I thought it would be a good idea to try to draw up a list of the Voynich Manuscript’s male zodiac nymphs, as a dataset that might be useful when attempting to map between zodiac nymphs and feast days. And yet if you try to do this, it turns out to be really hard, because… what are we looking for, exactly? As the following image from f70v2 should make clear, is the absence of clearly delineated breasts really enough?

Also, if you hope to visually read the nymphs’ red lips as if they were (emblematically female) lipstick, this too is more than a touch problematic. From reading Caterina Sforza’s Gli Experimenti, I recall recipes for hair bleaching/colouring, face whitening, hand cream and rouge for the cheeks, but nothing for lipstick. In fact, lipstick seems to have played no great role in the fifteenth century: cosmetic historians tend to fast-forward to Queen Elizabeth I, who is said to have painted her lips excessively red (some have even theorised that a toxic layer of lipstick led to her demise).

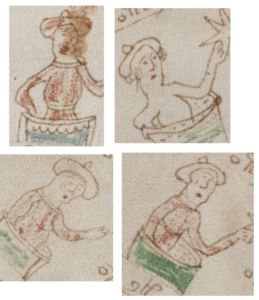

Other nymphs appear to have male, uh, features, but this is often a result of how long you stare at them. The scans are good, but they’re far from definitive, let’s say. Meet the particular Gemini nymph I have in mind here:

As a result, I ended up spending a good amount of time looking at all the zodiac nymphs under the (virtual) microscope. (I used Jason Davies’ “Voynich Manuscript Voyager”, because the printing in the various facsimile editions I have wasn’t good enough to do this.) Which was when I found the Aries hats…

The Aries hats

Starting with Aries, the page layout changes format from 30 nymphs per page to 15 per page. This is accompanied by a change in style, where the drawings are slightly more detailed. This change continues through Taurus, but then flips back to 30 nymphs per page for the remainder of the zodiac.

What I found interesting was that “light Aries” (the second set of 15 zodiac nymphs for Aries) has a number of zodiac nymphs with a distinctive head-dress.

Though there are more hats on the page which follows (Taurus), only one of those has the same distinctive “bobble” on the top, and that is atop a (I think quite different) hat which is far more akin to a turban, AKA chaperon. (You can see mid-15th century chaperons here and here. And maybe here.)

So… what is this hat, then?

Is the thing on top a pom-pom? If not, then what?

The bobble on top seems far too small to be a fitted cap, so I think we can rule out hat styles like the galero. It seems to be a decorative style rather a practical style: or might it be a small peak on top, like a much smaller version of the truncated cones seen in some mid-fifteenth century hennins. Maybe it’s a pom-pom, but I have my doubts. (Plenty of them)

And having now trawled miserably through several thousand fifteenth century images looking for similar hats, I have found not a single one, and I have to admit defeat. Even the useful set of headdresses courtesy of Susan Reeds’ thesis is of no obvious help to us here, while Sophie Stitches has a good page of sources that also doesn’t seem to help. If it’s a kind of flat hat, Susan Reeds notes that “[a]s with cauls and sugarloaf hats, flat hats were worn mostly by men in the gentry or courtier/professional/official classes“.

So… what is this hat? My general feeling is that it must be a kind of hat that was probably unique to a particular time (perhaps no longer than a decade) and a particular place. Whoever finds when and where might well make a significant step forward here. But it doesn’t feel like that person is going to be me.

Diebold Lauber manuscripts

Finally, I had a good look through a number of Diebold Lauber manuscripts, but found only fragmentary matches, such as these from Cod Pal Germ 314:

(Last one from f49v).

Cod Pal germ 137 was equally unimpressive, with only a few knots on top of hats that are more in line with what are known as “acorns”:

Feel free to do much, much better than me in the hunt for this hat…

Dare I say it, but I think those in the bottom set of Voynich images are foreshadowing Steeleye Span by a few centuries!

According to Wikipedia in one version of the traditional folk song, the young man is a street hawker who is mourning his separation from his lover who has been transported to Australia … where she realised that there were plenty of other fish in the sea: flathead, leatherjacket – you know the type!

NickP … you know it, I know it, this wordy pursuit of a badly drawn and innocuous bobble is just an attempt by you to post something other than what is about to be revealed in South Australia.

I share the tension.

Peteb: even once we’ve heard SA police’s much delayed announcement, it’s still entirely possible we’ll know more about the bobble than the Somerton Man. 😬

Nick –

Is there a separate caption for the last of your examples from Cod Pal germ 137? It’s unlike the rest.

For the others – knitted and crocheted hats typically end like that. Knitted fabric began as an offshoot of net-making, and early examples have been found, but I’d guess crochet for most of the examples, knitting in Europe taking off among the city populations, I think, only from about the 16th-17thC. I can’t check it, though. I no longer have my copy of Agnes Geijer’s brilliant study.

Sorry – I should have said “Is there separate caption for the last example from *Cod Pal Germ 314*”

For your examples from Cod Pal germ 137, the fifteenth century is a bit early for needle-made fabrics, now I think about it. Irresponsible to guess when specialist studies – archaeological- and conservation reports supplementing histories of costume – will serve you better.

Without the pom-pom, those look like some kind of chaperon.

If I forget for a moment how bad is the Voynich Author at painting, I can say that I found a couple of pictures showing some headgear similiar to that.

One is the man at the centre of the Battaglia di San Romano by Paolo Uccello, who is wearing a mazzocchio with a distinct little ball at the top.

Another one is the man with the turban in a print depicting the meeting between Charles the Bold and Frederick III.

[1] https://www.uffizi.it/opere/battaglia-di-san-romano

[2] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/90/166Friedrich_III_und_Karl_von_Burgund.jpg

Bobbles appear several times in this manuscript Nick. Noticing the clothing style is in f.82r below is much like the voynich archer. I linked all the bobbles to save anyone interested time.

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/zbs/SII-0043

Country of Location: Switzerland

Location: Solothurn

Library / Collection: Zentralbibliothek

Shelfmark: Cod. S II 43

Manuscript Title: “Historienbibel” from the workshop of Diebold Lauber (‘vom Staal-Story Bible’)

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/zbs/SII-0043/72v

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/zbs/SII-0043/82r

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/zbs/SII-0043/107r

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/zbs/SII-0043/116r

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/zbs/SII-0043/131v

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/zbs/SII-0043/252v

Steve: thanks, a very interesting Diebold Lauber manuscript bible (I checked through all the Cod Pal germ bibles, didn’t find anything interesting there)! Given that it seems to have been commissioned by the town clerk in Solothurn, I can’t help but wonder whether the distinctive hat might actually be a cultural nod from the artist(s) to him. The dial’s not at 100% yet, but it’s definitely a good lead to follow, thanks!

Stefano Guidoni: I’d say some of the headwear on the Taurus page is very much like a chaperon (one of which seems to have a pom-pom), but the Aries hats seem somewhat less extravagant and layered.

Uccello’s mazzocchio headwear is cool, though given that it is basically a torus, it would superficially seem to be a type of roundelle (as described by Susan Reeds) without a top ‘cap’ part (as per the three dark mazzocchio headwear instances in the Battaglia di San Romano painting). This makes the presence of a golden pom-pom on the top of the spiral roundelle headwear in the middle somewhat mystifying. In Uccello’s “Flood” fresco, the mazzocchio is around someone’s neck (though perhaps with a feather coming up from behind the wearer’s head?), so is definitely more like a cap-less roundelle.

Peteb: of course you’re right, it’s part of a drawn out series of diversions away from more important relevant issues that NP would rather distance himself from just now. Stands out like a top tasseled coif of olden times…or bulldogs balls, take your pick!

Worth considering?

The Voynich Manuscript, Dr Johannes Hartlieb and the Encipherment of Women’s Secrets Get access Arrow

Keagan Brewer, Michelle L Lewis

Social History of Medicine, hkad099, https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hkad099

Published: 22 March 2024

marble bust. ‘Pythagoras of Samos’. Rome. Coliseum, 2ndC – 1stC BC.

(British LIbrary’s digitised mss – still down.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turban#/media/File:Pythagoras_in_the_Roman_Forum,_Colosseum.jpg

@Steve

What you call a hat with a bobble is a Jewish hat. This cannot be seen in the VM.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judenhut

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_hat

What you see is something like a priest’s cap or beret with a ball.

