While recently looking into the ‘pm9’ that Thomas Sauvaget found on Cod Sang 839 & trying to understand its relation with Cod Sang 840 and Cod Sang 841, I emailed St Gallen’s manuscript cataloguer Philipp Lenz for a little more information.

Interestingly, his opinion is “that this kind of quire numbering is [not] as extraordinary as you think” and though he unfortunately did not “have the time to look for specific examples of identical quire numbering“, he just happened to have a manuscript on his desk with the same kind of numbering in its text: Cod Sang 688.

Even though Cod Sang 688 has not been fully digitized, Prisca Brülisauer at the St Gallen library hen very kindly emailed me through PDF scans of them: Cod Sang 688 p.174 and Cod Sang 688 p.175.

What did I learn from this? Overall, I get the impression of a good scribe writing fast, thinking and abbreviating to fit the text inside two fairly narrow columns. Given that, I’m pretty sure the scribe isn’t abbreviating the Roman ordinals in a consistent manner or system: though we do (exactly as Philipp Lenz points out) see ‘4t9’ and ‘6t9’, the remainder are abbreviated in a fairly arbitrary manner.

What is also interesting to me is that the tension between Roman numbers and Arabic digits comes out in other ways, such as the ‘iiij’ on p.174 that the scribe has quickly clarified with a 15th century ‘4’ immediately above it. Perhaps Thomas Sauvaget and Philip Neal will have their own comments on these pages too! 🙂

Just so you know, Scherrer’s 1875 St Gallen catalogue dates it to “min. v. J. 1430 […] geschrieben von Fridolin Vischer in Mollis” – Mollis is a Swiss town in the Canton of Glarus, unsurprisingly, not too far from St Gallen. Cod Sang 688 is also linked with Cod Sang 686 and Cod Sang 687.

Oh, and if you’re wondering if there might be a Franciscan connection in all this 🙂 , Cod Sang 686 contains:-

S. 264-265: Epistola lectoris ord. fr. min. Friburg. ad. plebanos in Schoenowe et in Tottenowe de baptismo pueri in utero et Responsum de poenitentia publica. It. Epistola parochi ad abbatem S. Trudberti pro absolutione poenitentis.

The Franciscan Order of Friars Minor in Fribourg did indeed have a library. Bert Roest’s Franciscan library bibliography lists:

Renaud Adam, ‘Peter Falck (ca. 1468-1519) et ses livres: retour sur une passion’, Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Geschichte 56 (2006), 253-272.[info on Capuchin library of Fribourg, Switzerland]

Pascal Ladner, ‘Zur Bedeutung der mittelalterlichen Bibliothek des Franziskanerklosters in Freiburg’, in: Zur geistigen Welt der Franziskanerim 14. und 15. Jahrhundert. Die Bibliothek des Franziskanerklosters in Freiburg/Schweiz, ed. Ruedi Imbach & Ernst Tremp, Scrinium Friburgense, 6 (Freiburg/Schweiz, 1995), 11-24.

Romain Jurot, ‘Die Inkunabeln des Franziskanerklosters in Freiburg/Schweiz’,Freiburger Geschichtsblätter 81 (2004),133-217.

Just so you know! 😉

That’s worth singing about, I think.

(I’m in Corinth at present: will see what Franciscan links there might be)

– that’s *the* Corinth, of course.

Francisan provinces and houses c.1350

http://users.bart.nl/~roestb/franciscan/province.htm

There you go! Whizzing by at Web speed! I wondered about the spelling of Friburg. We have “Frey folk” in our earliest family history.

Now that writing sample is even “crisper” than the VM, even though it was written at great speed. Are you now going to have a dialect with which to compare/translate the VM script?

Oh boy!

Nick – re Franciscans.. and I’m relying on your long memory here..

I’ve noticed a paragraph at Voynich.nu which reads:

Possibly a missionary to the Far East, in an early attempt to convert Chinese (or another oriental language) to an alphabetic script. This theory is based on certain peculiar text statistics and is by no means disproved, but there is difficulty with the fact that the entire MS has a Western European look. A specific connection (e.g. encoding) with any specific oriental language has also not yet been proposed.

http://www.voynich.nu/origin.html

The page says the ideas are linked to their original proponents on another page, but this one does not seem to be there. Can you recall who (likely several) persons before me suggested that?

