Because last year’s Voynich research brought me a step closer to German calendars, I finally got round to reading Ernst Zinner’s epic “Regiomontanus: His Life and Works” (or, rather, to Ezra Brown’s 1990 translation of the same).

On the one hand, Zinner is crushingly magisterial, in both tone and deep attention to detail (though the appendices by other scholars do sometimes highlight Zinner’s occasional dependence on others’ unreliable translations). Yet on the other hand, it is a style of writing characterized by what is clearly a passionate drive to understand Regiomontanus within his cultural, scientific, and mathematical context.

Say what you like about Zinner, but you could never accuse him of skimming the surface of the subject: as the old joke goes, he’s definitely more bacon than eggs (i.e. where “the chicken is involved but the pig is committed”).

Peuerbach and nocturnals

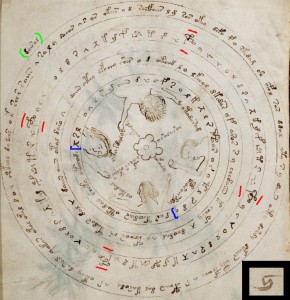

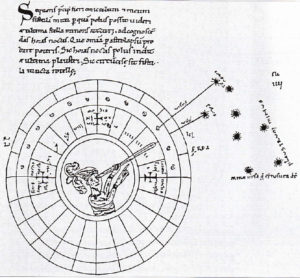

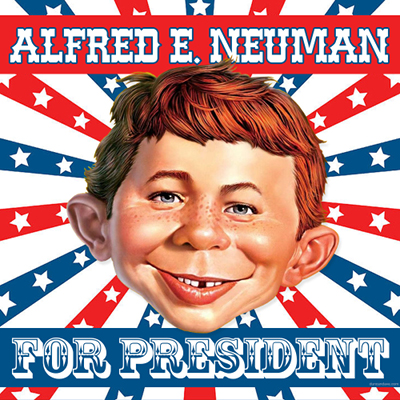

I’ve written a number of times before about how I strongly suspect that the circular drawing on f57v had a ring of letter groups that was originally made up of 4 x 18 symbols, but where the first two letter shapes of each set of eighteen were subsequently joined together into odd gallows-like characters to turn the sequence into a (far more mysterious) 4 x 17 letter-group sequence. Quite why the author did that is not known, but it would seem to me to have been done to conceal the extrinsic 4 x 18 structure.

Why, you may ask, would a 4 x 18 ring be a giveaway? This, in my opinion, is because 360 degrees / (4 x 18) = 5 degrees, which is the kind of explicit marking you would see on an astrolabe-like instrument of some sort. And because one of the secret astrolabe-like instruments of the mid-fifteenth century was the “nocturnal”, “nocturlabe” or “stardial” (astrolabes themselves were hardly secret by that time), I have long wondered whether what was depicted here was this specific instrument.

And so I was fascinated to read the following brief note in Zinner (pp.26-26), in his discussion of Georg Peuerbach (Regiomontanus’ mentor and teacher):

From 1455 on, there existed “stardials” [nocturnals] to tell time at night by means of the Pole Star and two stars {the “pointers”} in Ursa Major.

The footnote reference Zinner gives for this is: “Ernst von Bassermann-Jordan. Uhren. Berlin, 1922. Figure on page 21.” And so I went off (eventually) to have a look for this specific edition.

It turns out that von Bassermann-Jordan was a well-known clock and watch collector, whose classic book (“Uhren”) on the subject was reprinted many times. I was therefore delighted to find out that I could order a relatively cheap print-on-demand copy of the exact same 1922 version that Zinner referenced, and speedily sent off my money.

I must admit to having been a little bit surprised when a padded envelope appeared covered in Indian stamps (I must admit to having wondered whether it was a coincidence that “Uhren” was an anagram of “Nehru”), but that’s globalization for you.

