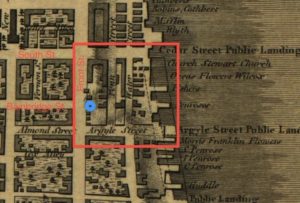

Before revealing the precise modern equivalent of the location near Cherry Garden where the Society Hill treasure was allegedly buried 😉 , I think we need to take a brief detour into the world of Philadelphia’s pirate treasure lore.

Our guide is the ever-detailed (and not infrequently skeptical) (1830) “Annals of Philadelphia, being a collection of memoirs, anecdotes, and incidents of the city and its inhabitants, from the days of the Pilgrim founders” compiled by John Fanning Watson. For all its flaws, Watson’s book is surely the first (wary) port of call for anyone sailing the murky depths of Philly’s early history: and remains a comfortable lapdog of a read (though the reader’s eye inevitably tires after each few chapters).

In short, think of Watson’s Annals as a Philly equivalent of Captain Charles Johnson’s “A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates”, and you shouldn’t go too far wrong. 🙂

Captain Kidd

Watson, having done much research on the subject, seems in no doubt of Captain Kidd’s connection to Philadelphia, or at least to Kidd’s crew:

A writer at Albany, in modern times, says they had the tradition that [Captain] Kid once visited Coeymans and Albany; and at a place two miles from the latter it was said he deposited money and treasure in the earth. […]

In 1699, Isaac Norris, sen. writes, saying, “We have four men in prison, taken up as pirates, supposed to be Kid’s men. Shelly, of New York, has brought to these parts some scores of them, and there is sharp looking out to take them. We have various reports of their riches, and money hid between this and the capes. There was landed about twenty men, as we understand, at each cape, and several are gone to York. A sloop has been seen cruising off the capes for a considerable time, but has not meddled with any vessel as yet, though she has spoken with several.”

The above quoted letter, in the Logan MS. collection, goes to countenance the prevalent idea of hidden money. The time concurs with the period Captain Kid was known to have returned to the West Indies. It may have been the very sloop in which Kid himself was seeking means of conveying home his treasure, and with which he finally went into Long Island sound to endeavour to make his peace. Four of the men landed at Lewistown, were apprehended and taken to Philadelphia; I saw the bill of their expense,” but heard no more of them, save that I saw that Colonel Quarry, at Philadelphia, was reproached by William Penn for permitting the bailing of the pirates; some were also bailed at Burlington. — Vide Penn’s letter of 1701.

Blackbeard

Watson is even more taken with the much-claimed connection between Blackbeard and Philadelphia:

Mrs. Bulah Coates, (once Jacquet,) the grandmother of Samuel Coates, Esq. now an aged citizen, told him that she had seen and sold goods to the celebrated Blackbeard, she then keeping a store in High street, No. 77, where Beninghove now owns and dwells a little west of Second street. He bought freely and paid well. She then knew it was him, and so did some others. But they were afraid to arrest him lest his crew, when they should hear of it, should avenge his cause, by some midnight assault. He was too politick to bring his vessel or crew within immediate reach; and at the same time was careful to give no direct offence in any of the settlements where they wished to be regarded as visiters and purchasers, &c.

This of course gives me an excuse to put in the famous picture of Blackbeard that everyone loves so much:

Watson adds:

There is a traditionary story, that Blackbeard and his crew used to visit and revel at Marcushook, at the house of a Swedish woman, whom he was accustomed to call Marcus, as an abbreviation of Margaret.

(Incidentally, there’s a 1735 plank-built house in Marcus Hook that the owners like to try to associate with Blackbeard and his friend Margaret, just so you know.)

All of which helps to support stories telling of buried pirate treasure in Philadelphia, though the spookier the better (obviously):

An idea was once very prevalent, especially near to the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers, that the pirates of Black Beard’s day had deposited treasure in the earth. The conceit was, that sometimes they killed a prisoner, and interred him with it, to make his ghost keep his vigils there as a guard “walking his weary round.”

Treasure Hunter Tales

Watson counted treasure hunters among his friends, though again with a spooky edge:

Several persons, whose names I suppress, used to go and dig for hidden treasures of nights. On such occasions if any one “spoke” while digging, or ran from terror without “the magic ring,” previously made with incantation round the place, the whole influence of the spell was lost.