You can recognise some in this picture.

https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=2229143957308246&set=pcb.1970377369738721

Priest’s cap in the original and in the picture (1350)

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1997124463843531&set=g.504064963036643

https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=1997124063843571&set=g.504064963036643

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1997121997177111&set=g.504064963036643

The mazzocchio is, properly, the torus or roundel, however it was used as a part of the Italian chaperon, especially in Florence. As such it was usually covered with fabric. Example:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9e/Florentine_15th_or_16th_Century%2C_probably_after_a_model_by_Andrea_del_Verrocchio_and_Orsino_Benintendi%2C_Lorenzo_de%27_Medici%2C_1478-1521%2C_NGA_12189.jpg

The pointed hats of that Diebold Lauber’s Bible are Jewish hats. There are many different kinds of Jewish pointed hats, but I could not find any with a large roundel or turban like those of the Voynich.

Well, unless those are not roundels or wrapped fabric, but large brims seen from below. However I think that would be a very strange pictorial choice, unusual and confusing, a mixture of bad perspective and poor style.

The other is a chaperone (bound).

Philip of Burgundy has often been depicted like this.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philipp_III._(Burgund)

Lauber has a nice example here (link).

https://www.voynich.ninja/thread-4173-post-57902.html#pid57902

https://www.voynich.ninja/thread-4173-post-57901.html#pid57901

@Peter M.

Thank you, Peter.

I’m not sure how to ask this question without sparking indignation but it is an honest one.

Is the aim of this conversation to discover where, and by whom, headwear like that shown – well or badly – on the calendar-figures, or is it to support an argument made by Koen Gheuens that the Voynich calendar, or some part of it, is connected with Diebold Lauber’s workshop?

If the aim is to find ways to further a ‘Lauber workshop’ theory, I can understand why no-one seems to be looking further. Nick’s example from folio 49v in Cod Pal Germ 314 is certainly impressive – but what sort of person is identified by a hat of that type?

If, however, the aim is to investigate questions raised by the manuscript itself, why such an extraordinarily narrow range of sources?

By the 15thC, European males were wearing a wide variety of headwear and in Italy and in France, at least, it was quite the fashion to sport a hat designed in an antique or an exotic style. You see versions of the Turkish fez, of the turban, and in the following link, what is said to be a hat worn by a French army officer, an which is plainly modelled on Russian and more exactly on Mongol style – except made of velvet, and adorned with pearls, and according to the drawing’s caption.

(The drawing comes from a well-respected English history of costume).

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/24/e1/87/24e187c0c0858e6c75e5b086e4dc82d8.jpg

It’s worth keeping in mind, too that the Voynich figures are very small, and from brow to top, the headwear measures between one millimeter and two millimeters.

We can’t expect superhuman hand-eye co-ordination, and a tiny, roundish detail *might* be meant as a pom-pom, or as the crown of the head, or the slightly pointed end of a piece of fabric. Or a pom-pom.

There are many books at internet archive on the history of dress, but some are only meant to help fancy-dress parties, or as guides to theatricals. Some of the nineteenth-century ones look good, but filled with historical errors, romanticism and so on. Best to ask the conservation department of your nearest museum for the names of current standard references if your aim is to research these drawings.

Peteb: ‘follow my leader’ never fails, they can’t resist!

@Diane

You write “Nick’s example from folio 49v in Cod Pal Germ 314 is certainly impressive – but what kind of person can be recognised by such a hat?”

It’s a priest and a king.

The text begins with the words “One reads of a priest”. “Man liest von einem Pfaffen”.

Here he is giving the king something of a moral sermon.

It is large and drawn accurately enough to be easily recognisable.

The one example I have shown by chance is a stove tile from 1380, which was so fashionable. But it was ridiculous.

The fact that Koen’s example of the VM twins is so similar to Lauber’s twins is certainly no coincidence.

Lauber was a copy workshop. He mainly copied the books. Perhaps compiled and rewritten, but not written. (first author)

There must be more that is similar.

The examples Nick has listed. (4 books) are a prime example of copying, so to speak.

Then there is the headgear of the surgeons of the time. Not exactly a ball, but the one that looks like it has a thread.

But you can’t see it in the VM.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jacobus_Berengarius_Anatomia_carpi_Titelholzschnitt_1535_(Isny).jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jacobus_Berengarius_Anatomia_carpi_Titelholzschnitt_1535_(Isny).jpg

Better to see here. Gown of medicine.

“Mondino dei Luzzi”

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/xwqcpd4w

And the last one is probably a Jewish cap.

Here you can see both at the same time. Hat and cap.

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/de/zbz/C0005/34r

Are you going to comment on:

https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=63603

Once again the Voynich manuscript

and

The Voynich Manuscript, Dr Johannes Hartlieb and the Encipherment of Women’s Secrets, by Keagan Brewer and Michelle L Lewis, Social History of Medicine, hkad099 (22 March 2024)

and

https://theconversation.com/for-600-years-the-voynich-manuscript-has-remained-a-mystery-now-we-think-its-partly-about-sex-227157

?

Nick,

That the styles of headwear change between one and another of those diagrams seems to me a significant new observation.

Peter M.,

In Koen’s blogpost of Sept. 2nd., 2018 where he treated the twins, he cited an image that I found most interesting. It comes from a fifteenth-century manuscript which copies the oldest available sources – including some credited to Eratosthenes.

3)22v (l. 15)-23r: Eratosthenes, ( c. 276 BC – c. 195/194 BC), the work composed c. 284-194BC ‘ De circa exornatione stellarum et ethymologia de quibus videntur’.

About the hats, though – you might know that in western medieval art, when everyone isn’t dressed Latin-style no matter where they’re supposed to be from, hats are used to indicate status, culture and character. For an easy example look at that now well-known frontispiece to Oresme’s work – a contribution to the study made by Ellie Velinska, reviewed here by Nick. Ellie’s blog is now closed from the public.

Band plus (k)nobby bits

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/fd/2c/07/fd2c07a271838ea4e3fcc04a9a2b83e8.jpg

@Diane

I understand you.

So a picture of Nick shows a helmet rather than a cap or hat.

Maybe it’s because he’s wearing something like a spear on his shoulder. Things like that influence the view. That’s why it’s always good to have several examples.

Looking at it this way, a cap can mean more.

Swiss shepherd’s cap.

https://www.toesstaldesign.ch/Swissness/Sennenkaeppi-Cap/

The Pope somehow has the same.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pileolus

That’s not surprising. Somehow he too is just a shepherd looking after his sheep.

Or why is the crozier actually a shepherd’s tool? Shepherd’s crook.

Peter M.

There’s a huge range of possibilities for the skull-cap. Our difficulty is to check that our ideas aren’t anachronistic, and to attempt to describe what was in the original draughtsman’s mind, rather than our own. Not easy, is it?

Sometimes it is really difficult to authenticate something.

In this link, the person on the right. What is she holding in her hand?

https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/de/zbz/C0005/185r/0/

Without reading the text, I would guess a fish.

But it’s not. The text says exactly what it is.

@Peter

Without reading the text I’d say it is a mandible. There are teeth on it.

@Stefano

That is correct. It’s the lower jaw of a donkey.

He writes ‘ Here Samson of Judea is arguing with a donkey’s lower jaw’… ‘chin + cheeks’.

“Hier streitet Samson von Judea mit einem Esel’s Unterkiefer” “Kinn + Backen”

Judges 15: 15-16.

The figure is Samson in pre-Delilah days.

@Peter

Now, after you told me that, I can literally read:

“Hie strit Sambson von Judea mit eins esels Kinbacken.S”

So, I suppose:

Hie = Hier

strit = ???

Sambson=Samson

eins = eines

Kinbacken = Kinnbacken

“Here Samson from Judea [does something] with the mandibles of one donkey.”

Anyway, I get that your theory here is that those hats are some kind of Canterbury caps or medieval “biretta”.

Looking for “medieval birettum” on Google, I literally found this:

https://textilverkstad.se/pdf/biretta_eng.pdf

@Stefano

“strit”alemann / dt. “Streit” comes from ‘dispute’.

As for the cap, there are plenty of representations. Even the Scots have one. But I don’t know from which century it was worn.

The original I have shown is a museum piece.

@ Stephen Goranson — re your comment of April 22, 2024.

You may be wondering why there’s so little reaction to your reference to the item by Keagan Brewer and Michelle L Lewis.

I expect it’s partly because some of the speculations are so old and partly because some of the speculations are so pleasing to persons determined to promote a ‘post-1440 Germanist’ storyline.

The old speculations have been adopted uncritically from William Romaine Newbold’s subjective impressions in the 1920s, just as they passed without investigation for the following century. They weren’t only not rejected for the most part, but never so much as cross-examined. The only one which was immediately rejected was the ‘biological-anatomical’ notion. Not that anyone listened, and when Sergio Toresella picked up again on the ‘women-sex-medicine’ speculations, no-one was so impolite to behave as the editor of Scientific American had been in the 1920s.

