Apart from the case of the Somerton Man, has any other police investigation ever revolved around a book left in a complete stranger’s car? Personally, I’d be surprised: this seems to be a unique feature of the whole Somerton Man narrative.

But what, then, of the obvious alternate explanation, i.e. that the Rubaiyat was in the car already? For all the persuasive bulk the dominant explanation has gained from being parroted so heavily for nearly seven decades, I think it’s time to examine this (I think major) alternative and explore its logical consequences…

Gerry Feltus’s Account

To the best of my knowledge, Gerry Feltus is the only person who has actually talked with the (still anonymous) man who handed the Rubaiyat in. So let us first look at Feltus’ account (“The Unknown Man”, p.105) of what happened at the time of the Somerton Man’s first inquest when the police search for the Rubaiyat was mentioned in the press:

Francis [note: this was Feltus’ codename for the man] immediately recalled that his brother-in-law had left a copy of that book in the glove box of his little Hillman Minx [note: not the car’s actual make] which he normally parked in Jetty Road. He could not recall him collecting it, and so it was probably there. He went to the car and looked in the glove box – yes, the book was still there. To his amazement a section had been torn out of the rear page, in the position described by past newspaper reports.

“Ronald Francis” then telephoned his brother-in-law:

Do you recall late last year when we all went for a drive in my car, just after that man was found dead on the beach at Somerton? You were sitting in the back with your wife and we all got out of the car, the book you were reading, you put in the glove box of my car, and you left it there.

To which the brother-in-law replied:

No it wasn’t mine. When I got in the back seat, the book was on the floor; I fanned through some pages and thought it was yours, so when I got out of the car I put it in the glove box for you.

A while back, I pressed Gerry Feltus for more specific details on this: though he wouldn’t say what make of car the “Hillman Minx” actually was, he said that the man told him that the book turned up “a day or two after the body was found on the beach, and during daylight hours“. Gerry added that “Francis” was now very elderly and suffering from severe memory loss. Even so, he said that “I have spoken to Francis, his family and others and I am more than satisfied with what he has told me“.

Finally: when “Francis” handed the Rubaiyat to the police, he “requested that his identity not be disclosed”, for fear that he would be perpetually hounded by the curious. Even today (2017) it seems that only Gerry Feltus knows his identity for sure: though a list of possible names would include Dr Malcolm Glen Sarre and numerous others.

Newspaper Accounts

All the same, when I was trying to put everything into a timeline a while back, I couldn’t help but notice that Gerry’s account didn’t quite match the details that appeared in the newspapers at the time:

[1] 23rd July 1949, Adelaide News, page 1:

[…] an Adelaide businessman read of the search in “The News” and recalled that in November he had found a copy of the book which had been thrown on the back seat of his car while it was parked in Jetty road, Glenelg.

[2] 25th July 1949, Adelaide Advertiser, page 3:

A new lead to the identity of the Somerton body may have been discovered on Saturday when Det.Sgt. R. L. Leane received from a city business man a torn copy of Fitzgerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam said to have been found in his car at Glenelg about last November, a week or two before the body was found.

The last few lines of the poem, including the words “Tamam shud” (meaning “the end”) have been torn out of the book.

When the body was searched some time ago a scrap of paper bearing the words “Tamam shud” was found in a pocket.

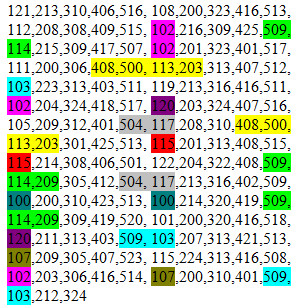

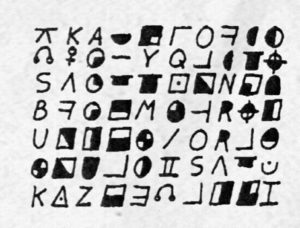

Scrawled in pencilled block letters on the back of the cover of the book are groups of letters which appear to be foreign words and some numbers.