PS I don’t mean so much the bit about converting an oriental language, so much as the [Franciscan or Dominican] missionary thing.

Not trying to claim credit for the idea – quite the opposite. A little tired of labouring at length, presenting results, and learning it is all ‘been-there-done-that’.

bdid1dr

“re you now going to have a dialect with which to compare/translate the VM script”

I’ll fold my collar under and put a dollar on a relic of Kushani/ Bactrian see script as written there (at left)

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d6/KushanCoinage.jpg

and I’m sure someone else has thought of it before(!)

or, more hopefully Maghadi.

Hello Nick,

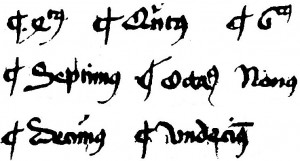

it’s nice to have these scanned pages with VM-like shorthands: the one for ‘sextus’ is exact indeed, while the one for ‘quartus’ has an extra ‘t’ compared to the VM.

I think that Philipp Lenz is right when he says such shorthands are not that rare: while browsing a different library in the past few days I’ve found similar examples, including one very close match. I’ll mention them on my blog this afternoon. I still think it contains valuable geographical information.

Thomas: I suspect that though Philipp Lenz is probably correct, his statistical sampling may be somewhat skewed by the fact that he is working with many manuscripts from close to Lake Constance. 😉 But anyway, until such time as someone comes up with a single example of quire numbering outside the Voynich, I’ll keep on calling that “extremely rare”. 🙂 Looking forward to your next post!

Nick – among the plethora of comment, did you happen to notice the link with post #4?

No need to thank – hope it’s useful.

Diane: if you mean the Chinese missionary stuff, that all came from Jacques Guy in a playful moment, one which he came to somewhat regret later on as a whole bunch of other people produced statistical reasons why it might be correct.

“In re” your comment #12, did Re-ne ever set the Re-cord straight?

%^

Pingback: More comments on quire numbers « Some Voynich ideas

Hello Nick,

mixing up Roman and Arabic numerals is not uncommon in the 15th c. nor is abbreviating Roman numerals in the way the scribe of Beinecke 408 is doing it and it was done haphazard, you should look at some of the everyday production of 15th c. scribes.

I think many people engaged in ‘research’ on Beinecke 408 are overlooking the obvious, that is the reason why they are inventing absurd hypotheses or trying to explore marginalia in every sense of the word.

The obvious thing about Beinecke 408 is that it is a Western European manuscript of about 1410/30. It is very likely that it was written by someone somehow engaged in the medical profession of the time and that it originates from Northern Italy and its content is somehow scientific.

I think Beinecke 408 is a ledger of a student or a young scientist, who was collecting material for his studies, incidentally this would explain much of the strange codicology (has, for example, no researcher ever wondered why Beinecke 408 has no proper binding?) and a lot of other things. I think he was sitting somewhere in a library and making excerpts from medical, pharmaceutical, astronomical and other scientific works of the time, painted his plants and other things and noted quotations from his books.

I took an M.A. in Medieval History and Latin Philology of the Middle Ages (though it was ages ago and I never worked in the field) and I had some intensive training in Latin Palaeography. When I first looked at Beinecke 408 after Yale made the digital copy of the ms. public (I had never heard of it before), my immediate reaction was: scientific ms. first half of the 15th c. (and I have seen lots of mss. in my time). But at first look I could not read more but a few letters and I made the mistake to believe, what everyone else was telling me: It is an unknown script and an unknown language and it is late 15th or 16th c. or even later (I don’t take the hoax theory serious). What worried me was that the cryptographers were not able to do anything about it which for me meant there was something wrong with the basic hyothesis of its being a medieval cypher. But according to the C14 dating it is early 15th c. and when I took another look a few months ago, I soon changed my mind: Beinecke 408 is not a cypher in the sense of the word, it is a ms. which is difficult to read, but you can read it, the script is what you could call a prehumanist Gothic Latin script going in the direction of a cursive script, the language is of course some kind of Latin. The glyphs, which look so strange (and have induced people to make unspeakable transscriptions instead of trying to read the ms., and to invent an obscure alphabet and something like EVA) are Arabic or rather Indian numerals taking turns with Roman numerals and abbreviations. Arabic numerals of the early 15th c. can look very strange to us, they got their modern form around 1480. It seems to me no one has taken the trouble to look up the abbreviations and numerals of Beinecke 408 in Cappelli’s Dizionario, all you need is there (there are at least two copies online). In EVA, U+0072 looks like a 2 to me and U-0073 like a 5, the 9 is a 9, but could be in some cases be the abbreviation, there are two different kinds of 4, one of them should be a Roman 10, an x, aiij is not quoting quire 1, but it is ciiij, very common in the 15th c. for 104 and I could go on. I think the famous gallows are nothing but what we call ‘Siglen’ in German, uniform abbreviatons, and each of these gallows is standing for a work of scholarship as in a modern encyclopedia, for example for the Materia medica of Dioscurides or Petrus Aponensis, de venenis. I think they are derived from litterae oblongatae. There was a school of notaries at Padua at the time with their tradition of abbreviations, but you can see abbreviations similar to Beinecke 408 in early prints as well, there are lots of them online. The transcriptions made for decryption are just nonsense and that is why no cryptographer, no matter what algorithm and computer he is using, is able do do something about Beinecke 408. Incidentally, some of the mathematicians of the 15th c., Giovanni Fontana, Alberti, Toscanelli were at Padua around 1410/30, mostly studying medicine (that is something else no one has taken the trouble of looking up) and since Padua was a small place, they should have met other students, that could explain why someone is using these yet uncommon Arabic numerals.

