A journalist contacted me this week to ask me about poor Ricky McCormick’s cryptic writing. I hadn’t written anything about this since 2013 and 2016, and even the Riverfront Times’ 2012 “Code Dead” article was now only in the Wayback Machine. An update was long overdue…

“Meet Me In St Louis, Louis…

…Meet me at the fair“. Do you know the song?

All the pieces of Ricky McCormick’s life were held together by the gravitational pull of downtown St Louis. It was where he grew up and went to school (sometimes), it was where he worked (sometimes) and travelled around on the buses, it was how he talked, it was where he lived (and indeed died). In my mind, the puzzle of Ricky McCormick’s notes (here and here) is likely to be not so much a code-breaking one as a geographical and linguistic one.

If we could only find a way to meet him in St Louis, we might stand a chance of reading (or at least reading through) his notes. To be brutally honest, I doubt that decrypting these will throw much light on his life (never mind his death), but his notes remain a puzzle, and one with its own gravitational pull.

Ricky McCormick’s notes

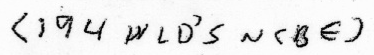

The distinctive series of letters “WLDNCBE” appears eight times in his notes: but so too does the same series with an apostrophe, i.e. “WLD’S NCBE“:

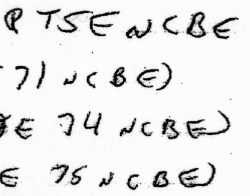

So it seems likely that this “WLD’S NCBE” is the full version of the phrase, and “WLDNCBE” is the quick version. Both WLD and NCBE also occurs lots of other times, with the latter often preceded by a number:

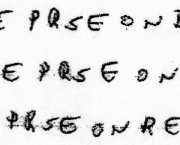

“PRSEON” is another common pattern, which I’ve long suspected could mean “person”:

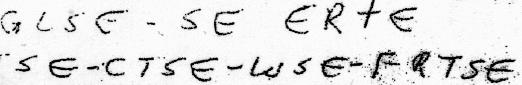

Even just “SE” is something that appears a lot more frequently than you might normally expect:

McCormick also seems to use “XL” as a common pattern, so perhaps this was a phrase he liked? And there’s one word in there that looks a lot like a jumbled version of “special”:

There’s also something that looks like “MR DE LUSE”, though who that was remains unknown:

If not at the fair, then where?

Looking at Ricky McCormick’s notes, you can see plenty of short number groups (71, 74, 75, 194, 26, 35, 651, 74, 29, 99.84.52, 3, 1/2), plenty of letters, and plenty of word-like letter structure. It might therefore seem reasonable to conjecture that these might possibly be references to places in and around St Louis, all rendered in his own idiosyncratic (and very possibly dyslexic) style, and so effectively a private language only readable by him.

But… American street addresses don’t in general work like this at all (and certainly not in downtown St Louis). So if these are addresses, I think it’s highly likely that they’re for a specific neighbourhood with lots of adjacent-numbered flats. The most famous high-density living area in St Louis was the post-war Pruitt-Igoe high-rises: yet the last was demolished in 1976 (the site remains largely vacant). In fact, you may have seen footage of this without realising it, because some appeared in the (1982) film Koyaanisqatsi. So I’m kind of out of ideas here as to where these even might be.

All in all, I suspect it will take someone with a grasp of the sociogeography of downtown St Louis far better than me (along with a far better grasp of McCormick’s spoken accent) to come up with any candidate places. I’ve trawled Google Maps plenty of times and yet my net has always come up empty.

What do you think, Nick?

Pfffft… even in 2013 I wrote that “quite unlike other cipher mysteries, I don’t actually want to read what was written on McCormick’s two notes“: and I am, alas, still bobbing along in that same boat.

Still, it was nice to have an excuse to put up a blog post with a picture of Judy Garland, eh?

Might some of the numbers be referring to St Louis bus route numbers? As of 2024, these are almost entirely in the 1-100 range:

https://moovitapp.com/index/en/public_transit-lines-St_Louis_MO-1343-11008

What the St Louis bus numbers were back in June 1999, I have no idea.

the language seems to cling to a form of typing words like T9…years ago, when the text appeared in the international press, I saw a resemblance while playing on the keyboard of a telephone and trying to form words….someone told me that in those years when they discovered the notes, that language didn’t exist on mobile phones, or Ricky didn’t have a mobile phone or maybe he used a fixed street phone….it’s just an idea that gives me the feeling that this would be the solution

Hi Nick,

Thank you for this update, and this case has always interested me.

