Searching for “W. M. Richards” (who took “A splendid view of the triple-connected meteor”) following my last post, it struck me that that person might well have been an astronomer. Though it seems Richards wasn’t, this hunch quickly led me to the Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific for 1896, which contained a section on the “Meteor of October 22 1896“, which is what the good folk of that society called the phenomenon that was widely observed on 22 Oct 1896.

Even though some of this overlaps with what I have previously posted, I think that the entirety (pp.324-326) bears reproducing in full.

Note that “CDP” was Professor C. D. Perrine, Director of the Lick Observatory: hence if you wish to see the actual letters to Professor Perrine transcribed below (hopefully with the omitted sketches), I believe you should go to the Lick Observatory Records at UC Santa Cruz. Having said that, I don’t believe any of the 148.5 linear feet of correspondence in the archives there (UA.036.Ser.01) has yet been digitised (bah). Though I am (of course) going to ask if they can retrieve the two drawings omitted from the text for me.

Meteor Seen at Noon (November 1).

A meteor, leaving a broad scintillating track, traversed fifteen degrees of the northwestern heavens at about ten minutes past noon yesterday. It was seen at a point about thirty degrees above the horizon, and the half second of its flight shone as an electric light. The shooting star was seen by a visitor at the Park, in San Francisco. – S. F. Chronicle, November 2.

A Bright Meteor Seen on October 8, 1896.

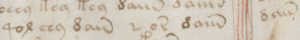

Mr. P. Perrine, of Alameda, reports a meteor four or five times as bright as Venus on October 8, 1896, at 7h 32m p.m. It was of a brilliant white color and moved rapidly from an altitude of about thirty degrees to near the horizon, inclining toward the east at an angle of about forty-five degrees. C. D. P.

The Meteor of October 22 1896

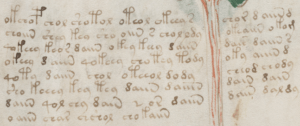

In the evening of October 22d, while in Oakland, I saw an unusually interesting meteor. I first saw it a little north of west, where it seemed to rise like a sky-rocket, which it so much resembled that at first I had no thought of its true character. Its apparent motion after the first few seconds was almost exactly parallel to my horizon. At first sight the head appeared to be single, but after two or three seconds (during which time it rapidly increased in brightness), it separated into four parts but not with the usual explosive effect, for all the parts pursued the same course in a straight line, each leaving its train of sparks which reached to the next part, a long train following all. The last portion was much the faintest and soon disappeared, while the remaining three were of more nearly equal brightness, the first being somewhal brighter than the others.

After traversing an arc of ninety degrees or more, they all disappeared at 6h 9m 30″ ± 10″ P. S. T. in the smoke of the city and behind the Berkeley hills. When at their brightest, each portion considerably surpassed Venus in brilliancy.

The apparent motion was remarkably slow, the meteor being visible for about ten seconds.

C. D. Perrine.

Mount Hamilton, October 31, 1896.

Abstract of a Letter from Mr. D. J. Brown to Professor Holden.

“Last Camp,” Napa, October 23, 1896.

“At about six o’clock, p.m. yesterday, there appeared in this vicinity a meteor of such remarkable appearance that I deem it proper to report its passage to you.

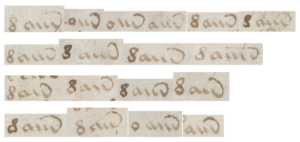

“It came from the west — its flight was quite near the Earth, and speed slower than that of any other like body I have ever seen. At first it had a solid head, with a train of considerable length. Soon this head divided into three parts, presenting an appearance like this, [the sketch is omitted] slowly passing over the valley in the direction of Napa Soda Springs. It went to pieces like a spent sky-rocket.”

Letter from Mr. H. F. Stivers, at Hunter’s, Tehama County, Cal., October 26, 1896.

“Seeing a meteor, the other evening, that appeared to me more than ordinary, I have roughly sketched [the sketch is omitted] and described its appearance and would be pleased to know if it was seen at the Observatory. Friday, October 22d, at 6:10 p. m., P. S. T., I saw a very brilliant meteor in the west. My attention was drawn to it by the great light it gave. At first view it was not more than fifteen or twenty degrees above the western horizon. It sailed majestically along like an immense rocket directly towards the Moon, and disappeared in the Moon’s light, not more than ten degrees from that luminary. Its zenith was about ten degrees north of mine, on passing which it separated twice, making plainly visible three pieces, the largest the apparent size of a closed hand, the others diminished to about one-half each.

“It was visible from ten to fifteen seconds, and had a trail of twenty-five or thirty degrees.

“It emitted a white light, tinged at times, I should judge, with red and yellow. It must have described the complete arc of the heavens and had it not been for the brightness of the full moon, should nearly all have been observable by me.”

Wheatland, [Yuba County] October 22. — A most remarkable meteor was seen a few minutes past 6 o’clock this evening. It appeared in the west as a star of the magnitude of the evening star, and in close proximity to Jupiter. [i.e. Venus] It increased in size and gradually separated, first into two and finally into three distinct comet-shaped bodies. Following each other they sped toward the east and disappeared. — S. F. Chronicle

Highland Springs, October 23. — At 6:13 o’clock, last night, a meteoric display, such as is seldom seen, passed over here. It was composed of three large balls of fire moving from southwest to northeast. It looked as if the balls burst on the mountain north of Clear Lake.

Three Meteors in Line.

Nevada, Cal., October 22. — A triple connected meteor was observed in the northern heavens at ten minutes past 6 o’clock this evening. Three balls of fire, all in a row and connected like a train of cars, with a long fiery tail, flashed in view just a few degrees above the western horizon and traveled in a direction a little north of east. In half a minute they disappeared from view high in the heavens, apparently somewhere over the Great Dipper and North Star.

The sight was magnificent and awe-inspiring, and one long to be remembered, as it did not appear to be over forty or fifty miles above the earth. A splendid view of the triple-connected meteor was taken by W. M. Richards. — S. F. Examiner, Oct. 23, 1896.

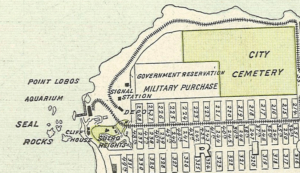

This meteor was also seen by many visitors at the Cliff House, near San Francisco.