Hot off the Cryptologia presses comes news of Levente Zoltán Király & Gábor Tokai’s (2018) paper “Cracking the code of the Rohonc Codex” (Cryptologia, 42:4, 285-315, DOI: 10.1080/01611194.2018.1449147). This is part of a long series of papers and articles the two authors have been putting out that try to explain different technical aspects of the Rohonc Codex decryption they have been developing (though they initially started independently), and which Hungarian uber-crypto-guy Benedek Láng has favourably mentioned a number of times.

I now have a copy of the paper (which Lev Király kindly passed me) and have spent the last few days combing over it. Even though what they have done is thoroughly fascinating, I have to say that what emerges for me overall is a very mixed picture. I’ll try to explain…

Rohonc Codex codicology

Though at least half of the account of the history of research into the Rohonc Codex they present (pp.286-288) somewhat immodestly discusses their own findings and conclusions, Király and Tokai have clearly put a lot of effort into trying to understand the physical object itself (pp.288-293). Though a few of their codicological inferences are based on their interpretations of the pictures and text (and a number of their decryptions are inserted directly into the text as fact), most are based on exactly the kind of careful observation and physical insight you would hope to see.

Codicologically, what emerges more or less exactly mirrors what we see in the Voynich Manuscript:

* bifolios missing, swapped, and moved around arbitrarily, coupled with other sections that seem to have stayed intact.

* misleading foliation that was added long after bifolios had been shuffled

* misleading marginalia and notes added by owners who did not know what the text said

* some places where the picture was drawn first, others where the text was written first

* rebuttals of unjustified claims that there are no corrections

* rebuttals of unjustified claims that it must surely be a hoax

* and so forth.

As a result, I think that Király and Tokai’s codicological analyses imply that the Rohonc Codex has almost all the same physical and historical structures that the Voynich Manuscript has (niceties relating to textual analysis aside).

Cracking the Rohonc Codex’s numbers?

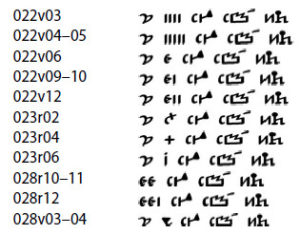

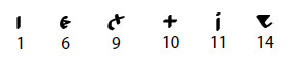

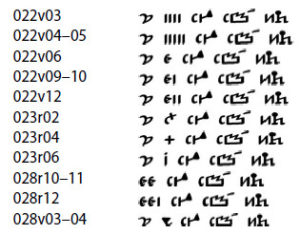

Király & Tokai point (pp.296-297) approvingly to Ottó Gyürk’s (1970) paper “Megfejthető-e a Rohonci-kódex?” [Can the Rohonc Codex Be Solved?]. Élet és Tudomány 25:1923–28, and extend the set of (what looks like) number instances that Gyürk found:

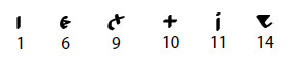

The underlying number pattern they infer from this sequence is as follows:

While their proposal that this is a number system that works like Roman numerals but where the ‘6’ has a shape instead of the ‘5’ (“V”) is possible, I have to say that to me it seems unbelievably unlikely (e.g. there’s nothing remotely like it in Flegg’s “Numbers Through the Ages”). It also seems likely to me that the text we see includes copying errors, and it may well therefore be that the specific sequence they highlight should have begun “III”, “IIII” (or probably the more idiosyncratically medieval “iij”, “iiij”) rather than “IIII”, “IIIII” as written. Instead postulating a 1-6-10 numbering system to explain this away seems too implausible to me.

What seems far more likely is that this is a kind of very slightly bastardized Roman numerals where you can write 5 both as “IIIII” and as “V”, in the same way that you can validly write 4 (additively) as “IIII” and (subtractively) as “IV”. Hence I’m currently far from convinced, based on what they have presented so far, that they have managed to nail down this basic part of the number system as well as they think they have.

They then proceed to construct an even more arcane number system which they assert encodes dates as if they were in Arabic numerals, but where the thousands digit and hundreds digit are reversed (i.e. what is written as “5160” actually means “1560”, where 1560 is a magic number “which is dated by old Christian tradition to the year 33 CE”):

When Gábor Tokai [discovered] the number 5166 next to the drawing of the three kings (21r) and 5199 (058r09 − 10) in the vicinity of drawings of the resurrection of Christ (56v, 59r), he affirmed that the numbers denote years.

OK, I can see how the logic arguing for this is so going to be so complex that it would need to be written up in a separate paper. But I can also see how I don’t believe what they have presented here at all: so I’m going to say that I’m sorry, but even though a good part of the underlying codicology and analysis is very likely highlighting some good stuff that needs working with and developing, I don’t believe the reconstructed number system claimed here is yet correct. 🙁

Cracking the Rohonc Codex’s code?

The paper tries to explain (p.293) what the authors have found (i.e. that ‘Rohoncese’ is a code, though one so complex that’s clearly not easy for them to explain why or how, which is why it is going to take several papers and several years of their effort) and what they are aspiring towards with their decryption efforts:

The principles of our criteria and method of codebreaking may seem banal to the reader, but we must emphasize them because of the bad reputation gained by the amateur researchers of the codex. Furthermore, as many examples in our next paper on the “wobbliness” of the code will show, the writing system is far from being simple and clean. We must affirm that these results are not due to methodically deficient research but to the writing itself, which was analyzed with painstaking care and strictness.