Why these authors should have decide to combine those old notions – without bothering to test them – with an inherently anachronistic ‘ Johannes Hartlieb’ theory I can’t imagine.

The very best you could say was that, IF all the content now in the manuscript had been first given form when our present manuscript was made and IF you completely ignore the fact that 1440 is, by all normal criteria, the latest date for the present artefact and pretend that at the age of 18 Hartleib could have been a specialist in women’s medicine and (despite being educated in the extremely conservative region of Bavaria) could have filled the pages of his notebook with unclothed female figures drawn in a style entirely unlike that of early fifteenth century Bavarian work, then there might be something to be said in favour of a genuine link … that is a genuine historical link, rather than a wholly imaginative one… between Hartleib and Yale, Beinecke MS 408.

By 1440 the only work which Hartleib can be connected with is a compendium of herbs. His translation of the Sicilian Trotula and ‘women’s secrets’ was not produced until the later 1450s, and the copy now is a copy made late in the sixteenth century – c.1570. (Heidelberg, Cod. Pal. germ. 480).

The publishing editors know whom they chose as peer reviewers for the manuscript. What led them to choose the reviewers they did I won’t try to speculate. Of course I’ll read it through – but the reviews you’ve linked to don’t inspire confidence in much except a dreary certainty that the ‘Toresellla-Germanist’ camp will start citing the authors as ‘academic authorities’ and the book as ‘scientific’.

I’d like to see them try to persuade the Louvre or the British Museum that the manuscript is a mid-fifteenth century Bavarian product.

Red lips, with or without red / pink cheeks etc. are part of the medieval technique of adding color to human faces. It’s not a promotion for cosmetics. French manuscript examples go back at least to the early 13th century.

A couple of 15th century examples show the variety and a certain proximity.

UB Freiburg Hs.334 [1410, Alsace. A picture Bible]

UBH Cod. Pal. germ. 359 [1418, Strasbourg. “Rosengarten zu Worms”]

@o.o.t.b.

..and it is an established convention of Spanish-Christian examples for centuries before that. I looked into the question a fair while ago, when investigating the elongated ascenders and again when tracking the history of ‘Arcitenens’ as distinct from ‘Saggitarius’ as image for that constellation. If it will be of use to you, I’ll go back and find some of the examples I cited from.. what.. the 11th and 12th centuries?

Sorry to sound as if I’ve been there and done that, but it’s possible to cover a lot of ground researching one, and then another question for more than a decade.

It is an artistic technique, and it can easily become embedded in culture. I like to stay between 1400-1450 as much as possible. I don’t see how historical Spanish art had a real influence of the production of the Alsace and Strasbourg mss.

The investigation of red lips is just another of the details to be found in the VMs. It is inclusive of the C-14 dating, but it is not particularly definitive. The VMs artist is rather minimalist and quite consistent in the application of this technique. In the Lauber productions, some texts are more consistent than others.

It all goes together – eventually – to show that the VMs artist had a surprising familiarity with historical realities based in the first half of the 15th century. From cosmic diagrams, to Melusine, to sleeves and hats, etc. the artist plays off of this knowledge to combine with Shirakatsi’s wheel or the FIeschi popes and heraldic canting. The use of dualistic representation is an indicator of intentional artistic trickery.

Without the history to back up the interpretation, there is no understanding what the VMs artist actually knew. With the historical focus on the C-14 era, this knowledge is being recognized in several VMs illustrations [e.g.: f46v costmary.]

ootb

I should like to see the codicological and palaeographic argument for the manuscript’s being attributed to Alsace Lorraine. Can you point me to an essay of that kind?

I am bewildered by assertions, or presumptions that the Voynich manuscript’s drawings are the creation of a single fifteenth-century ‘artist’, and all the more if that imagined ‘artist’ is imagined a medieval Latin in western Europe. There is no figure of Melusine in the Voynich manuscript; there are no stave-built barrels, either. Nor is there any figure wearing the tall headdress in which she is usually shown. The ‘Melusine’ idea is yet another of those which results from back-to-front research. Instead of asking – and exerting oneself to discover – what those who first created the drawing intended it to mean, the old way is to make a guess that the person was this or that, then to proceed by saying, in effect ‘Assuming my guess is right, then what’s the nearest fit within the limits of my speculation’ and the ‘nearest’ found to this figure within the old speculations is Melusine. Yet when you actually consider fifteenth-century Latin manuscript images of Melusine, none remotely resembles the style and presentation of any ‘Melusine image’. Then that obvious disparity is glossed over by attributing to some imagined fifteenth century ‘artist’ not only an appallingly poor ability as an ‘artist’ but the freedom to draw in any way that s/he felt like drawing – a massive anachronism. The notion of using drawings as a means of self-expression, let alone abandoning all the conventions which applies, is a fantasy – an imposition of post-19th century ideas about the ‘artist’ and the role of ‘art’ upon a time and region which had no concept of such things. I understand few have the time or interest to learn much about the history of art, or about how we distinguish iconography from one region and period from another, but I do wish it were possible to encourage more interest in such things, particularly when almost all the speculative and quasi-historical Voynich stories rely so very heavily on making assertions about the drawings. Yet when you actually consider fifteenth-century Latin manuscript images of Melusine, none remotely resembles the style and presentation of any image in the Vms.

@Diane

I completely agree with you. No Melusine in the VM. While the Melusine has grown a snake or fish tail, the VM seems to have someone in a fish mouth. Even if it is female, it seems closer to Jonas and the whale.

As for the figure itself, there are quite a few examples. They have been documented as wall decorations since the 12th century (around 1100).

Originally Celtic. Melusine, goddess or protector of fountains and springs.

Examples:

https://logbuch-schweiz.net/sgrafitti-im-engadin/

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/715720565760142711/

https://josin-sgraffito.ch/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Kunsthandwerk_Sgraffito_Symbole_und_Bedeutung.pdf

https://www.google.ch/imgres?imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fpictures.abebooks.com%2Finventory%2F31171866055.jpg&tbnid=-3f_zEtuY-ktPM&vet=10CGUQMyiUAWoXChMIuKbv3LjuhQMVAAAAAB0AAAAAEBU..i&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.abebooks.com%2FSgraffito-Engadin-Bergell-K%25C3%25B6nz-Iachen-Ulrich%2F31171866055%2Fbd&docid=Ld_Bm1x7uakIlM&w=540&h=640&itg=1&q=Engadiner%20H%C3%A4user&hl=de&ved=0CGUQMyiUAWoXChMIuKbv3LjuhQMVAAAAAB0AAAAAEBU

https://www.google.ch/imgres?imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fimg.ricardostatic.ch%2Fimages%2Fb9c9914e-482e-4eeb-9d84-a5d58592a846%2Ft_1000x750%2Fsgraffito-engadin-bergell&tbnid=goMOXhn0odY1_M&vet=10CHEQMyiXAWoXChMIuKbv3LjuhQMVAAAAAB0AAAAAEBU..i&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ricardo.ch%2Fde%2Fa%2Fsgraffito-engadin-bergell-1147846236%2F&docid=r-pZd7AbBPBDdM&w=1000&h=750&q=Engadiner%20H%C3%A4user&hl=de&ved=0CHEQMyiXAWoXChMIuKbv3LjuhQMVAAAAAB0AAAAAEBU

In the comparison of the two ms. examples, they are only eight years apart and within C-14 dates. They are drastically different in artistic styles. And yet they share the technique of painting the faces with red lips and cheeks. It is certainly not a universal practice, even within a single ms., but it shows up in various situations. It’s not like artists would start using blue or green instead.

I’m curious what you have to say about the VMs “Mermaid” f79v illustration.

Based on the comparison of the VMs cosmos with BNF Fr. 565 and Harley 334, there is a similar mermaid type of illustration in Harley 334. Perhaps Harley could ‘explain’ something about the VMs, but Harley doesn’t have much to say. The mermaid is just a mermaid; not Minnie the Mermaid; not any specific mermaid; just a generic mermaid. That generic identity for mermaids is reinforced in the two Lauber illustrations in the “Book of Nature,” where a mermaid is found among the fish *and* among the sea monsters.

So, the question is whether the VMs mermaid is also a *generic* mermaid? And the answer is, No. Mermaids do not have thighs. Mermaids are fish-like from the waist down, and that is clearly not what the VMs artist has drawn, specifically regarding the central figure, although the rest of the illustration retains certain similarities. Who else might it be, if not a mermaid?

