After all the factuality of Part 1 and the opinionicity of Part 2, it’s time to actually start attacking Quire 20’s block. The issue of how exactly to attack remains tricky, but let’s give it a go and see how far we get.

Ditto?

In part 2, I argued for the presence of some quite specific parallels between Q20’s recipe-like blocks and the recipes in Lat 6741. One particularly interesting comparison was between Philip Neal’s “horizontal Neal keys” (pairs of single leg gallows, typically found 2/3rds of the way along the top line of paragraphs) and the second coloured initial in Lat 6741 that typically separates a recipe’s title (e.g. “ad faciendum…” etc) from the main body text of that same recipe.

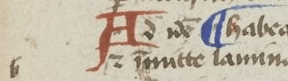

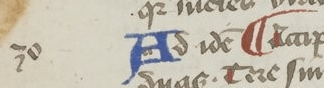

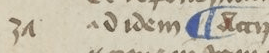

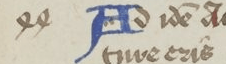

However, not all recipe titles are the same kind of length. Notably, there are some short ones that use “Ad idem” to mean “ditto“, i.e. ‘use the same title as the preceding recipe‘. You can see these in the following Lat 6741 recipes:

#6…

#30…

#37…

#44…

#62…

#80…

#84…

#88…

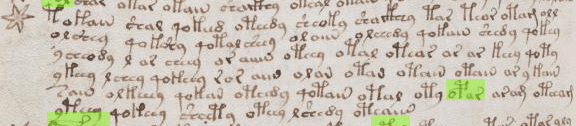

Can we see any hints of this “ditto”-like behaviour in the top line of the Voynich Manuscript’s Quire 20? We can certainly see many Q20 paragraphs that resemble this kind of thing:

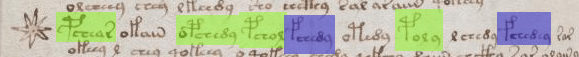

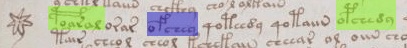

f103v:

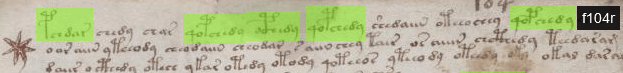

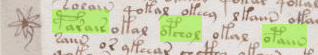

f104r:

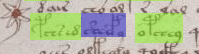

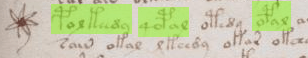

f105r:

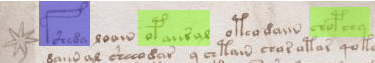

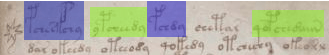

f106v:

f107r (note the pair-heavy EVA “aralorar” in the first word of the line):

f107v:

f112r:

f113r:

On balance, though, the honest answer is… not really. In fact, even though there are plenty of lines that kind of resemble the ad idem recipe pattern, the sheer variety of word types in, between, and around these single-leg gallows is really quite… impressive. And confounding. And infuriating. But here we are.

A Duplicated Recipe?

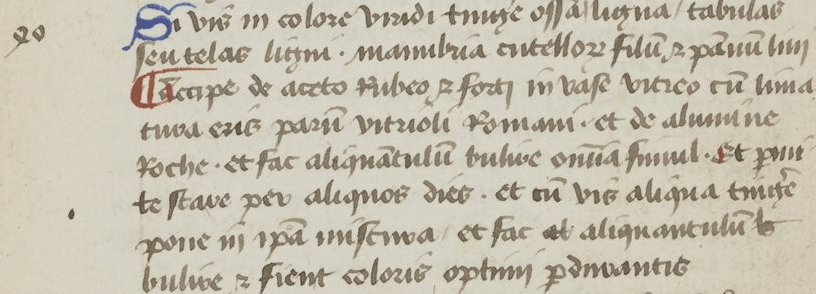

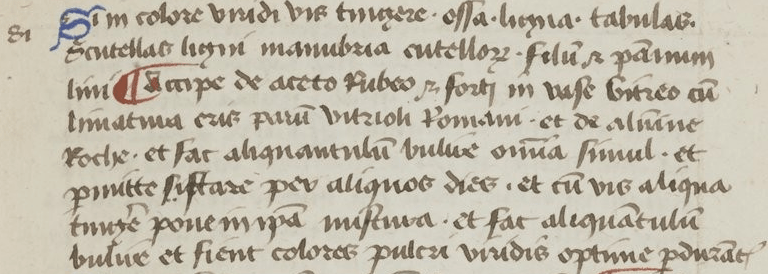

Villela-Petit (in “Copies, Reworkings, and Renewals”) points out (p.170) that Alcherio accidentally copied the same recipe from Brother Dionysus twice (“Si vis in colore viridi tingere ossa, ligna, tabulas, scutellas ligni, manubria cutellorum, filum et pannum lini“, recipes 40 and 81), though with the second word (“vis”) misplaced and a few minor spelling differences:

To be fair, I expect that Brother Dionysus himself had copied the two by mistake, and that Alcherio and le Begue retained the duplicate in their scrupulously copied copies.

