I was mooching round the British Academy’s website a little earlier (I was trying to find the Neil Ker Memorial Fund, which I had forgotten the name of), when I noticed its page on British Academy Conferences – this is where ‘any’ UK citizen can propose a conference on any subject (as long as they’re prepared to run it themselves, and don’t mind being turned down with no reason being given).

And so the (as yet hypothetical) question naturally follows: if I was organizing a British Academy-hosted conference on the Voynich Manuscript, how would I approach the challenge? What should that kind of Voynich Manuscript conference look like?

What Isn’t Worth Looking At

It’s easy enough to list all the things I wouldn’t want to let onto the podium:

* Voynich theories [– too boring for words –]

* Voynich metatheories [– too sad for words –]

* Voynich iconography / iconology [– too free-floating for words –]

* Voynich linguistics [– sorry, but it’s just not written in an obscure language –]

* Voynich cryptology [– sorry, but it’s just not written in any obviously categorisable cipher –]

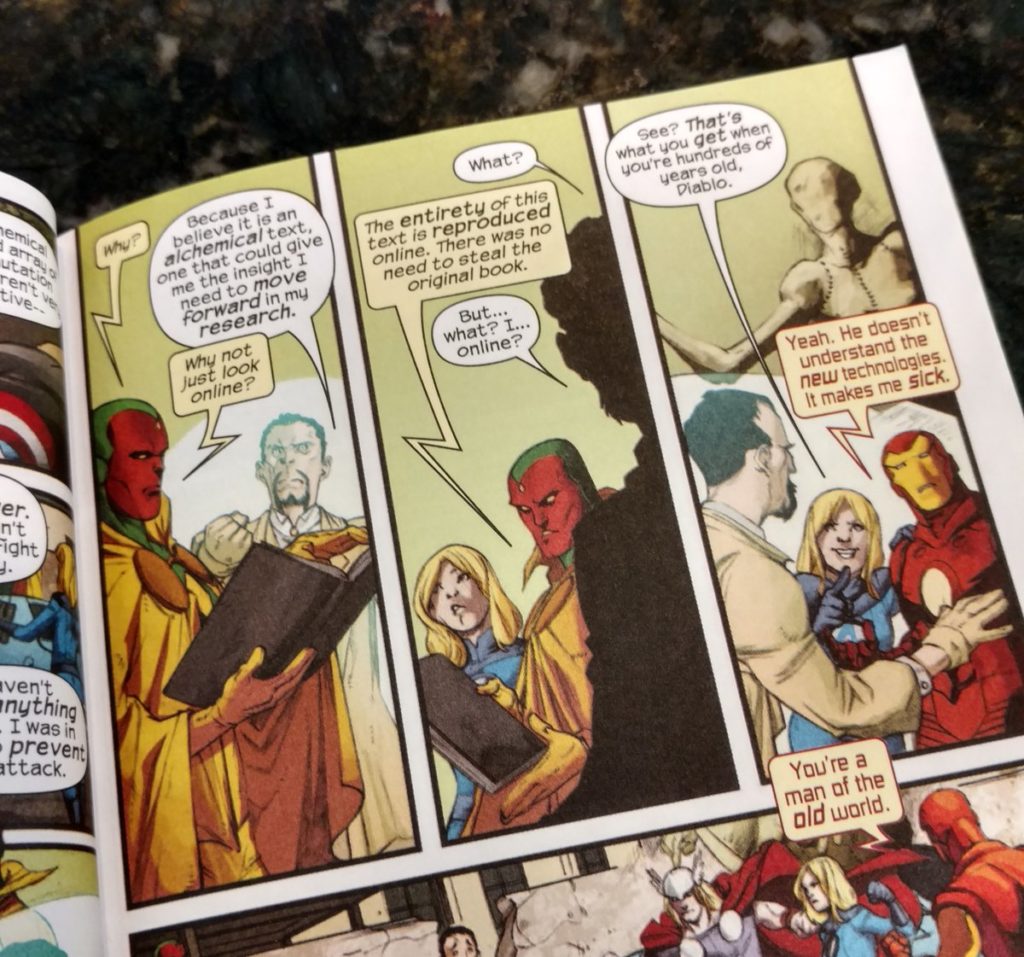

Some may be surprised that I would exclude both Voynich linguistics and Voynich cryptology. The simple reason for this is that I very strongly believe that we still don’t know enough about the Voynich’s basics to do meaningful analysis about either. For example, the existence of “Neal Key”-like behaviour offers a strong counter-argument not only against any kind of simple-minded linguistic take, but also against any kind of straightforward substitution cipher argument derived from a reading of cryptographic history.

The only reference to fifteenth century non-syllabic transposition ciphers I know of is a brief passage in Alberti’s book which I read as a reported speech account of a debate between Alberti and a transposition cipher practitioner. There is (unless you know better) not even one pre-1500 non-syllabic transposition cipher cryptogram still extant.

