An intriguing email just arrived on Cipher Mysteries’ virtual doormat: recent blog subscriber Anna Castriota (thanks for writing, Anna!) asks whether I think there is any sign of filigree in the Voynich Manuscript.

Of course, as per normal with the VMs, the answer is a “tentative maybe”. There are good grounds for believing that its author had been exposed to an eclectic range of artistic influences that we can glimpse expressed in different ways, so it would not be a huge surprise if filigree was also on this list. But… was it?

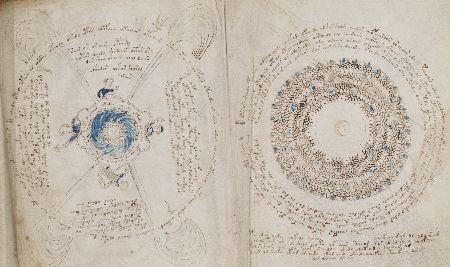

Technically, filigree is formed from twisted gold or silver wires: and if you go looking for its characteristic shape in the VMs, I think you might just about note a resemblance in the exterior lines of the sun face and moon face “calendar” pages.

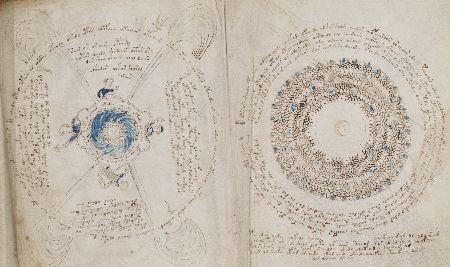

Voynich Manuscript, f67r1 (“moon face calendar”), detail

Voynich Manuscript, f68v1 (“sun face calendar”), detail

Of couse, if you were to point out that this is a pretty tenuous comparison, I’d have to agree. 😉

However… I suspect it is instead rather more useful to hunt through the VMs looking for the spirit of Quattrocento filigree decoration, wherein goldsmiths repetitively filled out basic designs with dense filigree twists. If I’ve got the history right, this was a mid-Quattrocento precursor to what Warburg called the horror vacui, the abhorrence of emptiness – a fashion that crept into decorative artworks after the 1480 rediscovery of Nero’s Golden House (Domus Aurea) with its numerous busy images – according to which artists strove to fill every inch of decorated surface with a mass of buzzing details. An accessible source on these ‘grotesques’ is Chapter 7 of Joscelyn Godwin’s “The Pagan Dream of the Renaissance”: but (unless you happen to know better) I happen to think filigree goldsmiths basically got there first.

As far as the Voynich Manuscript goes, I think a relevant piece of forensic inference is that there are good codicological grounds for concluding that many of its later (more sophisticated) drawings were executed in two basic passes: (1) a primary layout pass (probably expressing the basic idea) , and (2) a secondary decorative pass (probably concealing that basic idea, for whatever reason). So, our research question then becomes whether we can detect this filigree design spirit at play in the Voynich Manuscript’s more decorated pages…

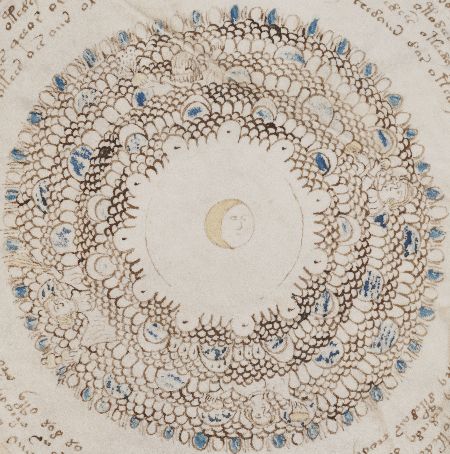

And you know, on balance, I think that we probably can: the key example I would give is the pair of “magic circle” pages. These comprise two circular diagrams on adjacent pages, one with a sun shape in the centre (f85r2) the other with a moon (f86v4), but both surrounded by four human figures at 90 degrees to each other.

What, you can only see the four characters on the left-hand magic circle? Well… I’ll come to that shortly.