The RiverFront Times article still seems to be the best and fullest account of this case. It doesn’t look as though anything much new has come to light since. But transcriptions of the notes are now available online, so I thought I’d try some very basic letter frequency analysis of the notes. The first number shows how many times each letter occurs in the note headed ‘P1’, and the second gives the instances of each letter in the note with ‘NOTES’ printed at the top:

A=5/6

B=19/9

C=27/18

D=17/12

E=60/71

F=10/1

G=3/4

H=1/4

I=6/0

J=0/0

K=4/9

L=24/27

M=11/19

N=48/42

O=7/6

P=17/12

Q=0/0

R=36/36

S=39/62

T=17/22

U=4/11

V=0/1

W=9/7

X=4/7

Y=2/0

Z=0/0

What strikes me here is that the most common consonants in the notes are, by and large, also the most ones found in standard written English.

TNRSH DLFCM GYPWB VKJXZQ (frequency sequence for consonants in written English)

SNRLC TMDPB WKFXG HYVJZQ (frequency sequence for consonants in the notes)

It isn’t a perfect match, but it’s suggestively close. Eight out of the ten most common consonants are the same, and four of the six least common consonants are also the same.

But with the vowels, things are very different.

ETAON RISHD LFCMU GYPWB VKJXZQ (complete frequency sequence for written English)

ESNRL CTMDP BWUKO FXAGI HYVJZQ (complete frequency sequence for the notes)

The only vowel used frequently in the notes is E. It is the commonest letter both there and also in written English. But, while they are some of the most common letters in written English, A, I and O are inexplicably rare in the notes, where X is equally common as A and more common than I.

I don’t have any good suggestions for why any of this is so. You might get this kind of frequency pattern if the notes were a heavily abbreviated consonantal skeleton of normal English words, from which the writer stripped out as many vowels as possible and then used E’s to mark ends of words. And that might then explain why ‘words’ in the notes seem fairly short, and why lots end SE (plurals ending in S, with an E to follow)? I’m not saying for a moment this is necessarily right, and there must be other possible explanations too, but…what do you think?

Hi Nick,

I refer to the end of p1 and start of P2

(FLRSE PRSE ONDE 71 NCBE)

(CDNSE PRSE ONSDE 74 NCBE)

(PRTSE PRSE ONREDE 75 NCBE)

(TF NRCMSP SOLE MRDE LUSE TO TE WLD N WLD NCBE)

(194 WLD’S NCBE) (TRFXL)

Page. 2

ALPNTE GLSE – SE ERtE

VLSE MTSE-CTSE-WSE-FRTSE

PNRTRSE ON PRSE WLD NCBE

The conjecture has been made that the start of line FLRSE PRSE ONSDE can be read as FIRST PERSON DE etc

I have a counter example that would seem to reduce the possibility of PERSON as an interpretation (ignoring use of anagrams)

That counter example is page two line three – the last line in the block quoted above and is..

PNRTRSE ON PRSE WLD NCBE

Observe this time ON and PRSE are the other way around.

I think this line would also go beside the lines inc 71, 74 & 75 and be compared with these three lines, but I won’t pursue that for now.

Hi Nick,

I was considering seriously making a go at cracking the three lines inc numbers 71 74 and 75.

As an aside, without intending to pursue the matter now, I am considering that regarding these three lines, the previous line again might amount to column headers for the subsequent three lines.

However, I decided this was still too opaque and I want to proceed from the known to unknown.

Significant observation.

Page 2, line 6 (being the first line in block two encircled by borders)

Which is – compared to photograph

(M U N S A R S T E /N/ M U N A R S E)

Where the first R is badly written and could be an I but isn’t.

I am taking the liberty of using /N/ to separate into left and right portions.

The right side ie munarse including the final SE anagrams to SURNAME.

Consequently we must also question the hypothesis of E or SE being separators as SE constitute parts of surname – specifically initial and terminal character.

The left side also anagrams to SURNAME also but with insert d stay characters the significance of which isn’t yet clear but almost certainly is significant.

I represent the rewriting of this line as follows (leaving the insert * characters where they were) …..

(S U R S* N A M T* E/ N / S U R N A M E )

I think this might be a significant step forward but requires much excessive cogitation to see where it goes.

Looking to the future, I have in pen and ink followed the same procedure for Page 1, Line 1 neglecting the (ACSM) and also get the word SURNAME on the left hand side – specifically ….it becomes ….