Melusine is interesting for several reasons. There are a number of historical connections, particularly to Jean, Duke of Berry (d. 1416). In addition, there are two different versions of Melusine, relevant to this situation. The more prominent version of the story is the Melusine of Lusignan, who is dragon-like, has wings, and in the end, she flies off. The alternative version is Melusine of Luxembourg. She is described as more like a mermaid, ichthyologically blue with silver beads of water, and she doesn’t fly away, but seeps into the Earth, instead.

Jean de Berry, who owned the BNF Fr. 565 cosmic illustration, also captured the Lusignan castle. He commissioned Jean d’Arras to write the book on the Lusignan Mélusine, and he is depicted in “Tres Riches Heures” along with Lusignan castle and a teeny, tiny, flying dragon. In addition to which, his mother was Bonne of Luxembourg. This purported ancestral connection to the Melusine of Luxembourg was common to all of the Valois lines. Melusine is specifically mentioned again in regard to the third generation of the Dukes of Burgundy, in a description of the Feast of the Pheasant. Melusine clearly had some significance, and it is significance at the highest level of social status. So, it would have been widely known, and therefore it’s not the knowledge per se.

What the VMs artist has done is to create a unique paired image. Melusine has been substituted for the generic mermaid of the other interpretations. It is an example of the same artistic trickery that created the VMs cosmos from two disparate parts. It is the novel pairing of “unknowns” that thwarts VMs investigation. Half the answer doesn’t work. It’s like the VMs costmary illustration, both parts are required to work together to produce the intended interpretation.

To explain it simply.

Images like these are not new.

Take the ceiling of St Martin Zillis, for example. 12th century.

https://www.alamy.com/zillis-dorfkirche-st-martin-romanische-holzdecke-mit-biblischen-darstellungen-image259835470.html

But now I go from there, 10 km south I am in Italy and a little further west in Bellinzona.

I have the battlements here, the Romansh of F116, the Habsburg crowns still apply here and it’s German-speaking.

It’s not just a book. It’s a whole cultural area. It stretches from Ticino to Slovenia.

Peter M., and ootb,

Peter, You are right – the antecedents of the west’s Melusine can be traced. Initially an effort to cope with images of Sheila na gig found in churches of the Irish and older Cetic south, those are in turn related to forms found in Roman north Africa, and the Roman east – those eastern forms also surviving in monumental works, coins and occasional manuscripts (a quite authentic late Roman example adorns the page for coral in the Codex Anicia Juliana.)

It’s not simple diffusion, but when one group of people comes up against another, it ‘reads’ the other in terms of its own customs – just as the Greeks and Romans presumed other nations’ deities were their own by other names.

Coins and monuments remain visible, or continue to be re-discovered, and that was as true, or truer, for earlier times and peoples as for our own; political change doesn’t immediately eradicate everything that went before.

Since you ask, o.o.t.b., I treated that detail quite some time ago, but a brief recap here.

The detail so often mis-read as if it were a western tradition’s ‘mermaid’ here takes a form comparable to pre-Islamic Egyptian (‘Coptic’) tapestries and images of Noah. (So far, I see, Peter has come, too)

Overall, though, I consider it to express the result of intermingling traditions from Coptos and from India, of the type we know occurred before the 3rdC AD.

(At the moment, I’m focusing on the time of Domitian).

In the research-summaries published through voynichimagery, I identified the Indian counterpart ( i.e. as master of the great Flood), and explained that in Indian tradition it is described as a form for Vishnu. I noted it was a focus of worship in only a few centres in India, and that these had been, in earlier times, ports open to foreign merchants. I also noted the Indian character in one of Kircher’s books, where his illustration is clearly one copied with minor adaptations from that in a book published by another another Jesuit who would appear to have relied on a drawing made for popular prints in seventeenth-century India.

The Vms version isn’t identical in form or atmosphere to the seventeenth-century drawings, but it is the same character in my opinion. ( remember later seeing another Voynichero mention the same Hindu deity, but cannot now recall who it was.) I’ve also mentioned that one fifteenth-century Arab navigator speaks of Noah as patron of those who venture onto the ocean flood and who are – as Homer would have said – ‘nausinous’ men. That same fifteenth-century navigator tells us that (according to the tradition he had inherited) Noah and Enoch are the same person.

I think the Vms’ type might be closer in nature to the ‘Ruh’ of Geneisis, but that aside, the more relevant point is that its astronomical counterpart is the ‘hull’ (depicted in the Vms as a log and the point of the pole as a nail) while its chief star is that we call Canopus.

I quite understand why so many people like the idea of that detail as a reference to the Latin Melusine.

We humans are hard-wired to have our eye first seek for what we find most familiar – the friend’s face in the crowd – but as things have evolved in Voynich studies, there is an added problem caused by pressure on researchers to restrict their investigation to one small region, a single medium and a ridiculously narrow time-frame. An analogy – if a poor one – would be to demand that someone research the history of ‘The City of God’ text in a late fifteenth-century French manuscript but never speak of any other region but France, and never refer to any time-range save the second half of the fifteenth century.. because someone has a theory that the author of the ‘city of god’ can only have lived when, and where, the fifteenth-century manuscript was produced, and none but a Frenchman as author will be permitted.

At present, the general state of the study simply is as it is – theory driven. What I’m waiting to see is what will happen when the first wave of historians arrives who have studied these centuries in term of a Global Middle Ages.

History of the Melusine. Short form.

As already mentioned.

Celts: Protective goddess of springs and wells.

Etruscans later called her goddess Reitia. Documented from the 5th-1st century BC.

https://www.sagen.info/forum/media/raetiaquelle.1156/

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/R%C3%A4tia-H%C3%B6hle

Romans later also called her Juno.

The church could not ignore her, she was too powerful and well-known for that.

Used as a patron saint.

https://www.matriarchiv.ch/uploads/003-Literaturliste-Frauen-Kultur-Landschaft.pdf

Today known throughout Europe as the Queen of May.

Remember, nobody does the same job for 3000 years, but she’s still around.

Peter M.,

Your post date-stamped (i.e. approved) May 3, 2024 at 6:55 am had not appeared when I wrote mine (approved on May 3, 2024 at 7:32 am), which replies to your previous one.

Forgive me but I will not follow your ‘alamy’ link because the site lists 31 tracking cookies as ‘essential’ and says some will continue tracking us for more than a year.

To make a good ‘battlements’ argument would take a lot more than just mappin where there happen to be swallowtails today.

To make it good, one would have to eliminate all the examples which date to the nineteenth century, when a sudden swelling of post-Napoleonic nationalism, combined with a nostalgic version of the medieval period seen in histories and in art, inspired widespread “renovation” which may or may not reflect the situation when the Voynich manuscript was made, let alone at the time that detail was first added to its map.

Having checked each extant example and eliminated the anachronisms, you would also have to determine the historical range over which swallowtail merlons had adorned battlements between (say) the time of the first crusade and 1440, using sources other than European ones because although we know many castles and forts were built during those centuries, a great many have now been demolished or re-built beyond recognition, or at the very least seen the fortifications demolished by war.

Reconstructing the situation when the Voynich quires were inscribed would be work enough, but since there is no reason to believe all the manuscript’s content first created then, you’d have to start by re-creating the general distribution for such forms even earlier – say, from the time of the first crusade to the beginning of the fifteenth century (or at least the mid-fourteenth).

As if that weren’t enough, if you refer to images as evidence, it is necessary to establish by fairly solid comparative studies, the degree to which a given example is intended literally. As imaginary example, you might find such merlons represented on a coin made for medieval Crete. It might be a portrait of a lost fort or castle, or that motif might have been included (as so many were) not as literal, but for the cultural significance it bore or even simply as an attractive ornament.

While I don’t claim to have undertaken an exhaustive study of the motif in art – it would have taken longer than the three years’ I did spend working through the Voynich map, but I can say that for many more reasons than one, I concluded that ‘castle’ was a token form for Constantinople and/or Pera, and that the constant implication of the ‘swallowtail’ motif in any form, literal or figurative, that the area enclosed (whether a city or a structure) was still, at that time, a sign that the area was under imperial protection. Not necessarily of a Christian emperor, but usually. That is, It marks an ‘imperial limit’ in something of the sense we say a foreign embassy is ‘foreign territory’ no matter where it is. It is also true that the Voynich map’s example is not entirely surrounded by swallowtails, but shows half-and-half ‘swallowtail’ and ‘square’.

I know the ‘swallowtails’ argument looked very promising in the early 2000s, and I sympathise.

