furthest-travelled steamship ever. But what, then, of Reynolds’ ID card? What for me seals the deal is a nice blog post I found by Haley Hughes talking about letters her great-grandfather Geo. W. W. B. Hughes sent to her grandfather Noel while travelling on the RMS Niagara back in 1931:-

“The ship departed Sydney on 25 June, with stops in Auckland, departing 30 June; Suva, Figi Islands, departing 3 July; Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands, departing 10 July; and Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, arriving 16 July, and Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, arriving 17 July.”

I think this gives us enough broad brushstrokes of how the journey worked to finally tie all the loose ends together!

It seems very likely to me that Reynolds first came on board the RMS Niagara at Suva or Auckland on its way to Sydney (perhaps to replace a sick crew member?). He then continued with the Niagara on its next trip across the Pacific to Vancouver, stopping off in Honolulu for the first time in his life. This was almost certainly where he picked up his US temporary seaman’s identification card, the one that was to become his keepsake of the experience: looking again at his photo in it, I think he looks excited, perhaps even a little exhilarated by the whole experience. Perhaps – if Reynolds was indeed the Unknown Man – this is also where he took to Juicy Fruit chewing gum, possibly as a (arguably slightly unhealthy) memento of Hawaii.

All the same, this was only a brief peak moment for him, for it seems that not long after this he left his life on the sea. Could it be that his experience dealing with the New Zealand gunners on board the RMS Niagara stirred something in him, causing the 18-year-old Reynolds to sign up to fight in the Great War?

Post-WWI, the next glimpse we see of H. C. Reynolds might possibly be as a passenger between Hobart and Sydney in November 1920 on the Ulimaroa… but it’s hard to be sure. It seems entirely possible to me that he still had a family in Hobart: a presumably quite different “H. Reynolds” made a number of trips between Hobart and Sydney early in the new century – might this have been H. Reynolds Sr?

Will all this be enough to track Reynolds down? The problem with ancestry.com (and, in fact, the Internet as a whole) is that it’s easy to fool yourself that records accessible through it are even remotely complete, when they simply are not. The world has many million times more data than that, but you just have to get at them the hard way. Still, as Cheryl and Knox pointed out, it seems that we know that his 18th birthday fell between 27 Jan 1918 and 17 Feb 1918, so I’d like to think we’re doing reasonably well! Next stop, Tasmanian off-line birth records, eh? 😉

PS: ancestry.com.au lists a “Horace Charles Reynolds” born in 1900 to Edwin Reynolds and Mary Ann Matilda Reynolds, with the birth registered at Hobart, Tasmania: and a Reynolds family tree listed there has “Horace Charles Reynolds” born 8 Feb 1900 in Triabunna, Tasmania, but (it is claimed) dying on 16 May 1953 in Hobart. Does this rule out H. C. Reynolds as the Unknown Man, or might there possibly have been two people with the same name? It’s all pretty specific stuff, so perhaps the Anonymous Lady who proposed Reynolds in the first place might know a little bit more to help narrow this down?