I know, I know, it somehow turned into ‘Beale Cipher Week’ here at Cipher Mysteries without so much as a tiny red flag on my part by way of warning. Having said that, I’m just as surprised as you probably are, and yes, I do have plenty of non-Beale cipher stuff to cover: but stick with where this is all heading, I think it’s actually quite interesting.

While waiting for my Thomas Beale Junior-related books to arrive (yes, the virtual BealeFest Will Continue), I had a quick look around the web to see if anything else Bealesque was going on. Apart from an online comic-book retelling of the Beale pamphlet / myth, all I found of interest was Reddit user called HughJorgens (fnarr fnarr) asserting that, contrary to what Ward’s pamphlet claims, you don’t get gold and silver mines in the same place.

Might he be right? I didn’t know: but given that the pamphlet specifically claims that Beale’s group found gold and silver north of Santa Fe, I thought it would be useful to briefly review gold and silver mining, and also the specific history of gold and silver mining in Colorado and New Mexico.

Lode vs Vein vs Placer vs Bench

To make sense of what’s going on here, you have to know some gold prospector terminology: so here’s a brief guide.

Gold starts in lodes (rich, clumpy underground deposits, typically in hard rock that needs mining out): but when a river cuts its way through an underground deposit, it breaks fragments of gold away from the lode, and washes them away. If they sink into fissures in the rock, they form underground gold veins (spread out in long thin deposits), or else they get carried away into stream beds containing sand, gravel or earth, known as placers. (Because gold is roughly six or so times more dense than most other materials normally found in a placer, it tends to move more slowly, to fall and then to get wedged in cracks in the bottom of the stream bed.)

Finally… when a stream or river changes its course over the course of time, an old stream bed can be left (quite literally) ‘high and dry’. This is known as a ‘bench’: and the gold found in a bench is a bench deposit. But if you’re looking at bench deposits, you need to dry wash what you dig from the bench, a process that was invented in 1897 by Thomas Edison – before that, prospectors had to bring lots of water with them to wet wash what they had dug out.

So: to successfully pan for gold, you need to be standing on a placer deposit, though ambitious gold prospectors sometimes try to trace a stream-bed back to the lode or veins where the gold in the placer was originally washed away from.

Silver prospecting, however, works quite differently from all this, because silver almost never appears as a placer deposit or bench deposit in the way that gold is, but instead usually appears as ore that needs mining. Moreover, silver ore is also frequently found with various other commercially valuable ores – copper, lead, tin – so offers much more of a conventional mining ‘win’ than gold. Hence a ‘gold rush’ can be a short, sharp shock to a local economy that then quickly disappears, whereas a ‘silver’ rush takes much longer to work through, often decades.

Colorado

In 1859, the first gold in Colorado was found in placer deposits in Cherry Creek, near where it meets the South Platte River. This triggered a Colorado gold rush (known as the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush simply because it was a well-known local feature, not because the gold was anywhere near it), which was followed by vein discoveries in a number of locations.

The earliest guide to the history of Colorado Gold was published in 1859 by Le Roy Reuben Hafen. His “The Illustrated Miners’ Hand-book and Guide to Pike’s Peak: With a New and Reliable Map, Showing All the Routes and the Gold Regions of Western Kansas and Nebraska” (available online here, though sadly without a scan of his “New and Reliable Map”) include some interesting (if somewhat breathless and unreliable-sounding) stories, such as this one:

In 1835, a French Trapper by the name of Eustace Carriere, while lost from his party, wandered through that region for several weeks, during which time he collected some fine specimiens, which he found lying upon the surface, and took them with him to New Mexico. Upon examination, they proved to be pure gold, and a company, with M. Carriere as their guide, soon set out for the new Eldorado. Arriving there, their guide failed to find the precise location where he had seen so much of the “sparkling mineral,” and the Mexicans, under the supposition that he did not wish to disclose to them his new discovery, inflicted upon him a severe whipping, left him, and returned to New Mexico. (p.7)

Not long after gold was ‘properly’ discovered in Colorado in 1859, silver veins too were found in the Central City-Idaho Springs district. Interestingly, “[the] veins of the district are zoned in a roughly concentric manner, with gold-bearing pyrite veins in the center, and silver-bearing galena veins more common in the outlying areas.”