And so Voynich research is still in a position where neither linguistic approaches nor historical cryptological approaches have any ‘moral high ground’ to argue their respective cases. The Voynich Manuscript laughs pityingly at both camps’ feeble efforts.

So… what would I want attendees to be discussing, then?

The Joy Of The Concrete

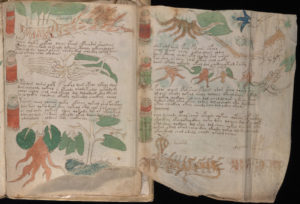

As per my recent list of 100 Voynich (research) problems, there remains – despite all the excellent work that has been done since the Beinecke first released digital scans in 2004 – a huge amount of fundamental stuff that we still don’t know about the Voynich Manuscript.

The problem with not knowing how pages, paragraphs, lines, words, and even letters were constructed at a really basic level is that this makes it extremely difficult to know whether our transcriptions are a help or a hindrance. What order were lines written? (Philip Neal points to evidence that some line interleaving may have taken place in at least Q20.) What order were strokes in letters written? (Back in 2006 in “Curse”, I pointed to evidence that on some pages, the terminal EVA ‘n’ stroke of ‘daiin’ may have been added as a separate pass). And so forth.

Hence the core stuff I would want conference attendees to focus on is purely that-which-is-concrete: things that can be seen, highlighted, measured, cross-referenced, scanned, indexed, counted, etc. What were the original gatherings and their nesting orders? What happened to those gatherings to turn them into quires? What construction stages can we solidly identify? (There must be close to twenty of them, is my current best estimate). Can we order (or even date) these construction stages? What, ultimately, was the alpha state of the manuscript?

But this isn’t just a matter of assembling some codicological dream-team (even though many of the most basic unanswered questions are clearly codicological in nature). There’s also the tricky matter of the Currier Hands and the f116v marginalia (which would require a great deal of palaeographical expertise to untangle): and also the taxing matter of the differences between the various Currier languages, which is something closer to meta-linguistics than linguistics per se.

In all cases, the central include-it/don’t-include-it criterion would be whether any given analysis would advance our knowledge of the Voynich without having to assume any given historical narrative or theory far beyond the basic radiocarbon dating.

Never mind being carbon-neutral, could such a conference be theory-neutral? My hope is that it could, but I do appreciate that this is something many Voynich researchers could easily find difficult to work to, or to achieve.

Linguistics vs meta-linguistics

I think it’s fair to say that the long-term relationship between Voynich research and Voynich linguistic research has not been greatly productive. Given that the mainstream Voynich research position has for more than fifty years been that Voynichese is simply not a “language” in any straightforward sense of the term, it is dispiriting to see Stephen Bax continually raking over the same barren concrete surface, ever-announcing to the world that the few motes of dust he has accumulated do in fact do actually form the basis of some über-obscure hybridized historical linguistic system over and above mere statistical chance.

Would out-and-out linguistics researchers such as Stephen Bax be welcome at such a conference? With the putative roles reversed, Bax has certainly made it clear online that mainstream Voynich researchers (errrm… particularly me, it would seem) would be distinctly unwelcome at any Voynich-themed seminar he would organize.

But what annoys me so much about Bax isn’t that what he puts forward is just plain wrong (even though it is), but that by mistakenly telling all and sundry that the challenge of Voynichese is one where its beginning, middle and end all fall inside a purely linguistic domain, he utterly misrepresents the specific difficulties it poses.

Rather, what Voynichese does present to researchers is an overlapping combination of linguistics (e.g. actual language content), meta-linguistics (content transformation, e.g. abbreviations, codes, and transposition), and misdirection (e.g. substitution and steganography). Hence the primary difficulty we face with Voynichese is more one of determining its internal boundaries: what is misdirection, what is language, and what is meta-linguistics? If Voynich linguistic researchers could successfully accept that this question is the real one we need to answer before trying to push forward, then perhaps we could all start to work together in a reasonably productive way.

So I have to say I’m hugely encouraged that at least one Voynich linguistics researcher out there (Emma May Smith) has recently started looking in a genuinely agnostic way at all the difficult stuff that confounds those who try to stick to fairly simple-minded linguistics accounts. If only more linguistics researchers followed her example. *sigh*

Raman Imaging

There is a final twist: in the ideal world of my imagination, the conference stage would be part-laboratory too, with a live link between a Raman imaging device in New Haven looking at a series of pages of the Voynich Manuscript, sometimes through a microscope. The conference attendees would be able to discuss and propose different tests live, so that they could see “under the skin” (sometimes literally) of the manuscript.

But once you throw that into the mix, would this even qualify as a “conference” any more? Or would it actually be closer to some kind of Reality TV historical research happening, in a way that’s so acutely of-the-moment that it hasn’t even got its own annoying hashtag yet?

Put that way, should I be thinking in terms not of the British Academy, but of Channel 4 and Smithsonian TV?