These, it is hoped, may be of assistance in tracing the dead man’s identity.

The business man told Det.Sgt. Leane that he found the copy of the Rubaiyat in the rear of his car while it was parked in Jetty road Glenelg, about the time of the RAAF air pageant in November.

He said he had known nothing about the much-publicised words “Tamam shud” until he saw a reference to them on Friday.

[3] 26th July 1949, Adelaide News, page 1:

The book had been thrown into the back seat of a motor car in Jetty road, Glenelg, shortly before the victim’s body was found on the beach at Somerton on December 1.

[…]

Although the lettering was faint, police managed to read it by using ultra-violet light. In the belief that the lettering might be a code, a copy has been sent to decoding experts at Army Headquarters, Melbourne.

Why Do These Accounts Differ?

The Parafield air pageant mentioned unequivocally in the above newspaper accounts was held on 20th November 1948, ten days or so before the Somerton Man was found dead on Somerton Beach. Yet Gerry Feltus was told by “Ronald Francis” himself that the book turned up “a day or two after the body was found on the beach”. Clearly, these two accounts can’t both be right at the same time.

I of course asked Gerry directly about this last year: by way of reply, he said “Don’t believe everything you read in the media, eg; ‘The business man told Det. Leane…. etc…’.“. Moreover, he suggested that I was beginning “to sound like [Derek] Abbott”, who had “nominated the same things as you”.

This is, of course, polite Feltusese for “with respect, you’re talking out your arse, mate“: but at the same time, all he has to back up this aspect of his account – i.e. that the book turned up after the Somerton Man was found, not ten days before – is “Ronald Francis”‘s word, given half a century after the event.

Hence this is the point where I have to temporarily bid adieu to Gerry Feltus’s account, because something right at the core of it seems to be broken… and when you trace the non-fitting pieces, they all seem to me to lead back to the Rubaiyat and the car.

So… what really happened with the Rubaiyat and the car? Specifically, what would it mean if the Rubaiyat had been in the car all along?

The Rubaiyat Car Theory

If the Rubaiyat was already in the back of the “little Hillman Minx”, it would seem to be the case that:

(*) Ronald Francis had no idea what it was or why it was there

(*) Ronald Francis’ brother-in-law had no idea what it was or why it was there

(*) …and yet the Rubaiyat was connected to that car in some non-random way

(*) …or, rather, it was connected to someone who was connected to the car

Given that one of the phone numbers on its back was that of Prosper McTaggart Thomson – a person who lived a quarter of a mile away from where “Ronald Francis” lived or worked, and who (as the Daphne Page court case from five months earlier demonstrated beyond all doubt) helped people sell cars on the black market by providing fake “pegged-price” documentation – it would seem reasonable at this point to hypothesize that Prosper Thomson may well have been the person who had sold “Ronald Francis” that specific car.

There was also a very good reason why many people might well have been looking to sell their cars in November 1948: the Holden 48-215 – the first properly Australian car – was just then about to be launched. Note that the “little Hillman Minx” could not have been a Holden if it had been driven to the Parafield air pageant, as the very first Holden was not sold until the beginning of December 1948:

If “Ronald Francis” had just bought a car in (say) mid-November 1948, I can quite imagine him proudly taking his wife, his brother-in-law and his wife off to the Parafield air pageant for a nice day out.

If Prosper Thomson’s behaviour in the Daphne Page court case was anything to go by, I can also easily imagine that the person who had sold that car might have wondered if he was being swindled by the middle man. In his summing up, the judge said that “[t]he defendant [Thomson] had not paid the £400 balance, and had never intended to do so“: so who’s to say that Thomson was not above repeating that same trick, perhaps with someone from out of town?

Perhaps, then, the person whose Rubaiyat it was was not Prosper Thomson himself, but the person from whom Prosper Thomson had just bought the car in order to sell it to “Ronald Francis”.