Might there be a similar duplicated recipe anywhere in Q20? Having access to the same source text that has been manipulated in two different ways within the same overall system may well be extremely revealing, cryptologically speaking, like a kind of “internal Rosetta Stone”.

We’d be looking for a single-paragraph recipe where the title is about 25% of the length of the paragraph (2 lines out of eight). #40 is the third of three slightly longer paragraphs in the middle of medium-sized paragraphs (6.5 6.5 6 // 10 8 8.5 // 6 5.5 11, while #81 is the first of three slightly longer paragraphs after three short paragraphs (3.5 5.5 4 // 8 8 9.5 // 3 4 7).

Generally, I’d expect to see a Voynichese paragraph about five or six lines long, like this one (on f103v):

However, I must confess that I struggled to find even one paragraph (let alone two) that met all (or even most) of the criteria I had in mind. I’ll revisit this in a few days’ time (when I have a clearer head).

Thoughts, Nick?

I think it’s fair to say that the way I’ve previously described block paradigm attacks has been fairly abstract and non-specific: but it is actually something a bit tricksier than just a ‘known plaintext attack’. Rather, it’s more like a kind of scribal jigsaw puzzle, where you’re hoping to glimpse some sign of a scribal structure or ‘meta-pattern’ peeking through the edges of whatever confuddlery has been applied to its plaintext. This post is hopefully only the beginning, I suspect it will take a while to really get under Q20’s skin.

As always, our attacks have all the less ‘bite’ for not having managed to reconstruct more of the original state of the manuscript. Villela-Petit was even able to reconstruct various aspects of the original state of Brother Dionysus’ two gatherings (p.170), but frankly we have a long way to go to catch up with that level of reconstruction.

Recently Peter M commented “The VM doesn’t look like alchemy to me either. The symbols for metals and chemicals are missing.” and Diane replied “specialists in early modern alchemical imagery have said pretty plainly that there’s none of that in the Vms”. Yes, there does not appear to be any “symbols for metals “..”, at least to our 21st Century eyes. But I see abundant examples of things in the VMs that were of interest to alchemists. And not all alchemical books contain the alchemical symbols for metals or chemicals. For instance, look at the Rosarium Philosophorum (RP) and there is not a single instance of a metal or chemical symbol. But Wikipedia notes that this text “is recognised as one of the most important texts of European alchemy.”

I note that the RP does contain three hundred instances of the word “water” and other instances relating to water such as “washed” and “washing”. It also contains two hundred and eighty five instances of the word “sol” and fifty eight instances of the word “luna”, as well as illustrations showing water and water associated activities, and the sun and moon. Thus, these things are of importance in alchemical thinking. The Vms contains many illustrations of water and water based activities, and of the sun and the moon and I think their prominence in the Vms suggests that at least part of the Vms was alchemically inspired.

Does it matter? Well, yes because this suggests that a place to look for a block of text with which to fit against the text of the Vms might be found in alchemical texts. Regarding the possible poem on f81r of the Vms perhaps we should look for alchemically related poems predating circa 1450.

However, alchemical related poems pre-c1450 appear to be scarce, but alchemy deals with a lot of recipes and these would generally be the things that would be encoded, even in a private work book.

Lack of comments to this post confirm that if Voynich studies isn’t dead, it’s gone dark.. or you know, sort of Bostonian-Lodge.

““Here’s to the town of Boston, The land of the bean and the cod, Where the Lowells speak only to Cabots, And the Cabots speak only to God.”

Diane: if I was posting for likes, this post would have had a picture of a kitten wearing a Santa hat. 😐

hahahaha.

Happy Christmas to you, Nick, and to all your subscribers.

Byron Deveson

Ad vocem of what you wrote:

“Recently Peter M commented “The VM doesn’t look like alchemy to me either. The symbols for metals and chemicals are missing.” and Diane replied “specialists in early modern alchemical imagery have said pretty plainly that there’s none of that in the Vms”.”

The claim that the Voynich Manuscript does not contain alchemical symbols, in my opinion, is not true. Right after that, in the next sentence you wrote that “Yes, there does not appear to be any “symbols for metals “..”, at least to our 21st Century eyes.”

