I’m cautiously optimistic that a breakthrough has just emerged to do with the Art History origins of the Voynich Manuscript’s puzzling zodiac pages, that would appear to connect them with Diebold Lauber’s fifteenth century manuscript copying house. Errrm… who he? I’ll explain…

The Voynich Zodiac section

Even though we cannot decrypt the Voynich Manuscript’s text, researchers have long noted that its illustrations strongly suggest that the manuscript isn’t just random, but is instead composed of a number of thematically-connected sections.

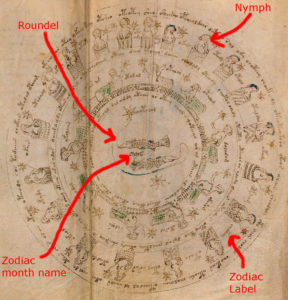

The Voynich zodiac section contains a series of roundels depicting the signs of the zodiac (though the folio at the end containing Capricorn and Aquarius has without any real doubt been removed). Each roundel is surrounded by 15 or 30 small naked women (‘zodiac nymphs’, though Pisces has only 29) posed somewhat awkwardly, each of whom is linked to a small fragment of text (‘zodiac labels’). Here’s Pisces:

[Note that one early owner seems to have added month names to its roundels (e.g. March to Pisces, April to Aries, etc) in a somewhat rough and ready hand, but that’s another matter entirely.]

I’ve argued for years (and the idea certainly wasn’t mine) that the central drawings were probably loosely copied from an astronomical calendar or hausbuch, of the type entirely typical of late 14th or early 15th century Germany, a good number of which had strikingly similar circular astrological or astronomical roundels.

But despite Voynich researchers’ Herculean efforts in recent years to cross-reference these medical/astronomical hausbuch drawings to the Voynich’s zodiac drawings, results have been mixed at best: a zodiac sequence with a good Pisces or Sagittarius match would for the other zodiac signs typically be accompanied by drawings that shared practically no similarities with the Voynich’s roundels. And so things, after a huge burst of collective enthusiasm a couple of years back, stalled somewhat.

Enter Koen Gheuens

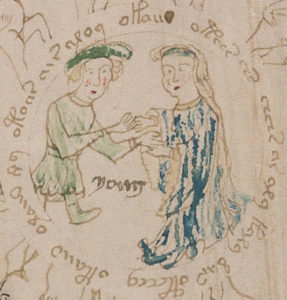

In 2016, researcher Koen Gheuens was looking at the Voynich zodiac Gemini roundel drawing, and wondered what the curious double-handed handshake gesture depicted there might signify or mean.

After the usual long sequence of dead-ends, he discovered that in fact it was a pose used in some medieval weddings, and that it even had its own literature. He describes it as follows:

The type of medieval marriage we’re interested in is as follows: the man and woman hold one hand (in cross, so left to left or right to right) and with his free hand, the man puts a ring on a finger of the woman’s free hand. This results in the “double handshake” look. The “passive” set of hands is usually pictured below, while the putting on of the ring is above.

Koen found a number of depictions of the double-handed marriage – very ably documented on his Voynich Temple website – which progressively led him to the manuscript workshop of Diebold Lauber.

Diebold Lauber

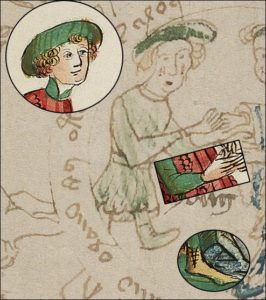

In the days before printing, manuscript workshops had to find ways of churning out work for clients that was cost-effective: drawings in particular were time-consuming. The particular ‘hack’ Diebold Lauber’s workshop seems to have made most use of was to have a set of pre-drawn generic exemplar poses which were then lightly adapted (presumably by less skilled illustrators) multiple times. In this way, drawings were reused and recycled multiple times: the connections between these recycled drawings gives plenty of grist for Art Historians’ mills to grind.

Koen put forward the idea that there seems to be a connection between a particular Diebold Lauber crossed-hands-marriage drawing dated to 1448 and the Voynich zodiac crossed-hands Gemini roundel:

And once you see how the details parallel each other, it is indeed a very persuasive visual argument (Koen’s composite image):

Putting all the pieces of the historical puzzle together, it would therefore seem a perfectly reasonable inference that the Voynich zodiac roundel drawings were roughly copied from a zodiac sequence that appeared in an medical-astronomical hausbuch commissioned from Diebold Lauber’s manuscript workshop, where the Gemini pose had been recycled from an earlier Diebold Lauber crossed-hands marriage stock drawing exemplar.

Diebold Lauber References

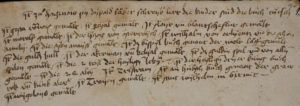

For a German-language description of Lauber’s prolific workshop in Hagenau (just North of Strasbourg), the Ruprecht-Karls University of Heidelberg has put together a nice page here. From this we learn that researchers have collected together about 80 examples of the workshop’s output dating from 1427 to 1467 (lists here): and that the illustrators worked as long-standing teams, with the so-called “Gruppe A” active from about 1425 to 1450. Lauber was effectively a bookseller, and even included a handwritten advertisement in some of his manuscripts, such as this one (from Cod. Pal. germ. 314, fol. 4ar) from 1443-1449:

A transcription and translation of this would be much appreciated! 🙂

A Diebold Lauber Calendar

What might a Diebold Lauber medical/astronomical calendar look like? Luckily, we don’t need to wonder: there was one in the library of Colonel David McCandless McKell in Lexington, Kentucky, that Rosy Schilling wrote two short books about (one a facsimile of the MS, the other a transcription and English translation).

* Rosy Schilling: A facsimile of an Astronomical medical calendar in German (Studio of Diebolt Lauber at Hagenau, about 1430 – 1450): from the Library of Colonel David McC. McKell, Lexington, Ky., 1958

* Rosy Schilling: Astronomical medical calendar: German, studio of Diebolt Lauber at Hagenau, 15th century, c. 1430 – 50, Lexington, 1958

Here’s what January looks like (i.e. Aquarius):

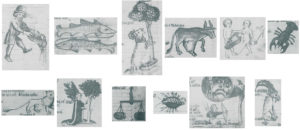

And – because I know you’re going to ask – here are all twelve zodiac signs from the McKell Ms (click for a larger version):

McKell’s extensive library was bequeathed to the Ross County Historical Society, though according to the Handschriftcensus entry, it was sold by Bloomsbury Auctions (8th July 2015, Sale No. 36180) to Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books AG. So anyone suitably rich who wants to own this can very probably do so. Which is nice.

So… What Next?

Personally, I’m not convinced every extant Diebold Lauber workshop drawing has been collected together yet. For example, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 1370 has been mentioned before by Voynich researchers on one of Stephen Bax’s pages (it was written in Strasbourg in the mid-15th century, certainly before 1467): and I would be unsurprised if it was connected with Lauber. Here is its Sagittarius roundel:

I’m also far from convinced – given that medical/astronomical hausbuchen don’t have a huge literature – that there aren’t other Diebold Lauber calendars out there that haven’t yet been recognized for what they are. Perhaps this should be a good direction to pursue next? Something to consider, anyway.