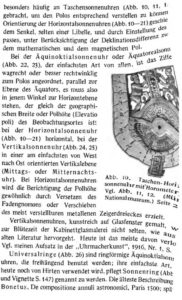

Even though the print-on-demand book cover was really quite nice, the quality of the scans inside was unfortunately more than a little disappointing in places. But even so, I could now try to find what von Bassermann-Jordan said on page 21 that Zinner remarked upon. Sadly, this was one of the many places where the scans became somewhat unrecognizable by the right-hand edge.

Yet because I was able to use Google to search for “Orientierung der Horizontalsonnenuhren” on the same page, this yielded three hits on archive.org, including the 1922 edition I had just bought. (There was also a 1914 edition and a 1920 edition). Unsurprisingly, the 1922 edition was (without any real doubt) the source of the somewhat mangled scans for the Indian POD company, so I can show you what I was trying to read, direct from the source:

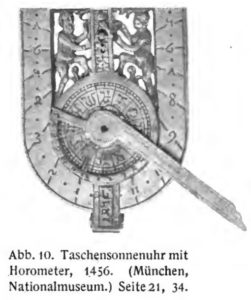

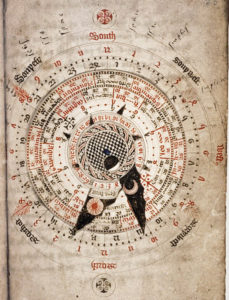

Even so, this meant that I was able to find the same thing in the (much clearer, and significantly more readable) 1920 edition of “Uhren”, so that you can hopefully see the structure of the nocturnal (dated “1456”) much more clearly:

I presume that this is referring to the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich, which (encouragingly) has a collection of scientific instruments. However, I wasn’t able to find the one depicted in its object database (and I suspect Zinner wasn’t able to find it either), but perhaps one of my German readers will have more luck than me. 🙂

Other nocturnals

A very good source for the history of the nocturnal is Günther Oestmann’s (2001) “On The History of the Nocturnal“. Oestmann notes that the idea that the nocturnal was first invented in China has been comprehensively debunked, and that it is instead a European invention – there are no Arabic nocturnals from the Middle Ages. There was also a predecessor to the nocturnal (a sighting tube and disk, described by Pacificus in the 10th century), but the more compact hand-held nocturnal was clearly a far more usable version of the same thing.

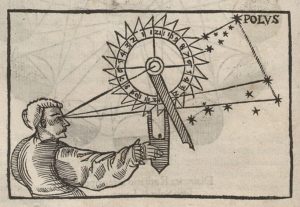

The “V2.0” idea of nocturnals had actually been discussed as early as the 12th century (though few seem to have been actually built). Raymon Lull mentions the nocturnal in his Nova geometria (1299), and the device was made famous by Peter Apian’s 16th century printed book:

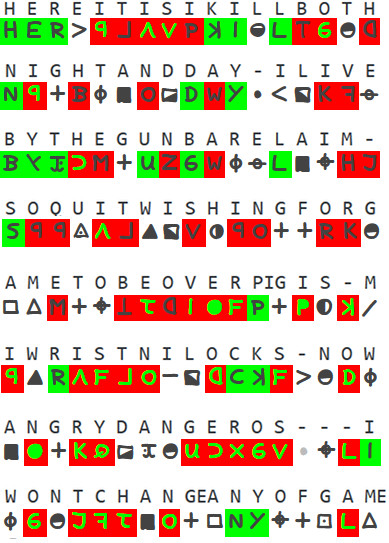

But documentation on nocturnals between Lull and the 1456 nocturnal noted by von Bassermann-Jordan and Zinner seems quite thin. Oestmann lists all the 15th century nocturnal manuscripts he is aware of, together with references (not included here) to where they are mentioned in Zinner’s (1925) “Verzeichnis der astronomischen Handschriften des deutschen Kulturgebietes“:

* Wolfenbüttel, HAB: Cod. Guelf. 81.26 Aug. 2°, fol. 144v (Use of the Nocturnal, Latin 1461)

* Göttingen, UB: 2° Philos. 42m, fol. 55r/v .00 (Johann v. Gmunden [?], Construction of the Nocturnal, in a collection of astronomical texts, 15th cent.)