Perhaps it was this person’s distrust of Thomson’s financial attitude had led him to hide the Rubaiyat under the back seat of the car, with the “Tamam Shud” specifically ripped out so that he could prove that it was he who had sold the car to Thomson in the first place.

And so perhaps it was the car’s previous owner who was the Somerton Man, visiting Glenelg to track down the owner of his newly sold car, simply to make sure he hadn’t been ripped off by Prosper Thomson.

The Awkward Silence

I’ve previously written about how social the Somerton Man seemed to have been, and how that jarred with the lack of helpful response the police received. For all its physical size, Australia still had a relatively small population back then.

So perhaps the silence surrounding the Somerton Man cold case will turn out to be nothing more than that of jittery people buying and selling cars not through dealers, people who the Price Commissioners pegged prices had effectively turned into white-collar criminals – for how many professionals were so well-off in post-war Australia that they could afford to be principled about losing £400 or more in the sale of their shiny American car?

Incidentally, it has been reported that on the back of the Rubaiyat were written two phone numbers: one of which was the (now-famous) phone number for the nurse Jo Thomson (which her soon-to-be-husband Prosper Thomson was also using for small ads in the newspapers), while the other was allegedly for a local bank.

These are the two things people selling black market cars need: the number of the middle man who was laundering the transaction, and the number of bank to make sure cheques clear (remember that a dud cheque to pay for a car was ultimately what triggered the Daphne Page court case).

But the other thing such people need is an absence: an absence of discussion about the transaction. And if “Ronald Francis” had only just bought his car on the black market through Prosper Thomson (thanks to Price Commission pegging, only about 10% of car sales back then went through official car dealer channels), he would surely have had a very specific reason not to want the details of his sale explored and made public.

And so I wonder whether this was the real reason why Ronald Francis didn’t want his name revealed: because if the police were to understand the web of dealings that had brought the Somerton Man to Glenelg, that would inevitably make it clear that the two men were the participants in a black market car sale, one which – though widely practised – was still a Price Commission offence with stiff penalties.

Along those same lines, I also wonder whether it was Ronald Francis himself who erased the pencil writing from the Rubaiyat’s back cover, to try to cover at least some of the tracks that might lead police in his direction. Of course, we now know that SAPOL’s photographers were able to use ultra-violet photography to (mostly) reconstruct the letters: but this may well not have been known to him at the time.

Please note that I’m not saying this is the only plausible explanation for everything. However, insofar as it tackles (and indeed resolves) a large number of the trickiest aspects of the case, it’s at least worth considering, right?

A Final Note

To be clear, when I ran this whole Rubaiyat Car suggestion past Gerry Feltus (admittedly in an earlier iteration), he dismissed it out of hand (though without any actual evidence to back up his position):

“I will not go into the possibility that the man purchased his car from Prosper. It is an absolutely rubbish suggestion that has no credibility. Poor old Prosper. He must have been the only ‘black market’ racketeer in Adelaide. From my knowledge of the climate during that relevant period he was a ‘nothing’.”

Well, Gerry was absolutely right insofar as that in 1948 Prosper was a small-time black marketeer, a mere minnow in the Melbourne-dominated black market car pool: but all the same, he was a minnow that lived extremely close by.

I suspect the real problem here is that if the mainstream story is wrong – that is, if Ronald Francis’ car had not long before (like so many others at the time) been bought at a premium on the black market, and if Francis had told white[-collar] lies to try to cover up his part in an illegal transaction once he realized what had happened – then people have been concealing their true involvement with what happened for nearly 70 years, not because of murder but because the price control legislation made criminals of nearly everyone selling their car.

And so it might well be that Gerry Feltus (and indeed just about everyone else) has been viewing the Somerton Man as entirely the wrong kind of mystery: not a police cold case, but a Price Commission cold case. How boringly middle class!