@Diane

You don’t need to go to Alamy, Wiki works too. Doesn’t have as many pictures, but enough to see what it’s all about. Otherwise just search for the church and look at the pictures.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Martin_(Zillis)

About the battlements. Simply put, there are none. (Mediterranean area) Everything after 1500 are trade fortresses built by the Doge of Venice. The time of castles was already over by 1400. They switched to star-shaped fortresses because of the cannons.

Written records such as ‘Nobody can live in this shithole anymore’ already existed in the 14th century, when the death of castles had already been underway for 100 years.

About the coin. I’m sure it’s three-pronged, otherwise give me a link.

Peter M.,

Please share your references, or a source for your thinking that all swallowtails post-1500 were built by the Doge of Venice. Or did you mean all castles built after 1500 were built by the Venetians? If by ‘trade fortresses’ you are thinking of Caffa (Theodosia), or of another site in that region (the one I’ve identified as the place indicated on the Voynich map as the site furthest north known to the original makers), then I think you need to re-visit the history of that region.

But then again, since we have no concern with anything post-1500, the point is moot. The manuscript’s absolute upper limit (as I’m explaining in a post now) is 1439 AD, and that’s only for manufacture, not dating the content.

Peter, Would I be right in thinking you’re a convert to the latest mutation of the ‘Germanist’ position, one that now tries to annex all the maritime and cartographic, mercantile and similar material I introduced to the study, by swapping Genoese and Jewish for a new Germanist- Venetian-and-Dalmatian-maritime-militarist-trade and medicine” sort of theory?

Peter M.,

Thanks so much for the link to the church in Zillis. What a beautiful creation that ceiling is. Some very interesting and apparently paradoxical features – notably the form given Satan – at least as we see it now. Also interesting is the amount of meat on the people’s bones. Somethin about it reminds me less of late Roman works than of drawings in one early English manuscript. I cannot link it here; the British Library’s digitised manuscripts are offline, but if you’re interested, the text is popularly known as the Poems of Caedmon and I’ve always had a vague suspicion that it reflects a tradition gained from pre-Islamic north Africa rather than from the Carolingian court. Never found time to really explore the question, though.

Thanks again.

Not all buildings have something to do with Venice. Italian architects and architecture were simply in demand. People wanted change. The changes in Moscow alone are remarkable.

On German studies. Apart from the few German words and the crowns, I don’t see anything that really points to German.

I just try to categorise what I see or don’t see.

Example: I see church spires with high peaks and buildings with steep roofs. This suggests a high snow load.

But what I don’t see are domed roofs or flat roofs as would be normal in the eastern world. Arabic and Greek architecture.

I don’t see any reference to the east, but everything in the west. Even the city gate resembles a known city gate almost 1 to 1. Barrier walls as seen in the VM near the castle are only built in mountainous or very hilly terrain. Otherwise they are useless. Or oriel towers on buildings and walls are western architecture.

I can’t ignore that.

Back to the hats.

Both can be seen in this fresco. The cap of the Pfaff and the Jewish hat.

Remarkably, if you look at the other pictures you come to the entrance gate. At the top right it looks as if 2 women are being crucified.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reformierte_Kirche_Waltensburg#/media/Datei:Waltensburg_Kreuzigung.jpg

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reformierte_Kirche_Waltensburg#

@Peter M.

It is not a clerical cap. The clerical caps of today are derived from that model, but at the time it was just a cap for people of higher status.

The pdf I linked on April 25th explains it all with a lot of references to historical depictions. It is a cap called biretta or birettum in medieval latin, that evolved to the modern priest cap and doctoral cap after the 15th century.

—

Regarding merlons: there are enough sure traces of swallowtail merlons from that era. Merlons are weak structures, so they are easily destroyed and rebuilt. However it happens that they are incorporated in some new structure when the castle is renovated, and so they are preserved until these days, as they were, and they can be surely dated:

https://d13gisi6iet4nc.cloudfront.net/odm-prev/p,fc,2018,meldola,rocca_di_meldola,c,30317,diego_baglieri.jpg

http://www.icastelli.org/tecnici/complementi_difensivi/merli/Sabbionara_03.jpg

Peter,

I’m not sure what you mean by ‘oriel towers’ but (I’ll quote a website so you can check this)

Origin of the Oriel:

This type of bay window probably originated during the Middle Ages, in both Europe and the Middle East. The oriel window may have developed from a form of porch—oriolum is the Medieval Latin word for porch or gallery.

https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-an-oriel-window-177517

I don’t know where, in the Vms, you see an oriel window so just as a general remark, medieval Cairo was filled with ‘oriels’ and you still see them in 19thC and early 20thC engravings.

Also, regions of heavy snowfall extend around the world, and people’s response is much the same everywhere it does – a steep-sloping roof.

As for ‘church spires’ – I won’t try to change your mind, because I’m sure that you’re sure it’s what you’re seeing. I will say that unlike Mr. Blackhirst and others, I do not consider any image in the Vms indended to represent a form of Christian church spire.

@Guido

That’s a brilliant image for how structures can evolve over time.

My point to Peter was that before pronouncing on the intention of detail like the map’s “castle”, it is necessary first to treat it as small detail in a six-hundred year old drawing. Why suppose the image meant literally? Why presume that, if it were ‘landscape drawing’, the building can only have been in Europe? Why suppose, even so, it must have survived? You might find it interesting to research the statistics for that.

@Diane

You think of this fortress when you think of Caffa?

I can’t find any of these battlements. There’s nothing in the paintings of the conquest either. Why don’t you give me a link so I can see if we are talking about the same castle.

https://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:THEODOSIA_01.jpg

@Stefano

Thanks for the tip on the battlements.

We all know them where temporally in question.

See:

https://www.voynich.ninja/thread-3643.html

https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?ll=45.17933758614477%2C13.139149429745203&z=6&mid=1y1hxOfGDFhqo97deJVvFNi7ASspTlp9v

It’s a simple priest’s cap. From about 1350.

PS: by Voynich-Ninja I am Aga.

Sorry

Pfaff = Priester, Pfarrer,

Variant from the Alemannic. (southern German region)

@Diane

Bay windows like the one you show are indeed everywhere. Even in India. But this is more of an enclosed balcony.

What I mean is a defence tower to watch the wall without having to lean out too far (side protection). But it can’t be reached from the ground either. To be seen 2x in the VM.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scharwachtturm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartizan

There is certainly snow everywhere. But again, you’re only looking at one piece of the puzzle. But it must also fit in with the other parts. You write ‘medieval Cairo’ OK, and how much snow a year? And they have flat roofs.

On the subject of the church tower. What else is it supposed to be? A rocket launcher? Mothership + tower is a church.

Round dome and tower is a mosque, but I don’t see it. OK, sometimes a nuclear power station.

As the artist shows in this fresco. The forecourt to the gate to protect the entrance. The VM_artist draws exactly the same thing on his textbook city gate.

Example:

Trento, Torre dell’Aquila Ciclo dei mesi ca.1397

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ciclo_dei_mesi#/media/File:Ciclo_dei_mesi,_gennaio.jpg

Peter,

I don’t think Caffa is the subject of the “castle” in the Voynich map; it’s just one example of ‘swallowtails’ which survive on structures from other places around the Mediterranean. I’ll link to an image I used in a research-summary treating the ‘castle’ and the map’s North emblem.

https://voynichrevisionist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/archit-details-swallowtail-caffa.-remnant-of-medieval.png

If you want to see a few more examples of remnants not in western Europe, just skip down to the second part of this post – at voynichrevisionist.com

D.N. O’Donovan, ‘Reprint – Towers and swallowtails. North emblem and north roundel’, voynichrevisionist, ( February 26, 2023)

‘https //voynichrevisionist com/2023/02/26/reprint-towers-and-swallowtails-north-emblem-and-north-roundel/

When I described the sort of work needed for this research, I wasn’t theorising. 🙂

1. it is not Caffa but Sudak. Caffa has no such battlements.

2. probably renovated after 1958. work is still in progress.

We are currently working on it on Ninja.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genoese_fortress,_Sudak

I think the castle is just fantasy, but with details on the rosette side where the draughtsman saw it. I know some castles that are similar.

Don’t let yourself be fooled. An example: original battlements and replica from 1960.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%96k%C3%BCz_Mehmet_Pa%C5%9Fa_Kervansaray%C4%B1

I think you should take a closer look at your work.

Peter – thanks for the link to Sudak.

It was, indeed, another of the Genoese enclaves on the Black Sea, but your image of it shows no ‘swallowtails’ there, while the image to which I directed you – and which does – was certainly an image of remnant of Caffa photographed in 2011, though given recent events, they may not still exist.

Caffa was, as I suppose you know, the enclave from which plague-bearing ships are generally said to have fled, to infect ports of mainland Europe.