This is also not 100% true. Of course, it is difficult to find symbols for planetary metals, but from the point of view of those people who created this work, it would not make the slightest sense – and this would be because of decoding the hidden contents of the Manuscript too quickly, and it would also shed too much “light” on who potentially could be its author – and in particular which circles.

And the fact that these are Alchemical-Gnostic circles is evidenced by other alchemical symbols, of which there are even a lot in the Voynich Manuscript.

Such alchemical symbols, in my opinion, can be found in the section colloquially called Astronomical – from folio 67R to 68V, which in their symbolism encode information of the same type as known as the Four basic elements, and also an equally important one: the Diagram of the Ophites. Surely these are “alchemical symbols”?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alchemical_symbol

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ophite_Diagrams

I have looked at the pages where they specifically mention. However, I cannot find any alchemical symbols.

What do I understand by the symbols in your link.

Basically, I think that various signs, if I were to consider them alchemical, may not appear elsewhere in words.

Accordingly, you will have to explain to me exactly what alchemical symbols are in VM.

Grzegorz,

You may like to spend some time thinking through your ideas. For example, there’s a distinction between ‘alchemical imagery’ and ‘alchemical symbols’.

I think one also has to be careful to avoid the basic mistake of supposing that if something turns up in one context, it occurs in no other time, place or context.

So, for example with the alchemical symbols you mention (not alchemical imagery as such), we see that silver is denoted by the symbol for the moon’s crescent. The symbol is not ‘an alchemical symbol’ so much as form used in almost every culture and time, but which the western alchemists decided to employ in their own shorthand. So if there is a ‘lunar crescent’ shape in one of the Voynich drawings, you cannot say “aha! the whole manuscript is about alchemy’ – or even ‘this drawing is about alchemy’.

Similarly, a circle containing smaller circles is just a diagram. Depending on what the maker links to those circles, the sense of the diagram will be entirely different and though diagrams of such a kind might have been (*might* – the drawing is an imaginative reconstruction) Orphite, it doesn’t mean all such diagrams were the sole possession of Orphite sects, or their presence in the Vms (though there are none of that kind) would be any indication of Orphite influence.

In fact, Rich Santacoloma first identified a certain drawing in the manuscript as a reference to the elements. Independently I came to a similar but not identical conclusion, because he had assumed the system would be the European, and I had found that it could not be that system by the number and order of the elements referenced. And just to keep a little mystery about it, I won’t specify the page on which that diagram appears. Happy Christmas. 😀

Peter M.

With all due respect, but I’m old enough now that I don’t have to explain anything anymore, at least I could. Besides, it seems to me that without giving you the context and comprehensive knowledge of the subject, you wouldn’t understand it anyway. That’s not to say I’m avoiding some broader response on this topic, but this is not the time to do so – as I would like to publicize topics related to other sections of the Voynich Manuscript beforehand.

After all, I have already clearly written that the knowledge of the Four Basic Elements and the Diagram of the Ophites are hidden in the foils I have mentioned.

Western alchemy makes use of the four classical elements. The symbols used for these are:

Air 🜁 (Air symbol (alchemical).svg)

Earth 🜃 (Earth symbol (alchemical).svg)

Fire 🜂 (Fire symbol (alchemical).svg)

Water 🜄 (Water symbol (alchemical).svg)

Diane

What you say in the first paragraph is somewhat correct.

Has anybody out there read Paulo Coelho’s Alchemist in a language other than mainstream. The Vietnamese (Gia Kim) edition puts a somewhat different slant on identifing and interdicting with the main A E F W symbols? If so you might also be aware that both the VM and Tieng Viet language comprise short words that also appear to be quite repetitious, if the accents are disregarded.

Grzegorz,

Thank you.

@Grzegorz Ostrowski

If you do not want to or cannot explain something, it is only an idea and has no value.

And when you mention that you are old enough, which was not an issue, that tells me that you are not old enough.

John Sanders. So I contacted a Vietnamese man yesterday. I showed him a few pages from the manuscript. There are a lot of Vietnamese here. They sell just about anything that can be sold. It’s called Sony. He’s a friend. So I say to him, Sony, look at this image and font. He looked at it for about 30 minutes. He rolled his eyes and muttered something under his breath. Then he said Well, this is not written in Vietnamese at all. I would know that right away. Unfortunately, this is a mystery even for me as a Vietnamese, but I will write home to Vietnam. Brother is quite smart. His grandfather was Ho Chi Minh, so he will certainly know a lot. So I have to wait for an answer. I’ll let you know then. Hi.