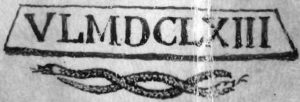

The first ‘La Buse’ cryptogram was first described (and indeed ably decrypted) by Charles de la Roncière in his 1934 book “Le Flibustier Mysterieux”. Though only 17 lines long, the decryption was – though correct without any real doubt – as mysterious as the pirate of the book’s title.

Annoyingly, de la Roncière didn’t give sources for any of his evidence, almost all of which seemed to be tied up with French treasure hunters; much of his secondary narrative (e.g. about Le Butin) has yet to have a single external document verifying it; and his whole narrative is wrapped up with a fair few unsubstantiated myths and legends which seem to have appeared in his book for the first time anywhere.

Why did this sober and exceptionally well-respected historian get himself tangled up with this mess? What was going on back then? Seventy years on, there’s still no good answer for any such questions: the only people who think this could be real are treasure hunters (who want all treasure to be real, basically) and skeptical code-breakers (such as myself, who suspect the cryptogram might be genuine, even if the proposed link with La Buse itself is almost certainly spurious).

And then you have the second ‘La Buse’ cryptogram, the first image of which was first put on the Internet (I believe) by Yannick Benaben about a decade ago, as part of a La Buse-themed fiction he was writing. Though this has its cadre of true believers (such Emmanuel Mezino, whose book about it lurches violently between the twin cipher poles of clear-headed accuracy and woefully empty speculation), my own conclusion is that it is, if anything, even more confused than the first cryptogram.

This second cryptogram has an extra five lines of encrypted text appended to (broadly) the same 17-line cryptogram, using (broadly) the same pigpen cipher key: but whereas the decrypted cleartext of the first 17 lines makes essentially no sense at all, the extra lines shine through clear as a bell.

My cryptographic conclusion was this these extra lines were surely an extra layer, added at a later date (and by a completely different owner), i.e. that these are “super-marginalia”, added in for reasons unknown… though I tentatively predicted that it was to try to link the underlying 17-line cryptogram more definitively with the piratically successful (but ultimately hanged) Olivier Levasseur.

All of which was no more than an appetiser.

Because this was where online commenter CptEvil came in.

The Gold Bug

CptEvil noted that if you compare the start of the last five lines of the second La Buse cryptogram…

un bon verre dans l’hostel de le veque dant(S)

le siege du diable r(Q)uarar(N)te siz(X) degrès

f(S)iz(X) minutes deuz(X) fois

pour celui qui le decouvrira

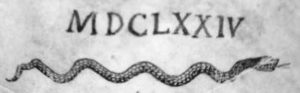

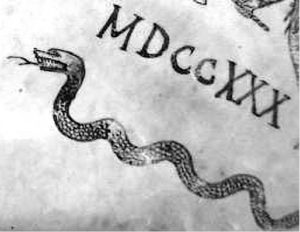

juillet mil sept cent (T)rente

(…in English…)

a good drink in the bishop’s hostel in

the devil’s seat forty six degrees

six minutes two times

for the person who will discover it

july 1730

…with the cryptogram used by Edgar Allan Poe in his famous short story “The Gold Bug”, you discover something rather extraordinary:-

A good glass in the bishop’s hostel in the devil’s seat

— twenty-one degrees and thirteen minutes

— northeast and by north

— main branch seventh limb east side

— shoot from the left eye of the death’s-head

— a bee line from the tree through the shot fifty feet out.

(Note that this was also suggested elsewhere on the web back in March 2015 by online commenter “indi”.)

Are these two cryptograms connected? Why, yes, they most surely are. But how? That’s far more difficult to answer than you might think, even though we probably only have three main scenarios to consider:-

(1) Did Poe Make Both Cryptograms?

Even though there are plenty of people who assert that Poe made the Beale Papers, I’ve yet to see any evidence beyond mere handwavery that this is so. And the same would seem to be true here… but yet the two cryptograms are connected.

(2) Was “The Gold Bug” The Second Cryptogram’s Source?

Interestingly, Baudelaire’s famous (1856) French translation of The Gold Bug (as CptEvil noted in a follow-up comment) uses “la chaise” to translate “seat”, whereas “le siege” only appears in a 1933 translation. Which would tend to suggest that if the second cryptogram was in some way a copy of Poe’s cryptogram (which, after all, was embedded in a pirate fantasy about discovering Captain Kidd’s treasure), it was probably made after 1933.

(PS: how did Alphonse Borghers translate this in 1845?)