* Würzburg, UB: M. ch. q. 132, fol. 153v-154v, 155v (Construction of the Nocturnal, Latin, in a collection of astronomical texts, late 15th cent.)

* Leipzig, UB: Cod. 1469, fol. 201r-207r (Construction of the Nocturnal, Latin, in a collection of astronomical texis, 14-15th cent.)

* Munich, Bayer. StB: Clm 24105, fol.65v-67r (Use of the Nocturnal, German, in a collection of astronomical texts, 15/16th cent.)

* Munich, Bayer. StB: Clm 214, fol. 167r-185v (Construction of the Nocturnal, Latin, in a collection of astronomical tables, 15th cent.)

* Bern, Burgerbibl.: Cod. 157 fol. 27v-28v (Construction and Use of the Nocturnal, Latin, 15th cent.)

* Zürich, Zentralbibl.: Ms. C 107, fol. 107r/v (Wilhelm Hofer, Carthusian monk and pupil of Georg Peuerbach), Construction and Use of the Nocturnal, Latin, Gaming (Lower Austria) 1472/79); see L. C. Mohlberg, Mittelalterliche Handschriften (= Katalog der Zentralbibliothek Zürich, vol. I), Zürich 1951, p.55f., 361).

* Ottobeuren, Klosterbibl.: Ms. II, 319, fol. 122-123 (Construction of the Nocturnal, 15th cent.)

* Meiningen, Landesbibl.: Pd 32.44, fol. 92r-98v, 104r-105v (Construction of the Nocturnal, 15th cent.)

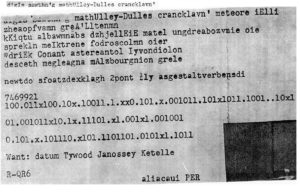

Oestmann also mentions Chartres MS 214 (olim 173; destroyed in 1944), which looked like this, though note that it actually belongs to the earlier “sighting tube” tradition from Pacificus:

But because Oestmann relies on Zinner, who in turn was only looking at astronomical manuscripts within the German cultural orbit, there are doubtless many more to be found. For example, there’s a nice volvelle nocturnal in fol. 25r of MS Ashmole 370, an English manuscript dated ~1424 that I’d really like to see the rest of one day:

If anyone is aware of a better / more recent / more pan-European source on the 12th-15th century history of the nocturnal / nocturlabe than Oestmann, please let me know!

“Stretched out arms”

For Voynich researchers, I would argue that the single most extraordinarily interesting paragraph in Oestmann’s paper is as follows:

Closely connected with the history of the nocturnal are certain diagrams in nautical texts, which served as mnemonic devices for the correction of the measured altitude of the Pole Star. The position of α and β Ursae minoris respectively α and β Ursae maioris, often called ‘Guards’, indicated the correction to reduce the observed Pole Star altitude to obtain latitude. A man with stretched out arms standing in the Pole was used. If the Guards were found over his head the Pole Star stood 3°5′ under the Celestial Pole and vice versa. The two arms marked the side deviations and also intermediate positions were recorded in mnemonic verses.

Given that f57v specifically depicts people with stretched out arms (at the top and the bottom), I suspect that this is an avenue of research that is well worth pursuing further:

Oestmann’s footnote #17 gives as his source:

See for example the Regimento do Norte (probably composed in the 15th century; München, Bayer, StB: 4° Inc., 1551). On the nautical ‘Regiments’ see Joaquim Bensaude, L’astronomie nautique au Portugal à l’époque des grandes de couvertes (Bern, 1912/17, repr. Amterdam 1967), pp. 136-145, 223f.; Hermann Wagner ‘Die Entwicklung der wissenschaftlichen Nautik im Beginn des Zeitalters der Entdeckungen nach neuern Anschauungen’, Annalen der Hydrographie und Maritimen Meteorologie, 46 (1918), pp. 215-220.