And treasure hunters back then were apparently just about as gullible as their modern versions:

There was a prevailing belief that the pirates had hidden many sums of money and much of treasure about the banks of the Delaware. Forrest got an old parchment, on which he wrote the dying testimony of one John Hendricks, executed at Tyburn for piracy, in which he stated that he had deposited a chest and a pot of money at Cooper’s Point in the Jerseys. This parchment he smoked, and gave to it the appearance of antiquity; calling on his German taylor, told him he had found it among his father’s papers, who got it in England from the prisoner whom he visited in prison. This he showed to the taylor as a precious paper which he could by no means lend out of his hands. This operated the desired effect.

Soon after the taylor called on Forrest with one Ambruster, a printer, who he introduced as capable of “printing any spirit out of hell,” by his knowledge of the black art. He asked to show him the parchment; he was delighted with it, and confidently said he could conjure Hendricks to give up the money. A time was appointed to meet in an upper room of a public house in Philadelphia, by night, and the inn-keeper was let into the secret by Forrest. By the night appointed, they had prepared by a closet a communication with a room above their sitting room, so as to lower down by a pulley the invoked ghost, who was represented by a young man entirely sewed up in a close white dress on which were painted black eyed-sockets, mouth, and bare ribs with dashes of black between them, the outside and inside of the legs and thighs blacked, so as to make white bones conspicuous there. About twelve persons met in all, seated around a table. Ambruster shuffled and read out cards, on which were inscribed the names of the New Testament saints, telling them he should bring Hendricks to encompass the table, visible or invisible he could not tell. At the words John Hendricks “duverfluchter cum heraus,” the pulley was heard to reel, the closet door to fly open, and John Hendricks with gastly appearance to stand forth. The whole were dismayed and fled, save Forrest the brave. After this, Ambruster, on whom they all depended, declared that he had by spells got permission to take up the money. A day was therefore appointed to visit the Jersey shore and to dig there by night. The parchment said it lay between two great stones. Forrest, therefore, prepared two black men to be entirely naked except white petticoat-breeches; and these were to jump each on the stone whenever they came to the pot, which had been previously put there. These frightened of the company for a little. When they next essayed they were assailed by cats tied two and two, to whose tails were spiral papers of gunpowder, which illuminated and whizzed, while the cats whawled. The pot was at length got up, and brought in great triumph to Philadelphia wharf; but oh, sad disaster! while helping it out of the boat. Forrest, who managed it, and was handing it up to the taylor, trod upon the gunnel and filled the boat, and holding on to the pot dragged the taylor into the river — it was lost!

For years afterwards they reproached Forrest for that loss, and declared he had got the chest by himself and was enriched thereby. He favoured the conceit, until at last they actually sued him on a writ of treasure trove; but their lawyer was persuaded to give it up as idle.

And other pirate treasure hunter stories float in the Philly ether:

As late as the year 1792, the shipcarpenters formed a party to dig for pirates’ money on the Cohocksinc creek, northwest of the causeway, under a large tree. £ frightened off. And it came out afterwards that a waggish neighbour had enacted diabulus to their discomfiture.

Pirate Treasure

Some claim to have found Blackbeard’s pirate treasure in Philadelphia, but without anything to support them:

Colonel A. J. Morris, now in his 90th year, has told me that in his early days very much was said of Blackbeard and the pirates, both by young and old. Tales were frequently current that this and that person had heard of some of his disgovered treasure. Persons in the city were named as having profitted by his depredations. But he thought those things were not true.

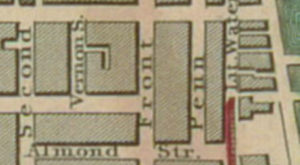

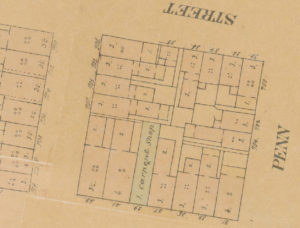

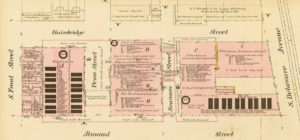

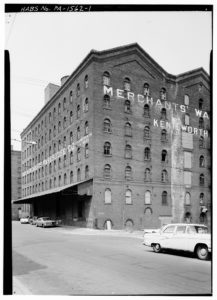

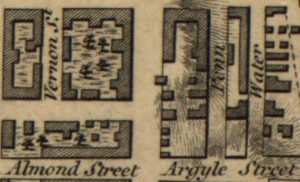

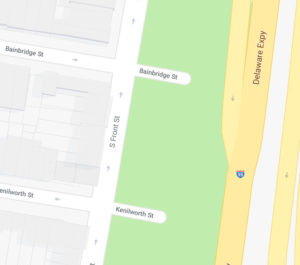

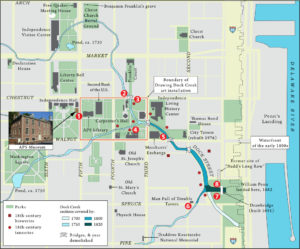

South Front Street, not far from the Delaware (“as you are well aware”), was specifically named as a place where treasure was dug up:

T. Matlack, Esq. told me he was once shown an oak tree, at the south end of Front street, which was marked KLP, at the foot of which was found a large sum of money. The stone which covered the treasure he saw at the door of the alleged finder, who said his ancestor was directed to it by a sailor in the Hospital in England. He told me too, that when his grandfather Burr died they opened a chest which had been left by four sailors “for a day or two,” full twenty years before, which was found full of decayed silk goods.

(As an aside, Cipher Mysteries readers may perhaps remember the meta-story of treasure locations being divulged by dying sailors which Ron Justron’s “Great Lost Treasure” claims revolved around: here’s an early-ish example.)

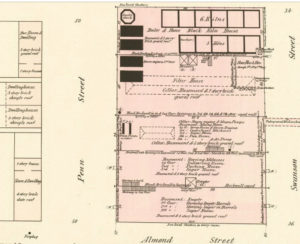

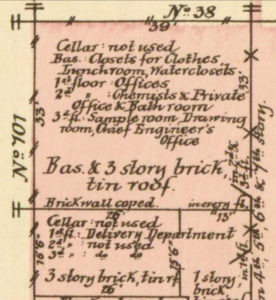

Philadelphia pirate treasure, previously hidden underground, tended to turn up when people dug cellars, such as at the Cock inn in Spruce Street:

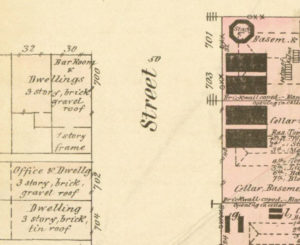

Samuel Richards and B. Graves confirmed to me what I had heard elsewhere, that at the sign of the Cock in Spruce street, about 35 years ago, there was found in a pot in the cellar a sum of money of about 5000 dollars. The Cock inn was an old two story frame house which stood on the site of the present easternmost house of B. Graves’ row. A Mrs. Green owned and lived in the Cock inn 40 to 50 years ago, and had sold it to Pegan, who found the money in attempting to deepen the cellar. It became a question to whom the money belonged, which it seems was readily settled between Mrs. Green and Pegan, on the pretext that Mrs. Green’s husband had put it there! But it must appear sufficiently improbable that Mrs. Green should have left such a treasure on the premises if she really knew of it when she sold the house. The greater probability is that neither of them had any conception how it got there, and they mutually agreed to support the story, so as to hush any other or more imposing inquiries. They admitted they found 5000 dollars. It is quite as probable a story that the pirates had deposited it there before the location of the city.” It was of course on the margin of the natural harbour once formed there for vessels. In digging the cellar of the old house at the north east corner of Second street and Gray’s alley they discovered a pot of money there; also some lately at Frankford creek.

Certainly it was once much the expectation and the talk of the times — for instance, the very old two-story house at the north east corner of Second street and Gray’s alley, (i.e. Morris’ alley) originally built for Stephen Anthony, in digging its cellar they found there a pot of money, supposed to have been buried by the pirates. This story I heard from several very aged persons.

Treasure Maps

Finally, Watson sees no reason why there should not also be treasure maps or “hints”, and sees the idea as “natural”, though it does not sound as though he himself has seen one (for he would surely have gleefully included it in his Annals):

When we thus consider “their friends” thus “lodged among us every where,” it presents additional reasons for the ideas of buried treasure of the pirates once so very prevalent among the people, of which I have presented several facts of digging for it under the head of Superstitions. They believing that Blackbeard and his accomplices buried money and plate in numerous obscure places near the rivers; and sometimes, if the value was great, they killed a prisoner near it, so that his ghost might keep his vigils there and terrify those who might approach. Those immediately connected with pirates might keep their own secrets, but as they might have children and connections about, it might be expected to become the talk of their posterity in future years that their fathers had certain concealed means of extravagant living; they may have heard them talk mysteriously among their accomplices of going to retired places for concealed things, &c. In short, if given men had participation in the piracies, it was but natural that their proper posterity should get some hints, under reserved and mysterious circumstances of hidden treasure, if it existed.