New Mexico

In New Mexico, gold was first discovered in 1828, several decades earlier than in Colorado. Placer deposits were found first (in the Ortiz mountains in Santa Fe County), followed by a lode deposit close by, five years later (in 1833), which was still 13 years before it was incorporated into the United States. Yet New Mexico’s ultra-dry climate made it a difficult place to prospect for gold, particularly in the years before drywashers became available.

Fayette Jones’ (1905) book New Mexico Mines and Minerals talks about stories of old mines in the area, but concludes:

The evidence seems conclusive that no mines of either silver or gold were worked to any extent prior to 1800; save some little gold picked from the gravels at various points throughout the Territory and from the silver lead mines in the vicinity of Los Cerrillos […] (pp.11-12)

Another choice quotation (from what I found a very interesting book) concerned the gold productivity of the whole New Mexico territory at this time:

According to Prince’s History of New Mexico, between $60,000 and $80,000 in gold was taken out annually between the years 1832 and 1835. The poorest years of this period were from $30,000 to $40,000. (p.22)

Thomas Beale’s Gold and Silver?

In Ward’s 1885 pamphlet, the author writes that when Beale’s party found gold “in a small ravine […] in a cleft of the rocks” in April or May of 1818, it was “some 250 or 300 miles to the north of Santa Fe”, i.e. in the middle of modern-day Colorado. “[The] work progressed favorable for eighteen months or more, and a great deal of gold had accumulated in my hands as well as silver, which had likewise been found.”

Yet it looks as though HughJorgens’ (sigh) claim that gold and silver don’t occur together isn’t entirely true, in that both were indeed found close by each other in Central City-Idaho Springs (though only in 1859, and in veins rather than in lodes). And in fact Idaho Springs is very nearly directly north of Santa Fe (the two are about 340 miles apart).

But what bothers me here is the sheer scale of the operation, particularly the silver. The problem with mining silver is that that’s the easy part: it then has to be smelted in order to be commercially useful. But without a silver industry already in place, there wouldn’t be any kind of silver smelting infrastructure in place. Colorado may have become known for a while in the late 19th century as the Silver State, but circa 1820, this was all a long way in the future.

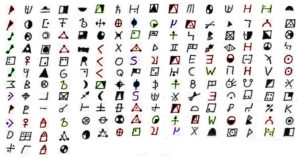

According to the B2 ciphertext:

“The first deposit consisted of one thousand and fourteen pounds of gold, and three thousand eight hundred and twelve pounds of silver, deposited November, 1819. The second was made December, 1821, and consisted of nineteen hundred and seven pounds of gold, and twelve hundred and eighty-eight pounds of silver; also jewels, obtained in St. Louis in exchange for silver to save transportation, and valued at $13,000.”

I don’t know: there are a lot of details here that I can’t quite swallow all at the same time. If it’s right, Beale and his team not only found gold (in vastly greater quantity than Eustace Carriere claimed to have done in 1835), but they also found silver, which is an extremely rare combination. They also seem to have found lode deposits near the surface: the description doesn’t sound as though they were doing anything so gauche as panning at placer deposits. And they also seem to have exchanged a large amount of silver (presumably silver ore?) in St Louis without causing any ripples of suspicion there.

Whether or not you buy into the whole ‘thirty gentlemen adventurers’ story is up to you: but there’s something about all this gold and silver business that mechanically and physically doesn’t ring true to me. It’s a thousand-plus miles to St Louis from Santa Fe: that’s a long, long way to haul that stuff, really it is. 🙁