You might be interested to know, too, that I suggested in that same post of 2012 that the red ’emblem’ on folio 1r is token for [Tartaria] *Aquilonarius* ‘, the name given to the Franciscan Vicariate of which Caffa (not Sudak) was the centre – this according to a Franciscan inventory taken in 1350.

I’m sorry to say that I had kept the photograph, and its documentation, in hardcopy and, with much else, that file was lost to a bushfire in 2013, so the only evidence I have now is the photo as I published it at voynichimagery the year before.

If, at last other Voynicheros are starting to follow up on the work I did back then, and looking at the Black Sea in connection with cartes marine, Genoa, and the east-west trade during the fourteenth century, may I recommend again the ground-breaking study which was so helpful to me as that work progressed through to 2011-13.

Virgil Ciocîltan, The Mongols and the Black Sea Trade in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, [series] East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450-1450, Volume: 20 (2012).

Peter, don’t hesitate to comment if you think I’ve erred. I can’t tell you how often over the years I’ve found that something another person says seems to make ‘no sense’ not because I know more, but because I know less than they do. Mark Twain once remarked that, at the age of 18, he wondered how his parents could have lived so long and learned so little, but by the age of 22 he was pleased to see they had learned so much in just five years. [smiley emoticon]

To conclude.

1. caffa has no dovetail battlements. The tower is in Sudak. The picture of the tower with the battlements is the last tower on the left below the mountain top.

You can see it in the panoramic picture from Wiki.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genoese_fortress,_Sudak#/media/File:%D0%93%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%83%D0%B5%D0%B7%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%B0_%D1%84%D0%BE%D1%80%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%86%D1%8F._%D0%9F%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BC%D0%B0.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genoese_fortress,_Sudak

This is exactly the tower you show on your website. Photographed from top to bottom.

https://voynichrevisionist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/archit-details-swallowtail-caffa.-remnant-of-medieval.png

The tower can also be seen in another picture. Photographed from bottom to top.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/20/%D0%94%D0%BE%D0%B7%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B0_%D0%B1%D0%B0%D1%88%D1%82%D0%B0_%28%D0%9A%D0%B8%D0%B7-%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BB%D0%B5%29%21.JPG

The same tower (around 1959) also photographed from bottom to top. As you can see with 2 original battlements, one on the wall and one on the tower.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/79/Sudak_Fortress_Girl_tower.jpg

You can also see what the wall once looked like in a 3D reconstruction. (Spanish company).

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/06/Parque_arqueologico_reconstruccion_2.png

No dovetail battlements before 1500. here only around 1960. again. in the first half of the 20th century it seems to have been a fashion trend.

What happened? ( summarised from various reports).

No dovetail battlements before 1500. here only around 1960. again. It seems to have been a fashion trend in the first half of the 20th century.

What happened. (summarised from various reports)

Due to the increasing number of tourists (beach and sanatorium), Moscow (CCCP) has started construction work without taking historical accuracy into account. Figurehead and fashion trend.

Shortly afterwards, the work was cancelled and responsibility was handed over to Crimea/Ukraine. This work is still being carried out today in a historically correct manner.

So the tower is to be seen as propaganda and not as a historical feature.

Addendum to the severe damage to the walls.

Russian-Turkish war in the 18th century.

Russian-English war in the 19th century.

WW1 and WW2.

But the main culprits were the locals who used the walls as a quarry to build new houses.

Therefore it is more of a reconstruction than a renovation.

On the World Heritage List.

Peter M.,

I understand why you think the photograph I showed you was from Sudak, and I can see that there’s no point in trying to change your mind, even by saying I’ve been there – so I shan’t try.

You are certainly right that there was a wave of nostaglic ‘reconstruction’ during the nineteenth century. We agree on that – and I made the same point about superficial ‘mapping’ examples from western Europe, including Italy or the Val d’Aosta.

And as I said at the outset, I wasn’t claiming the Voynich detail a reference to Caffa. My conclusion was that it is a token for Constantinople-Pera. If you saw the post I cited, you will see an example of a Latin image which employs the same ‘swallowtail’ motif as a symbolic token only. As far as I could discover, if any of the walls of Constantinople really had swallowtails, no-one has found a trace of them, and the opinion of the archaeologists I consulted was that if there had ever been ‘swallowtail’ battlements there, they would have probably been on the walls which the Genoese built ‘illegally’ – that is, in despite of the rules imposed by the Byzantines on foreigners permitted enclaves on either side of the golden horn.

Sudak certainly was another important Black Sea site, though more so after 1350 than before. I realise, too, that you feel perfectly convinced that the image I showed you was of Sudak, not Caffa, and that you are unlikely to change your idea, but it is only fair to others to repeat that you are mistaken on that point, and that the photo was *not* taken at Sudak, but in Caffa.

Whatever your ideas about that, the basic point remains that you have to deal with the questions of whether that detail on the Voynich map is (a) meant literally and (b) represents a structure still existing with such battlements today as were there in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, and (c) could not be meant for any structure since erased.

Exactly the same set of problems would have t be dealt with if you thought the Voynich map contained the image of, say, a lighthouse.

@Diane

I think you are wrong. It is Soduk.

Otherwise you have to explain to me why the centre pinnacle is broken off in both pictures and why the photo you used is on the tourist side.

https://hotels24.ua/news/%D0%A1%D1%83%D0%B4%D0%B0%D0%BA%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%8F-%D0%BA%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%82%D1%8C-10230995.html

The symbol you show as a figure is a chess piece and is called ‘Roch’ and it is the tower. We also had it here.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roch_%28Heraldik%29

So, and now another topic.

@Diane

To be fair. Here you have a panoramic all-round view of the fortress and harbour of Caffa.

No hills, the terrain is quite different. No renovations. 2 or 3 towers, some wall, the harbour. Looks similar, that’s about it.

https://www.google.com/maps/@45.021519,35.3996484,3a,75y,324.77h,87.66t/data=!3m8!1e1!3m6!1sAF1QipMyT0C92sx8XdGEgX08vdjUX9T1w2Xqzm9RL63R!2e10!3e11!6shttps:%2F%2Flh5.googleusercontent.com%2Fp%2FAF1QipMyT0C92sx8XdGEgX08vdjUX9T1w2Xqzm9RL63R%3Dw203-h100-k-no-pi-2.1388366-ya259.0863-ro0-fo100!7i8704!8i4352?entry=ttu

https://www.google.com/maps/@45.022188,35.4020481,3a,75y/data=!3m8!1e2!3m6!1sAF1QipOjPzwfI-nYKxVmbuGlNV99gm6RUEi_nuHTleLt!2e10!3e12!6shttps:%2F%2Flh5.googleusercontent.com%2Fp%2FAF1QipOjPzwfI-nYKxVmbuGlNV99gm6RUEi_nuHTleLt%3Dw203-h146-k-no!7i1500!8i1082?entry=ttu

According to a painting from 1783, Caffa must have been huge. Unfortunately, nothing can be seen today.

Wiki:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feodosia

Peter,

Yes. Caffa was the chief Latin enclave in the Black Sea from the 1290s until the 1350s. It was a Genoese grant but a mixture of people lived there.

Venetians really had to struggle in the earlier part of that period to gain any presence in the Black Sea – through which now, much of the silk and spice routes’ traffic was re-directed after loss of Latin holdings in the Levant, and due to ongoing disruptions caused by war. During this period and through that same troubled ‘fertile crescent’ region, is also when we see emerge texts instructing professional scribes how to encipher and disguise the intention of writings. For example, one method involves separating out the elements of a cursive script.

But let me get your position clear about those ‘swallowtails’. Is it your contention that such merlons were only ever made within Latin Europe, and that their presence in a detail on the Voynich map must be (a) literal and (b) prove the structure one which existed in Latin Europe and (c) that it must be one still standing there today?

One has to admire the amount of work which went into Koen’s project to map points where he, or a member of Voynich ninja, found a photo or building with swallowtails on it today. (That’s the Google-tool map you linked to above).

There was no historical research required, though, and the majority of contributors hold a Eurocentric-Voynich theory, so the map doesn’t differentiate between authentic and later, romantic, use of those merlons, and only Koen considered the question of Latins’ fortified structures outside mainland Europe, so – as I’m sure Koen would be the first person to say – that map is certainly interesting, but should not be mistaken for any final word.

Peter, the really interesting thing about Caffa and other sites granted to the Genoese around the Black Sea is their antiquity. Some were already two thousand years old. But in was in Serai that a Venetian traders’ guide says the trader should hire a Dragoman able to speak Cuman.