We demand that one symbol signify one thing, and whenever there is any digression from this principle — either by more symbols signifying one thing or one symbol signifying more things — it must be sufficiently supported by argument. Our case is difficult because the codex has codes signifying words of a language, and words behave less regularly than letters. In every natural language the presence of homonyms and synonyms creates ambiguity. Yet we demand that even this amount of ambivalence in our proposed solution be supported by evidence.

OK. So how does Király and Tokai’s actual decryption measure up to the lofty ideals they set for themselves here? Well… after a long series of caveats, concessions and defensive clauses, the whole section concludes (p.295):

Thus the plausibility of our proposed solution is difficult to specify. The core of our reading has such strong inner and outer evidence that we may affirm that it stands beyond doubt. The rest is of various degrees of certainty, which is indicated wherever necessary.

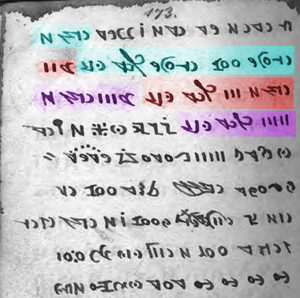

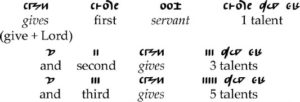

Their text then includes long readings of sections taken from the Rohonc Codex where tiny groups of letters are read as individual codes, which are in turn interpreted as individual words, all supporting each other. As a single line example, here’s the first part of the section that they believe is the Lord’s Prayer (p.303):

At the same time, the decryption never goes below the level of individual words. Are these pronounceable? What language are they derived from? How does this fit into the tree of European languages? These are all parceled off to be answered in future papers.

Probably the Best Part of the Paper

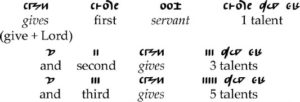

For me, the most persuasive-looking of all the authors’ codebreaking details relates to the Parable of the Talents:

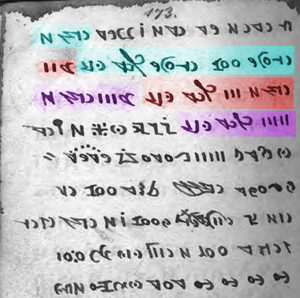

Here’s the same section in the Rohonc Codex (bearing in mind that the real text runs from right to left, whereas the transcription they present runs left to right), where I have highlighted the first line blue, the second line red, and the third line purple:

Despite having an O-Level in Religious Studies, I’d be the first to admit that my knowledge of the Bible is patchy. But even I knew that the above wasn’t quite how it was told in Matthew 25:14-30. Rather, the three servants got 5, 2, and 1 talents respectively, which is why they write up the “3” (actually 2) talents as [sic] on p.300:

14 For it will be like a man going on a journey, who called his servants and entrusted to them his property.

15 To one he gave five talents, to another two, to another one, to each according to his ability. Then he went away.

16 He who had received the five talents went at once and traded with them, and he made five talents more.

17 So also he who had the two talents made two talents more.

18 But he who had received the one talent went and dug in the ground and hid his master’s money.

Or, if you prefer, here’s the same section in the Latin Vulgate:

14 sicut enim homo proficiscens vocavit servos suos et tradidit illis bona sua

15 et uni dedit quinque talenta alii autem duo alii vero unum unicuique secundum propriam virtutem et profectus est statim

16 abiit autem qui quinque talenta acceperat et operatus est in eis et lucratus est alia quinque

17 similiter qui duo acceperat lucratus est alia duo

18 qui autem unum acceperat abiens fodit in terra et abscondit pecuniam domini sui

So: if their claimed block equivalence to the first half of Matthew 25:15 is indeed correct (and there are arguments both for and against this), perhaps the right question to be asking is whether there is there some odd Mitteleuropa tradition whereby the number of talents in this parable is not 5/2/1 but 1/3/5?

So, What Does Nick Think About All This?

In the best footballing tradition, Király and Tokai’s paper is (as the above should have made abundantly clear) a game of two very different halves.

By which I mean:

* the first 45 minutes stand as testament to the authors’ codicological hard work, almost all of which I’m convinced will stand as really strong, freestanding research (but which would have been further strengthened by unpicking various assertions that derive from their decryption). I would further include here the grounds from which they inferred the existence of a numbering system (though not the actual numbering system they describe itself)

* the second 45 minutes revolve around an attempt at a decryption that occasionally seems to work at a word level, but without ever getting to the bottom of what is actually going on (i.e. in terms of letters / grammar / structure etc).

The authors approvingly summarize (p.287) Benedek Láng’s view of the Rohonc Codex:

Láng’s greatest achievement was his attempt to identify the type of the cipher or code. He saw three options as equally possible: a monoalphabetic cipher with homophones, nullities, and nomenclators; stenography; or an artificial (“perfect”) language.

And yet, just as with the Voynich Manuscript, reducing the question of a writing system to precisely three mutually exclusive pigeonholes is an intellectually barren starting point, one which the astute Láng himself would surely be uncomfortable with. There are many more overlapping possibilities to consider, such as abbreviating shorthand (i.e. where words are contracted or truncated), alphabets based on pronunciation, and so forth.

Personally, I would be entirely unsurprised if the codicological analysis Király and Tokai carried out that led to their finding even half a line of a block equivalent (i.e. the the first half of Matthew 25:15) will turn out to be the first glimmer of a Rohonc “Rosetta Stone”: and for that all credit should be due to them. However, I don’t yet believe that the rest of their analysis has born the tasty fruit they think it has: and so there will likely be many more twists and turns for them to go through in their quest to decrypt the “Hungarian Voynich”.