Two long(-ish) form Voynich manuscript articles emerged recently, one in the Jewish magazine The Tablet “Tablet Magazine”, the other in the New Yorker’s online blog section. These tell us quite a lot – though not really about the Voynich Manuscript itself, but rather about how the Voynich Manuscript is now perceived.

The first article, by Batya Ungar-Sargon, is called Cracking the Voynich Code: The quixotic quest to read meaning in the patterns of a bizarre manuscript that has bedeviled scholars for years.

Her basic take is that “the Voynich Manuscript has become a beacon for a secular community of quasi-Talmudic scholars whose interpretive ingenuity and stamina have few parallels“, so her piece is built around interviews with several of them (including the “patient, tireless” Gordon Rugg, and the “deeply humble” Rich SantaColoma). [She also talked with me on the phone for an hour, but perhaps I didn’t fit her template 😉 ].

Taken as a whole, fitting her article into a primarily Jewish-interest magazine was always going to be a bit of stretch: William Friedman was Jewish, sure, but that’s a small piece of material to make a full-length dress out of. I can’t help but wonder whether Batya’s ambition is to write long-form pieces for the New Yorker, and that this was a try-out for her portfolio. She clearly writes well, but I don’t think her journalistic instincts are yet fully honed – her article, in my opinion, is still more ‘relating’ than the literary reportage to which she aspires.

The second article – The Unread: The Mystery of the Voynich Manuscript – by Reed Johnson is, coincidentally enough, from the New Yorker blog section. As such, it’s a kind of New Yorker long-form take on a blog post, i.e. longer than a normal blog post, but quite a lot shorter than a typical New Yorker article (I used to subscribe to it, though how I ever found enough time to read each issue I don’t know 🙂 ).

This isn’t Ungar-Sargon-style journalism, but is instead Reed’s telling the story of how he came to waste three years (only three years? Pshaw!) on the Voynich Manuscript – basically, while trying to write his own “Dan Brown–style thriller”, having nearly completed his “M.F.A. in fiction at the University of Virginia” in 2010. He tries to introduce a little light drama into his account (Did he crack the Voynich? Did he finish his book?) but with enough of a wink to astute readers that they know the resolutions long before the end.

Unlike Batya, Reed is not an observer looking in on the Voynich research world from the outside, but is instead an active participant in what he calls the “often fractious” Voynich mailing list. His feeling about this is that “If crowds have any wisdom, soon we should see the fruits of a more recent deciphering project: Internet crowdsourcing“. And yet, he also wonders whether it would be a disappointment for the Voynich Manuscript to be decrypted – that, “no matter how thrilling such a text might be, it [would] remain a disappointment for being closed off, completed — for being, in the end, no longer a mystery“.

My own conclusion is that the Voynich mailing list has become more part of the problem than part of the solution: and that the extraordinarily productive collaboration its early days saw was more down to the small number and high calibre of the participants (Jim Reeds, Jim Gillogly, Jacques Guy, etc), most of whom left the list long ago. Really, the collective wisdom of the crowd very much depends on the crowd you happen to be dealing with: though Reed stops short of showing his hand in this regard, so we end up knowing what happened but not his thoughts or feelings about it. Perhaps the whole card game hasn’t yet concluded for him.

What’s nice about these two articles is that, for all their differences, they are both good examples of clear-headed contemporary writing about the Voynich Manuscript, far from the lurid wodges of mystery-soaked ahistorical fragments I frequently used to see. Indeed, both give an account of the Voynich’s history that is broadly correct, something which simply never happened even a decade ago: perhaps the radiocarbon dating has helped validate the Voynich as a “proper” subject.

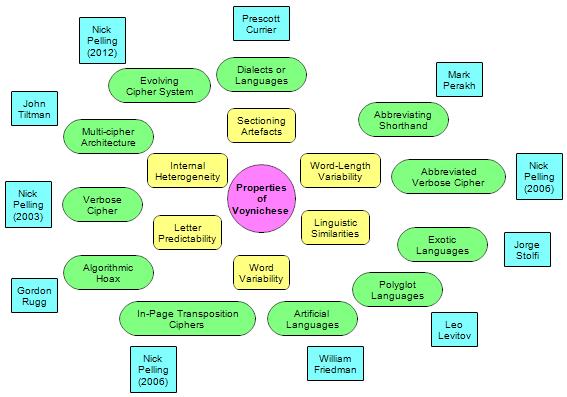

And yet… it’s as if something (or someone) is missing from the whole party. The Voynich Manuscript has had many of the best codebreakers of the age (the Friedmans, Manly, Tiltman, etc) examine it closely: yet as these articles show, a lot of contemporary discourse still revolves around the – frankly rather foolish and shallow, I think – postmodernist cipher/hoax tension as exemplified by Gordon Rugg and Rich SantaColoma.

To my mind, it’s as if something really important is missing from the whole conceptual landscape of how the Voynich is perceived, that everyone is somehow in the wrong kind of doubt. We’ve collectively travelled a really long way forward, for sure, but the ideas and insights gained on that journey have all been zapped by a kind of “motivated learning” paralysis, where debate is held in a stasis between powerful epistemological agendas.

It often feels as though, myself excepted (and who listens to what I say, ha!), the Voynich-as-a-genuine-historical-artefact point of view has no champion. I genuinely tire of the way people continually generate possible alternative histories for it, when I’m just about the only person trying to reconstruct the mainstream history they’re so busy fighting against.

I want to ask those “theorists”: why do you find the idea that the Voynich Manuscript was made basically when its radiocarbon dating says so dreadfully upsetting? Why do you invest so much time and effort into identifying outlandish alternatives that might possibly be made to work (with a few well-chosen tweaks to the mainstream historical timeline)? Do you not see that, by kicking back so hard against a straightforward historical account that hasn’t even been written yet, you are yourself holding everything back? Can you not see that by doing this you have become part of the problem, not part of the solution?

That is the Voynich Manuscript debate that’s missing, the elephant in the room that nobody wants to talk about. But nobody is writing that particular article, and I’m not sure anyone ever will… and perhaps we’re all worse off for that silence.