If the central bit isn’t meant for the round pom-pom but a more pointy form – three of your examples suggest that, but who can be sure when the draughtsman was working to such a scale? – it might have been originally a form of petasos.

There’s a statuette from Tanagra in Boetia wearing it – that object’s in the British Museum. Other examples include a very nice one in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin. Those and others are also pinned by Kat Max to his/her pinterest page.

https://www.pinterest es/pin/387731849161369901/

I don’t rule out, either, it’s being a form of that ‘beret’ we see given by Romans to an older and Phoenician ‘Asclepius’ – known as Eshmun.

I’ve been a bit reluctant to mention Eshmun because I’ve a post in the pipeline which mentions him in relation to Asclepius and that post won’t go up for at least a month. Still, fair do’s…

The best ‘hatted’ examples of Eshmun are on Roman-era coins.

One is from Leptis Magna, Libya – east from Tripoli. (the linked caption as ‘Lepcis Magna’). That image suggests the pointy bits supposed to evoke his swift help (i.e. his former wings)

https://br.pinterest com/pin/24136547980389517/

Assuming the Voynich draughtsman’s hand as steady as a jeweller’s, I think that comes closest.

There is another interesting hat, on a coin dated 1stC BC, which nicely bridges use of the type in Babylonian or Assyrian with the later Turkish ‘fez’. In numisma-speak that sort of hat is a ‘low kalanthos’.

https://www wildwinds com/coins/greece/phoenicia/berytos/SNGCop_87.jpg

If the links won’t work, readers might have to go to the wildwinds site and sign in (no cost, no obligation, no subscription – just anti-nuisance precaution).

Nice image of the men’s petasos [has top-knob]

https://hatguide.co uk/petasos/

The petasos, and the zuccato were worn by ‘Byzantines’ according to one source cited by the wiki article. That source is at archive.org but gives little detail, just

“Several hats inherited from the Greeks were worn, including the Phrygian cap and the petasos”. No specifics for the medieval centuries.

In the archive.org edition I’ve looked at (one-hour borrow), it is on page 267.

Reference given by the wiki article differs a little –

Sara Pendergast and Tom Hermsen (eds.), “Headwear of the Byzantine Empire.” in *Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear Through the Ages*, 2nd ed., vol. 2: Early Cultures Across the Globe, UXL, 2013, pp. 257-259.

Nick, I think I can say with a fair degree of confidence that the original draughtsman (who lived date and place unknown) intended the hat with ‘knob’ for the mens’ petasos, and perhaps not the version made of straw, but the military helmet, messengers and warriors (angeloi and – perhaps – male ‘hosts of heaven’?).

This won’t suit many Voynicheros, but is entirely consistent with much else I’ve found while working through the manuscript’s drawings.

This doesn’t, alone, determine when or where the drawings were first enunciated

because Greek remained a popular lingua franca through much of the lower and eastern Mediterranean sphere into the Roman- and much of the medieval era, even after the advent of Islam. Not that I’m suggesting Voynichese is or isn’t Greek; only that it would be wrong to suppose older Greek images would make no sense once the Roman empire came on the scene.

(Nick’s question has pushed me, finally, to order replacements for a couple of history-of-clothing books lost some time ago. )

About another type of headwear seen on figures in the calendar – the type about which Nick asks, ‘What kind is this, then’,

https://ciphermysteries.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2024/04/image-3.png

I’d suggest the Greeks’ *kausia*, whose modern descendant is known as the ‘pakol’

Side-by-side image of the Ancient and contemporary forms at

https://greekreporter.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/kausia-and-pakol-credit-British-Museum-public-domain-wikimedia-commons-Mostafameraji-CC0-wikimedia-1392×1035.jpg

That image from an article online:

* Alexander Gale, ‘Ancient Greek Hats: Headwear in Antiquity’, Greek Reporter,

(November 7, 2023).

I’d allow that the more heavily-overpainted figures’ hats might be intended to resemble the ‘chaparon’, one cannot presume that had been the intention of the original drawings. Looking into the image of the calendar’s archer, or rather into its lineage, I found forms of tailed hat which were certainly not chaperons and which appear, even in western Europe, among peoples as far distant as Dalmatia and Spain, and by not later than the 8thC AD.

Also, true turbans were being worn by some Latins in western Europe during the fifteenth century – so while the usual theory is that the true ‘chaperon’ adapted the European peasant’s hood, it’s not necessarily the case that the Voynich drawings were meant for those.

In 1500, when Vasari painted scenes from the life of Cosimo de’ Medici, we see that he is still tries to convey a person’s intellectual lineage by the type of headwear they are given – Cosimo wears a form of ‘kausia’ while Paolo de Pozzo Toscanelli wears an authentic style of tribal ( Mahribi?) turban.. and so on.

See

https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/paolo-dal-pozzo-toscanelli/

If the treccani hotlink doesn’t work for you, try

https://www.lindahall.org/about/news/scientist-of-the-day/paolo-toscanelli/

or just search

Vasari Cosimo Toscanelli

– the Toscanelli detail is often reproduced.

For “in 1500” read “in the 1500s” – that work was begun late in the sixteenth century, some say c.1550, others have it begun in 1575 or so.

D.N. O’Donovan

Could be on a winner with your Greek headware; Considering that painters Ted and Maggie Taylor nee Boole along with their art ‘student’s were regular visitors to traditional living rural localities in Hellas as well as Italia at turn of the last century. All seems to fit nicely, along with other significant findings for VM proof of Boole family authorage, wouldn”t you agree?

John Sanders,

No, I don’t agree with theories that the Voynich manuscript’s drawings should be attributed to any persons who lived later than c.1438, and in my opinion although some few may be reasonably argued fifteenth-century additions, the majority were gained from “considerably older” sources (pl.) The figures in the calendars’ tiers reflect a habit of drawing both older than, and different from, the central emblems’ and while the addition of heavy pigment is obviously the last phase of the drawings’ evolution, and may be attributed to the fifteenth century, the central emblems are in an earlier style, and the tiered figures one that suggests derivation from a Hellenistic original .. in my opinion.

John, re

“the Voynich manuscript’s drawings should be attributed to any persons who lived later than c.1438,” I should have said born later than…

One exception I should mention is the drawing on folio 57v., which might possibly have been a seventeenth-century addition, though apparently drawn on a blank leaf in the manuscript. The iconographic evidence (plus Rich Santacoloma’s observations about its three centre-points) is what leads me to suggest it a very late addition – by reference to a drawing in one Kircher’s books, and what is known about the sources he used. Against this evidence, though, is McCrone’s saying they found no obvious difference in the inks used throughout for writing and drawing.

Diane: but what about the white porcelain ware, the cast iron pipes & fittings, the plumbed & lined free standing pools, Victorian lady typist, the wing shot albatross, Bouvelocque’s pelvimeter with measure stick &c..To my reckoning they point to some time even beyond your seventernth century add on contentions. PS. I could be mistaken about the vintage Coca Cola bottle on f1r near the worm holes top right.

… It would seem that people who were neither Europeans nor Mediterranean Greeks wore petasos-style hats. I’ve just come across the image of two Islamic astronomers wearing them – the source is undocumented, but I’d *guess* the image is of a Mongol-era Islamic observatory, in which case, late 13thC or 14thC.

See at 6:09 in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r-T5yxZWXzs

John, concerning

“…white porcelain ware, the cast iron pipes & fittings, the plumbed & lined free standing pools, Victorian lady typist, the wing shot albatross, Bouvelocque’s pelvimeter with measure stick &c..”

As I’ve said recently, when people expect to see only what is already part of their mental landscape, that’s what their memory will throw up as next-nearest thing. “What you get is what you’ll see.”

Believe it or not, it takes conscious training, and some mental discipline to remain as keenly aware of what, in a drawing or on the page, is unfamiliar. Imagination will constantly try to invent a story about it, to make its *un*familiarity less discomforting.

One technique is to accept a first, subjective impression for what it is, and then ask – seriously – ‘what else could it be?’. And when you’ve done some research and have a number of possibilities – such as, what if the ‘white porcelain’ is white-washed brick, or white stone, or just a drawing the painter was not inclined to spend time painting… etc., you might try to decide which (if any) better suits all the information from codicology, palaeography and materials science.

Have you looked at the way people represented their dividers (compass) during, say the 10th-15thC? How about in non-Latin works? Byzantine works? What if the instrument is a measuring tool and not a medical instrument at all, let alone one made so late as your imagination’s ‘match’ suggests?

Iconographic analysis isn’t like a game of happy families. You don’t always hold enough already in your hand to win.