M N D / S U* R N A* M E/ E – N – S – M – K N A R E ) ( ACMS)

Notes U* The first K in the photograph is plausibly a I

Notes A* The A is badly written as A over a T

Also – ambiguity – there are two Es – I picked on one the left hand side first, if I remember correctly, when doing the anagram – I have no longer enough brain cells still awake to work out what happens if I used the Es in a different order

I should point out this is not what I expected and is due to the transcription of a K as a U on looking at the photograph.

Also, I have made no progress on the right hand KNARE or the four characters at the end.

I went into this expecting something like Mcnare N Mcnare.

Correction

Notes U* The first K in the photograph is plausibly a I

Should read

Notes U* The first K in the photograph is plausibly a U

Apologies

I have now looked at page 1, line 2 again and rewrite it as (with provisions)

(MND/SKRNAME/E N SKRNAME) (ACMS)

First the Ks look like Us and it is debatable.

Further cogitation required – the little grey cells need to work away by themselves to see where this takes the story.

Nick. That’s not the number 7. The correct reading is number 1. ( 11.14.15.)

11 months in prison.

14 was old Pretty.

15 miles from where he lived. (found dead).

Other. The word you are reading is “Person”. Correctly read ” PRISON “.

The words are English and German. The text is about death.

Signs that repeat several times. Which one are you reading NCBE. Also read iCBE.

(the sign is variable). It can be read as the letter – i, or the letter N. When the numerical value of the letters is taken, the result is 11 or 15.

(iCBE = 1+3+2+5 = 11). (NCBE = 5+3+2+5 = 15).

Part of the text ……TOTE WLDi WLDi CB E ).

Tote is German = dead. Ricky died when he was 41 years old. Numerical value of letters – iDLW = 14. ( iDLW = 1436).

The letter E is sometimes used as a deceptive sign. The letter B ( CB ) has the number value 2. The entire series of letters BRK has the number value 2. So the letter B can be read as R. ( CR = Cormic Ricky ).

The sentence is read from right to left. R. C. 41, 41 Tot.

Ricky Cormic died when he was 41 years old.

(his mother: All he could write was his name. He didn’t write in any code).

So it was written by someone who helped him for eternity.

(interestingly, he was born on the 14th and died on the 14th).

This sentence is interesting. Joined from two that are in parentheses.

Cons prison sat 14, Pretty see prison redy 15.

That means He went to prison because Pretty was 14 years old. It would be fine if she was 15.

( iCBE = 1325 = 11….NCBE =5325 = 15 ).

@SirHubert – It’s an interesting observation, but I suspect fairly easy to explain. Someone who struggles with the English language likely struggles (even to write) to properly identify vowel sounds. Given this seems to be a shorthand that largely drops vowel sounds, it sort of seems reasonable that where they’re explicit they’re not entirely correct.

Many moons ago I worked in a role that included name matching and identity resolution. Some of what we did involved romanization of names from Chinese and Arabic backgrounds. There are different methods of doing this, but basically the same name might be “romanized” differently by different people – so the same name might be spelt Xhang, Xang, Xiang, Zhang, Chang, Zheng, Cheng…..etc. Similarly Arabic names weren’t always consistently translated (there were about 32 variants of Mohammad and a similar number of Mahmoud). The Mohammad variations include changes in vowel-sound (e.g. Muhamed).

Obviously we’re not talking about names here, but the point is it’s a result of trying to phoneticise unfamiliar words.

On a different tack, NP’s original bus-related ideas had me wondering whether rather than the 3 similar entries being people Ricky was supposed to meet or interact with, whether they might be people he observed – perhaps getting off different buses. The NCBE might identify the location he’s at (e.g Northern Corner Bus Exchange – or something more phonetic), the numbers are the bus someone boarded or alighted (NB: Not sure if 2nd one is 74 or 34)., the prefix to those numbers perhaps identifying a specific zone (it’s worth noting that after PRSE ON (space deliberate) we have DE then SDE then REDE – so an evolution to more letters/detail).

I really, really DON’T like the idea of FIRST, SECOND, THIRD. – the 2nd Char in line one looks more like an L, and PRtSE doesn’t even remotely resemble THIRD.

This is all just throwing ideas – I haven’t thought it through much, and _IF_ the word person is represented (not entirely convinced) I’d suggest PRSE represents it rather than the entire PRSEON…..

But like anyone, I’m a little lost on it all, and anything that seems to make sense one minute is rendered crazy the next….

MRDE LUSE = murderer loose?

Oh very last line D.W.M.Y = day week month year