I have done some very superficial research among the encyclopedias and when I look at the medical profession of the time and at Northern Italy, the first thing that comes to my mind is Padua and its University and its medical faculty, perhaps the most innovative at the time and for the next 150 years. One of the outstanding figures of this faculty around 1410/30 is Giovanni Michele Savonarola, the grandfather of the infamous Florentine Dominican friar. He was a pupil of Galeazzo di Santa Sofia, another important medical man at Padua, who was known f0r his interest in botany and his original approach to the subject. As a medical man Savanarola was of course interested in botany/pharmacy and astronomy/astrology. His list of writings is very interesting. Besides an influential Practica medicinae and some small treatises, one of them De aqua ardenti, he wrote about the medicinal bathing places in Italy, De balneis et thermis naturalibus omnibus Italiae sicque totius orbis proprietatibusque earum and about gynecology, Ad mulieres ferrarienses de regimine pregnantium et noviter natorumque ad septennium. Any similarities with Beinecke 408?

I hope I am giving some people something to think about. I can’t read everything of Beinecke 408 at present and the real difficulty is to find out what treatises the author was quoting and how, but I hope I will find some time in the near future to do some more research, make some transcripts and set up a web site

Helmut Winkler

Helmut: thanks for taking the time to post your thoughts. I (for one) have written and posted plenty of times on Giovanni Fontana, Alberti, Toscanelli, and even Giovanni Michele Savonarola & his book on balneology, basically because the codicology and palaeography has always looks mid-15th century to me. But I have to say that your interpretations of the glyphs conflict with the statistics, your criticism of the (deliberately stroke-based) transcription is missing the point, and your early conclusion that it was necessarily someone engaged in the medical profession is exactly the kind of thing you would criticize others for proposing.

Nick, Mr Winkler, and Ms O’Donovan:

I have been following the B.408 discussion very seriously. I can’t seem to get the point across: One can’t date the document’s script based on the death of the animal that donated its skin. To make my point: I have rabbit skins in moth-ball storage. I know how old the skins are because I raised the rabbits, killed them, skinned them, and tanned the skins — forty years ago. I am now going into my “parchment” storage and I am going to document this discussion. I am then going to let my sons guess when I wrote on that rabbit skin.

BTW, kudos Mr. Winkler! Kudos Ms. O’Donovan! Your research is meticulous and painstaking, and most diplomatic.

Mr. Winkler, I have mentioned on other posts that I am a former pre-med student and have pointed out quite a few of the same features you mention (balneology, women in hot baths, women’s natural cycles/birthing).

I too have mentioned that the notes could very well be those of a doctor’s student/aid/apprentice.

As far as trying to track the path of the document’s journeys: I have also pointed out that several of Rudolph’s relatives lived in Italy and Spain. So, I have yet to see any discussion re those “tips”.

Oscan-Oscian-Volscian. The town/area of Velitrae is still “living”. Athanasius Kircher has also identified the town of Frascati and the villas surrounding the town. Kircher also identified the temple to Praeneste.