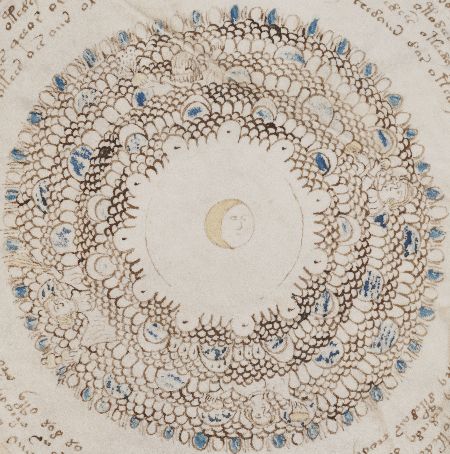

What is particularly curious about these is that the second “moon” magic circle drawing has been obscured by layer upon layer of dense decoration, such that the four figures around the centre (along with a series of other details) are barely visible. That is, while the left one is completely undecorated, the right one is abundantly overdecorated to the point of total coverage.

In the immortal words of Rolf Harris CBE, “Do you know what it is yet?” If you’re still having trouble seeing this, here is that same magic circle one last time with all the concealing decorative stuff removed (though fairly inexpertly, and at low resolution):-

And no, I too have no idea what this denotes or means. But I am pretty sure (from the different inks that were used) that this diagram was drawn in multiple stages, with something not dissimilar to the stripped-out version being the result of the first (expressive) drawing phase, and the preceding image being the result of the second (concealing) phase.

Whatever was originally depicted here, it is hard not to conclude that the author wanted to obscure the structure of this particular page, and so filled in every available space with a dense thicket of misleading detail. Ultimately, this reminds me very strongly of the repetitive decorative nature of filigree decoration – which is why I pointed towards a “tentative maybe” right at the top of the page. 🙂

You can also see this kind of busy, space-filling activity at play on the nine-rosette fold-out page (which is actually on the reverse side of the same folio as the magic circles pages). Here again you can see what appears to be the initial expressive phase (in lighter ink) and a later space-filling phase (in darker ink, and painted in). Quite why this should be so remains a mystery, but I do suspect that here again it was added to distract attention away from the original content of the page.

All of which therefore suggests that it might be a (quite literally) revealing exercise to look at the nine rosettes through multispectral filters, to see if we can determine if they similarly began life unadorned, but were then über-decorated at a later stage. Perhaps the right question to be asking of all the drawings hasn’t to date really been asked: what is signal, and what is noise?

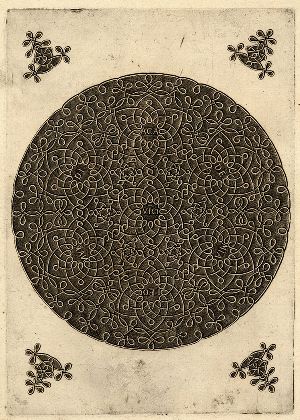

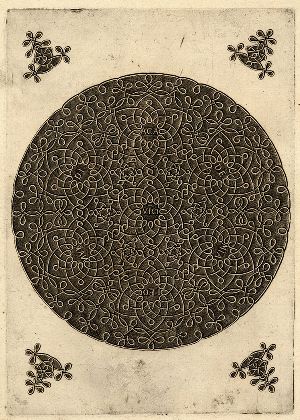

Of course, it has been suggested that these filled-out circular designs are merely scribal doodles, time-filling graffiti, a bored student in his medical class, etc: but then again, nobody now looks at the “Academia Leonardi Vi[n]ci” circular knot roundel prints from circa 1500 and calls them mere doodles, so what are the rules in this game, hmmm? Or is this just symptomatic of one of those semantically irregular verbs, that shade away when applied to people you don’t much care for: “I design, you sketch, he/she doodles“?

“Academia Leonardi Vici”, print at the British Museum “(After) Leonardo da Vinci”

I sometimes get accused of reading too much into all these fragments: but when you put them together, they very often do afford us glimpses into their secret shared life. This, in the end, is what Art History is all about: for all its forensic aspirations, it is largely a romantic discipline, built on the faint hope that the notion of technique relied upon by each generation of artist will be sufficiently expressed in their works to reconstruct a narrative of continuity across the centuries.

But sometimes, it’s hard to actually put this into practice without feeling somewhat akin to “The Mentalist”: empathetically channelling a torrent of details to bring them back to life as a stream of narrative. But is it only in TV Land that this approach can solve whodunits, or is “The Mentalist” actually a closet art historian? [*]

[*] And yes, I did happen to see “The Mentalist” Episode 1-13 (“Paint It Red”) where Patrick Jane switched a pair of canvases to get a stolen $50m 15th century painting back from a Russian mobster. Be assured that proper art historians don’t do that (well, not often, anyway). 😉