Back in August 2010, I posted up some observations on the Voynich Manuscript’s Quire 20, which included:

* Tim Tattrie pointed out that ‘x’ appears on every folio of Q20 except the first (f103) and the last (f116)

* I noted that these ‘x’ characters often sat next to ‘ar’ and ‘or’ pairs, e.g. arxor / salxor / kedarxy / oxorshey / oxar / shoxar / lxorxoiin, etc.

* Tim Tattrie also pointed out that the paragraph stars on f103 and f116 are notable because they don’t seem to have tails

* The tail-less paragraph stars on f103r looked to me as though they had been added in at a later stage

* Elmar Vogt pointed out that most of the paragraph stars followed an empty-full-empty-full pattern, except for “f103r, f104r and f108r”

* “The notion that Q20 originally contained seven nested quires (as per the folio numbering) seems slightly over-the-top to me”

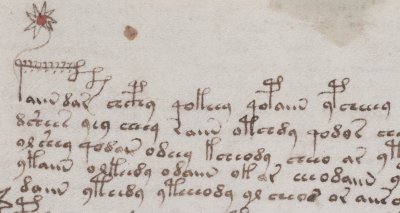

* f103r doesn’t “look” it should be the first page of Q20, but f105r (with a nice ornate gallows) does:-

From these, I tentatively concluded (way back then) that Q20 might well therefore have originally been written as two separate codicological parts, which I proposed calling “Q20A” and “Q20B”. It was certainly an interesting suggestion… and, as I’ll explain below, one that I suspect was quite close to the truth, though admittedly not the whole story.

The “ytem” / “ydem” star tails

I then posted again in September 2010, where I proposed that the tails of the paragraph stars had been written first: and that they had been then been accessorized with a star to hide them from view.

That is, the tail is the meaning (they all read ‘y’ if you look closely), and the star is the deception. But what does the ‘y’ mean? Well, lists in countless medieval documents are very often itemized using the word “item” or “ytem”: which is why we use the word “itemized”, of course. So it seemed (and still seems) overwhelmingly likely to me that the paragraph star tail ‘y’ was short for “ytem”, and that each Q20 star with a tail marked the start of an item.

If you count up all the paragraph stars with tails, you get the following numbers:

f103r 0 + 19 (i.e. no stars with tails, but 19 stars without tails)

f103v 0 + 14

f104r 13

f104v 13

f105r 10

f105v 10

f106r 15

f106v 14

f107r 15

f107v 15

f108r 16

f108v 16

f109r ?? \

f109v ?? -\ missing

f110r ?? -/ bifolio

f110v ?? /

f111r 17

f111v 5 + 14 (something a little odd would seem to be going on here)

f112r 12

f112v 12 + 1

f113r 16

f113v 15

f114r 13

f114v 12

f115r 12 + 1

f115v 13

f116r 0 + 10

Add up all the stars with tails and you get 264: if the four pages from the missing central bifolio (f109 / f110) each contained 15 stars, we would seem to get a total of closer to 264 + 4 x 15 = 324 items (as opposed to starred paragraphs). I don’t know exactly what that means, but it is what it is.

Quire 20 “Block Paradigm”

When I revisited Q20 in 2014 , it was to propose that we might also profitably look for a “block paradigm” match to Quire 20. By this, I meant that we should go a-hunting for an existing book of secrets from the right time frame from which Q20’s contents might well have been copied / encrypted. As a pretty good candidate, I suggested BnP MS. 6741, which contains a set of 359 numbered recipes (plus various rhymes) compiled from various sources by Jean le Bègue / Jehan le Bègue [1368-1457] in Paris in 1431: in Latin.

But then again, when in the past others have suggested that this section might just as well contain 360 elements (as in per-degree astrology), or even 365 elements (one for each day of the year), it has been pointed out by way of response that the number of starred paragraphs doesn’t seem to fit: we have too many stars. “My God, it’s (too) full of stars”, one might reasonably say (if you are a cinema buff, that is).

This is because if you take Q20 as a whole, you would expect its total number of paragraph stars to be around 323 + (15 x 4) = 383, which is about 20-25 stars too many for (what I, at least, consider) the most likely scenarios (359 / 360 / 365).

Yet if you restrict yourself to “ytem stars” (i.e. stars with tails), it seems that you end up with roughly 324 “ytems”, which would seem to be 35 or so stars too few.

So how do all these odd-shaped jigsaw pieces slot together? Quire 20 would seem to be quite the three pipe problem, as Sherlock Holmes would have (fictionally) said. 🙂

…or is it?

How to read this hidden book

Building on all of the preceding observations (and inspired by comments recently left here by Rene Zandbergen), here’s how I think Q20 was written, and how we should try to “read it” – that is, how our eyes should sequence its pages and comprehend its content.

It seems likely to me that the ornate gallows character on f105r marks not the start of a quire, but the start of a book – or, at the very least, the very first “ytem” in that book. Furthermore, if we group all the pages with “ytem” tailed paragraph stars together and put this at their front, f105r would have been either (a) the first part of a free-standing book (“Q20A”, as I proposed before), or (b) the first part of a book whose presence inside Q20 was concealed by fake paragraph stars. Either way, I now feel confident that we should be reading f105r as if it were the first part of the hidden book.

In which case, the fake-looking paragraph stars on f103r, f103v and f116r would indeed be fake, added to visually conceal the start and end of the book within Q20. f103r has nineteen of these fake stars crammed down its left margin: the more you look at them, the more fake they look, I think.

So: if we put the f103-f116 “fake paragraph star” bifolio to one side, and place the f105-f114 bifolio as the outermost ‘wrapper’ of the hidden book, the question then comes whether we can infer from any other statistical or visual properties what the nesting order (and orientation) of the other five bifolios inside it was (i.e. when the book was in its original, ‘alpha’ state).

Tim Tattrie insightfully noted in a comment here that:

* “lo” as a separate word is only found in f104r, f106r and f108v.

* “rl” as a separate word, or word beginning is only found in f104r, f108v and f113r.

* “llo” as a series of letters is only found in f104r, f108v, f111v, f113v, f116r

I think this suggests some kind of semantic, content-based link between f104r and f108v: and hence that f108v and f104r may well have originally sat facing each other in the original bifolio layout.

Unfortunately, I haven’t yet noticed any Q20 colour transfers dating back to its earliest phases of composition. The big reddish smudge on the top right of f103r (where some of the Voynichese letters inside it have been badly emended in a later hand) seems to have happened after the pages were in their final nesting order, and the same seems true of the (initially green, but then fading away quickly) stain at the centre top of the Q20 pages.

There are also some tiny green paint splodges on the very right hand edge of f104r: but these seem to me to have almost certainly been added by accident when the heavy painter was painting Quire 19 (f103 is a little bit smaller than f104, so the outermost edge of f104 stuck out a little beyond f103, catching the drips from the paint brush).

All in all, the problem with trying to reconstruct Q20’s original nesting order is that it was left in a very clean (i.e. unmessed-around-with) state, probably because it was the least visually intriguing quire. So unless we can find a magical Raman-style way of picking up close-to-invisible inter-folio paint transfers from the paragraph stars, we don’t seem to have much else to work from.

Hence at this point, I’m basically out of ideas: are there any other sources of information (whether visual, statistical etc) you can suggest that might help us reconstruct Quire 20’s original folio sequence?