So, if Kircher was able to take that manuscript and do a “walkabout” (can’t resist, Diane) and then incorporate those marvels into his treatises, with the prayer “Cherish liber”, why can’t Nick, Rene, Reed et al do the same?

Nick, again I say “Shades of the Blitz Cipher”.

%^

Nick,

Not sure if this is helpful, but here’s an odd little German manuscript (Kalendar) which appears to use margin writing to teach the Latin names of both roman and Arabic numbers. The abbreviations are a bit odd, but are not identical to the VMs.

Note that it also contains the illusive Sagittarius crossbow archer.

http://diglib.hab.de/wdb.php?dir=inkunabeln/1189-helmst-2&image=00002

Nick, others:

You really should take a good look at Tim’s referred link. It is not just an ordinary calendar. It appears, to me, to show translations of at least three dialects to Latin. It also pictorially refers to Saints Days in each 30-day segment. The illustrations are quite similar to the astrological section of the Vms.

The thirty-day segments are pictorially linked to the rural farming practices/activities.

Fabulous!

For some time I have a hypothesis that perhaps Voynich may be written in Judeo-Italian language. All is based on one image

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:CursiveWritingHebrew.png

specifically columns 10 & 11, which bear some resemblance to Voynich manuscript. Following the hypothesis I found that there were quite a few dialects that are almost extinct by now, and that official Hebrew script differs from the manuscripts written for non-official purposes.

Sadly I wasn’t able to find any manuscripts written in these, though there does exist some.

I am no scholar and have neither time nor patience to research this. Neither is my Engrish good enough for official documents.

Links for reference:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cursive_Hebrew

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=1308&letter=A#3547

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/index.html?curid=761021

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judaeo-Spanish

http://www.jmth.gr/web/thejews/pages/pages/judeo.htm

If this reference might help (and you find pages 79-81) you may find the closest match to Voynichese lettering I’ve found yet:

I can’t make the link, but here is the title of the webpage:

The Scriptorium and Library at Monte Cassino, 1058-1105. By Francis Newton

The example shows the evolution of the scribes linking/combining letters. Also, this is the ONLY manuscript I’ve found that uses the “ampersand-like” character. This is also the only Ms that I’ve found, so far, that uses the backward “S” that I call the “sickle” shape (crescent with an attached “handle”.

If only I were able to download!

%^

There’s a constant confusion here between the date and place of the object’s manufacture (inscription on the membrane, formation in quires and/or binding), and the date(s) and place(s) for first and later enunciation of the matter inscribed and drawn.

The standing archer for Sagittarius is not a German creation, any more than the rippled band known by the German term volkenband. The first derives from the pre-Roman and non-Roman astronomical traditions; the second from Persia.

Finding the examples in later northern manuscripts tells us little except that the habit was adopted pretty late in those regions. Where it appears as a “warrior” it is not only a late image but a corrupt one, since the figure is correctly a hunter.

before Gallus, Bobbio

My “map” analysis takes the author’ journey slap bang through Fribourg, but this could easily be incidental.

Diane wrote: “The standing archer for Sagittarius is not a German creation, any more than the rippled band known by the German term volkenband. The first derives from the pre-Roman and non-Roman astronomical traditions; the second from Persia.”

Herbal illustrative traditions originated in the eastern Mediterranean. That doesn’t mean all 15th-century herbal manuscripts were copied from the early Mediterranean versions.

Many were copies of copies of copies that originated far from their origins. Where something originates and where it was copied are two different things and each copy mutates slightly due to errors or deliberate localization (e.g., English plants and English clothes were gradually added to English herbals copied from copies of Mediterranean manuscripts).

.

By the late 1300s, a standing archer was a germanic creation. Many of the copyists had no knowledge of its ancient origins, just as those who watch romantic dramas on YouTube aren’t familiar with the (pre-Shakespearean) origins of Romeo and Juliet. They are presented and understood through a contemporary context.

Southern and Middle Eastern regions preferred Sagittarius as a centaur in the Middle Ages.

JKP

para 1 – true

para 2 – of course it doesn’t. Go deeper.

para 3 – your wiki source isn’t wrong, but your inferences are.

para 4 – no.

para 5 – not exactly.

What you forgot was to think, and to question – and not to question me (‘What leads you to think so?’) but yourself (‘What have I assumed? Are these assumptions justified by the balance of evidence? ).