Diane: agreed, one medical instrument of the correct size shape and appendage, doesn’t make a set of pelvic obstetric calipers; but when one takes time to input the surrounds and the narrow hipped pregnant nymph and the instrument toting

attendant for etc., the chances of said pelvimiter being anything but, be product of uncompromising blind ignorance and arrogance, so typical amongst medieval VM stalwarts like your good self madam.

John ‘ .. “like your good self Madam?” really!!? Perhaps you’ve been binge- watching Downtown Abbey or Wodehouse?

Back to the topic of hats found on VMs White Aries. An interesting explanation can be made based on the often-overlooked medieval science of heraldry. The investigation of heraldry reveals historical connections to the origins of religious tradition as well as the artist’s subtle methods of deception and confirmation.

The key to this heraldic interpretation is the VMs nymph in the inner circle of White Aries at about 10 o’clock – the one with a reddish hat, standing in a tub with blue stripes. Given the ecclesiastical and armorial heraldic interpretations represented, this constitutes a potential historical connection. In effect, the image presents the puzzle of the Genoese Gambit. Does the investigator know the armorial insignia of the pope who initiated the tradition of the cardinal’s red galero?

Intentional duality and other factors attempt to disguise the historical interpretation. Structural and positional factors based on religious and heraldic tradition are used to provide four independent, objective confirmations of the historical interpretation.

Mdm. Diane: Suggest you make a closer study of two nymphs, one with the non child bearing hips, t”other with mit calipers and take particular note of the setting. Then google up ‘Pelvimiter images’ which will be an eye opener I’m sure. You’ll see that they all bear the same general characteristics and compare favourably with those in f80r, including the Jean Louis Baudelocque 1789 pat. measure’ stick. When you’re satisfied that my hand is in fact a winner, then we can continue with other objets d’art to be found in VM that display more latter day date determining clues.

Sorry for the miss address ie., ‘madam’ in my previous post which was not meant as an insult.

@John Sanders

When you use the word ‘pelvimiter’ you create the impression that the people who did the C-14 carbon test are morons.

Just try using a different word. ‘Example gripping circle’ has been around for 2000 years and looks the same.

https://www.google.ch/imgres?imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fnew.e-flip.at%2FIngLehrer%2F201944%2FLehrer_Hauptkatalog_2021_22%2FpubData%2Fsource%2Fimages%2Fpages%2Fpage302.jpg&tbnid=kAT6McZcAiuvQM&vet=12ahUKEwi9xJiinq2GAxU7jv0HHfBBC7IQMyg1egUIARD7Aw..i&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fnew.e-flip.at%2FIngLehrer%2F201944%2FLehrer_Hauptkatalog_2021_22%2Fpage_302.html&docid=tfFlHxRaMlj37M&w=598&h=845&itg=1&q=Greifzirkel&ved=2ahUKEwi9xJiinq2GAxU7jv0HHfBBC7IQMyg1egUIARD7Aw

Exemples

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greifzirkel

On this way.

https://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=258834

Not you again moron baiter. Last time, I recall you sent a link depicting a three three ton forest tree puller. Get real or back to your Swiss style alchemy.

@Sanders

You are right. I’d better stay in Switzerland. Why should I argue with someone like you who has the IQ of a housefly.

Peter M: be careful, or I’ll start getting cross comments from houseflies.

@Nick

Yes, you are right. Why do I even react to something like that.

Nick: got to admit your TIC veiled threat re dumb horseflies deserves an imogi or, failing that, snide snickers from dedicated’zodiac nymps & aries hats’ commenters, all four of them by last count!

Peter M.,

I think ‘Calipers’ is the English for Greifzirkel?

I recall seeing a man haul blocks of ice using something similar, and I’ve already tried (and failed) to balance the ‘pelvimeter’ notion by citing this example of geometrical divider/compass. (By the way, she’s not a ‘woman teaching geometry’; she’s personified Geometria.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Woman_teaching_geometry.jpg

I wonder if there’s a museum somewhere that has a collection of ancient and medieval measuring instruments?

Not that it has anything to do with Nick’s post, but Alamy has an interesting image of what it calls ‘Roman to medieval’ dividers and calipers. Reconstructions, but in fact reconstructors have to work for pub-quiz-level nit-picking amateurs who know a lot about the minutiae, so they do the research. The calipers look fairly right, I think.

https://www.alamy.com/roman-to-medieval-dividers-and-calipers-reconstruction-by-daegrad-tools-image245320494.html

Yes, the reconstruction (Alamy) image seems to be pretty right.

Here is a definitely Roman version from

“Marble relief of a woodworkers shop, originally from an altar perhaps dedicated to Minerva. Tools from left to right are a frame saw, a carpenters square, a calliper, a bucksaw. … L. 1.38 m, H 58 cm. Capitoline Museum (Montemartini) Rome. late first century. [photographic-] Image see R.B. Ulrich, Roman Woodworking, (2007) Yale Uni Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10341-0. Also at archive.org.

Image reproduced in the St.Thomas Guild blogpost (blogger) 19 January 2013.

https://thomasguild.blogspot.com/2013/01/the-medieval-toolchest-compass-calliper.html

Would you believe it! Those male nymphs are getting around!

https://www.morgansrarebooks.com/products/house-flies-and-how-they-spread-disease-by-c-g-hewitt

Rich Santacoloma (re hash of 2018 comment)

Jean-Louis Baudelocque 1745-1810 was a French obstetrition who studied and practiced Medicine in Paris. He was known for making midwifery obstetrics a scientific medical dicipline. He is credited with refining Andre Levret’s 18th century “pelvic forceps” and constructing a pelvimiter for use in determining the viability of pre delivery normal child birthing potential. His anthropometric calipers were used to measure external pelvic dimensions (see f80r), the measurement obtained thus becoming known as “Baudelocque’s diameter” (external conjugate diameter of the pelvis). The “compas la mesure pelvimetrie extern…..” with stick micrometre was patented in 1889 and, in 1806, Napolean appointed Baudelocque (IQ of a housefly according to some) as first chair of obstetrics in France…..

@Diane

What you are looking for are ‘gripping pliers’. I don’t know exactly for the English one. They come in different sizes.

For example. Small tongs are for holding test tubes over fire, but also just as tongs for sugar cubes.

Large ones, for example for 2 people to carry blocks of ice or in a horse harness to pull tree trunks out of the forest. But the principle is always the same.

Examples:

https://www.google.ch/imgres?imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fi.etsystatic.com%2F11559025%2Fr%2Fil%2F40cbb5%2F1933070592%2Fil_fullxfull.1933070592_maer.jpg&tbnid=_WJwY0MDiWdGZM&vet=10CBkQxiAoCmoXChMIuI6-qoawhgMVAAAAAB0AAAAAEAw..i&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.etsy.com%2Fde%2Fmarket%2Feis_block_zange&docid=-1s5v9FyShlYjM&w=1711&h=1711&q=Greifzange%20Eisblock&ved=0CBkQxiAoCmoXChMIuI6-qoawhgMVAAAAAB0AAAAAEAw

https://www.ebay.at/itm/194176559441

@Diane

What you were looking for ‘ice block tongs’.

You can find them in the atiquities market.

Formerly also used on the railway as rail supports.

https://www.etsy.com/ch/listing/1514123023/antike-eisblock-zange?click_key=a38c09b46abd333275d0f693b5dfd20218911455%3A1514123023&click_sum=22a69979&ref=sold_out-1&pro=1

@Peter M.

Perhaps you would consider puting your jumbo forest tree pulling tongs up again for misguided medieval Voynicheros who missed it first tine around to swoon over.

….patent date for Boudelocque’s clever device which was continually improved upon (google Pelvimetrics) up until the present (even digital variations), was in fact 1789 not 1889 as earlier misreported.

Folio 80v. When the scientist will be able to read the text. That’s how he finds out that there are painted corners in the picture. corners. The reason why the horns are painted on the picture is that Eliška’s father is also described as = goat in the text of the manuscript. He liked making love and sex and intercourse. That’s why Eliška calls him = goat. Next to the picture is written when Eliška’s father was born. (birth of a goat). ( goat = text = cocco , 37337 ). Below that is a picture where a woman is painted holding tears in her hand. ( 3 tears ) As is of course also written in the text next to the picture. So it says when Eliška’s father died. (that’s why the 3 tears are drawn there). John II from Rožmberk, he was born third in line in the family. Third birth. And so Eliška also writes about him as the third. There are also year numbers in the text. 1431 = birth of John II. from Rožmberk. In 1472 John II died. from Rožmberk. He died of the plague.

There are no pliers in the picture. Neither pelvic, nor on ice, nor on rails.