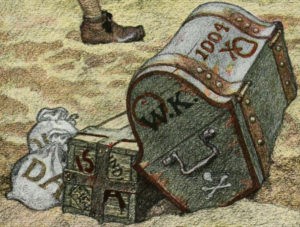

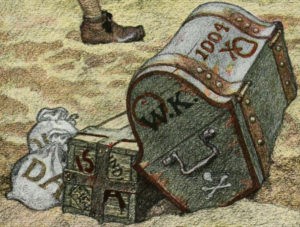

CptEvil also points out that there is a distinct similarity between the treasure chest depicted in the second cryptogram…

…and a fantasy treasure chest famously depicted by Victorian illustrator Howard Pyle:

(This was also pointed out by online commenter “marc” later in March 2015.)

Note in particular the “XO” motif on the lid of the chest and the structural similarity of the square chest just to the left of the main chest: all of which would seem to be a giveaway, particularly as Howard Pyle seems to have made up almost everything he drew to do with pirates. (Indeed, most of Johnny Depp’s “Jack Sparrow” on-board piratical style seems to have been plucked directly from the Howard Pyle play-book, more than a century later).

And yet… just as we can’t (yet) rule out Poe having seen this second cryptogram, we can’t rule out Pyle having seen it either. And we also can’t (without a huge investment in time in tracking down the iconography of treasure chests) rules out the possibilities (a) that Pyle copied it from the second cryptogram, or (b) that Pyle and the second cryptogram’s author were both strongly influenced by the same image, perhaps found in an old pirate book.

Moreover, inserting a line from “The Gold Bug” would seem like quite a ridiculous thing to do if the overall intention was to make the cryptogram seem to date from 1730, given that Poe wrote his short story more than a century after Olivier Levasseur died. This fails the test of good sense, surely?

(3) Was The Second Cryptogram “The Gold Bug”‘s Source?

Between December 1839 and May 1840, Edgar Allan Poe wrote a series of articles in Alexander’s Weekly Messenger, in many of which he decrypted readers’ cryptograms. You can also trace aspects of these exchanges in Poe’s letters.

Rather more substantial is Poe’s A Few Words On Secret Writing from Graham’s Magazine in July 1841, though I should add that William Friedman didn’t think much of Poe’s non-systematic attempts at decryption (see p.41ff of this 1937 Signal Corps magazine).

From his correspondence, we know that by 1842 Poe had lost interest in decrypting the approximately one hundred reader’s cryptograms that even then still continued to crash on his beach, and in some of which “Foreign languages were employed”: and yet in 1843, his “The Gold Bug” played directly to that same audience on the same mysterious vein, with wild success. Poe also refers to a book in French on cryptography by Jean-Francois Niceron (though Niceron lived a century before La Buse): so it is entirely possible that Poe had contact with a French cryptographer of his era.

It seems entirely possible, then, that Poe might have been directly inspired by an encounter with the second cryptogram (or something exceedingly like it), to the point that he shaped his story around it. For are they not both pitched as pirate treasure narratives, with an exceedingly obscure key?

(Note that David Kahn, who likes The Gold Bug despite the fact that it is “full of absurdities and errors”, suggests in “The Codebreakers” that Poe may well have borrowed the basic Captain-Kidd-treasure-hunting plot from Robert M. Bird’s novel “Sheppard Lee”, a book Poe had previously reviewed – apparently, all you need to do is dream how to get to the treasure the same way three nights in a row, etc etc.)

But the single observation that most makes me suspect that Poe had seen the second “La Buse” cryptogram is simply that the plaintext revealed by his protagonist’s decryption makes no sense, even as a novelistic device. His cryptologic hero Legrand eventually makes sense of “Bishop’s Hostel” as “Bessop’s Castle”, which didn’t really make any sense to me when I first read the story many decades ago, and – frankly – still doesn’t ring even remotely true today.

So could it be that Poe actually constructed the story backwards from the phrase “A good glass in the bishop’s hostel in the devil’s seat”? If so, what does the phrase actually mean?

The most (in)famous Devil’s Seat of recent years is the “Fauteuil du Diable” (“Devil’s Armchair”) at Rennes-les-Bains, which somehow got entwined with the whole ludicrous “Priory of Sion” fantasy. But The Gold Bug would seem to have preceded that by many decades, so we can perhaps move swiftly past it. 🙂

It has been suggested that this in fact refers to the formerly-volcanic piton (mountain) on Réunion Island: though possible, this seems to be wading knee-deep in the inky waters of speculation. But beyond that, I’m kind of out of ideas.

All the same, the notion that “The Devil’s Seat” at “forty six degrees six minutes two times” (presumbly longitude measured east from Paris?) refers to a formerly-volcanic piton seems more probable to me than the notion that Poe plucked the phrase “A good glass in the bishop’s hostel in the devil’s seat” from the ether entirely a propos of nothing, even if he did dream it three nights in a row. But even so, I’d prefer to have even a soupcon of solid evidence either way, this is still all a bit too messy for my liking. 🙂