For more than forty years, the late historian Gustina Scaglia researched 15th and 16th manuscripts containing drawings of machines. This led to her writing (some with Frank D. Prager) a number of highly regarded books, a good number of which I can afford (and have copies of) and a fair few my budget cannot easily stretch to. :-/ The list of her machine-related papers stretches back at least to her 1960 NYU thesis Studies in the “Zibaldone” of Buonaccorso Ghiberti (Advisor: Richard Krautheimer).

Overall, I think what emerged can be fairly described as a decades-long research programme to work out how these technical books and drawings fitted together into an larger inventive tradition – i.e. to determine where machine ideas really came from, and how they flowed from manuscript to manuscript, being adapted and adjusted as they went.

In many ways, Scaglia achieved just about everything she aimed to do: her accounts of Brunelleschi, Mariano Taccola, and Francesco di Giorgio’s books (and all their copybooks and derivative works, sprawling through the 16th century and beyond) in many ways exemplify the best of historical scholarship – despite covering such a large area, they are well researched, well thought through, and lucidly presented. And yet…

The Hole At The Centre: The Machine Complex Authors

It’s hard not to notice that there is a hole at the centre of Scaglia’s account, one which never seems to have been resolved (at least, not in those papers and books of hers that I’ve read). Although a very large number of machine drawings in Francesco di Giorgio’s books were derived directly from Mariano Taccola, Francesco di Giorgio also had a second major source for his machine drawings, a source which Scaglia was able to track only indirectly: she called these sources “the Machine Complex Authors“.

(Note that her 15th century Machine Complex Author(s) are different from the quite separate 16th century person she calls The “Machine Complex Artist”, who she concludes was active in Siena, and whose works Oreste Vannucci Biringucci copied into his books of drawings. I thought I’d mention this as it’s easy to get confused by these two similar names.)

Scaglia talks a little about the Machine Complex authors in her “Francesco di Giorgio: Checklist and History of Manuscripts and Drawings in Autographs and Copies from ca. 1470 to 1687 and Renewed Copies (1764-1839)”, in an early section devoted to Francesco di Giorgio’s Opusculum de Architectura (British Museum 197.b.21, formerly MS Harley 3281):

Francesco’s other engine designs in the Opusculum, which may be briefly designated as the Machine Complexes, and fort plans had all been composed by anonymous artisans in 1450-1470 or earlier, none of which appear in Taccola’s sets […] These Machine Complex designs, largely formed in the artisans’ imaginations, are often inoperable, greatly constricted by the box frame in which the components are fitted […] [p.43]

Essentially, by the time sixteenth century engineers began to look with a more experienced eye at these 15th century drawings, it was clear that they were almost all impractical (and indeed occasionally fantastical): that if they were to be built, they would inevitably “move slowly”, as the architect Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane put it.

To the best of my knowledge, if Scaglia ever had an inkling of who might have been the “anonymous artisans” who conjured up those additional Machine Complex drawings that Francesco di Giorgio used, she never wrote it down. This was the hole in her history she never managed to fill: Scaglia’s unfinished business, as it were.

Was Filarete a Machine Complex Author?

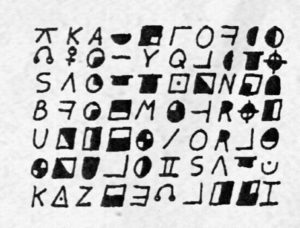

In “The Curse of the Voynich” (2006), I explored the idea that the Voynich Manuscript might have been (in some way) a version of the little books of secrets mentioned many times by architect Antonio Averlino, scattered through his libro architettonico. According to Averlino, they contained secrets related to agriculture, water, machines, bees and so forth (though he never actually included a formal list).

Opinions are sharply divided about these little books, allegedly composed during Averlino’s time as ducal architect in Milan (1450-1465): some historians think they never existed at all (i.e. that they were just a literary conceit in Averlino’s part-factual / part-fictional libro architettonico), while others think that they did exist and that trying to make money out of them was one of the reasons Averlino wrote his libro at all. Either way, there is currently no known evidence outside the four walls of the libro architettonico that supports or refutes either account: so all we really have to go on is what Averlino tells us.

However, since 2006, I have further speculated that Averlino might have been the author of some of the Machine Complex drawings. This is historically compatible based on what we know of both: the period when Averlino claimed to have written / invented / compiled his book of machine secrets was within exactly the same period Scaglia concluded the Machine Complex Authors were active in Italy, after Taccola’s works (-1449) and before Francesco di Giorgio’s early works (1470-1475). And Averlino’s death (probably in Rome sometime between 1465 and 1469) would be about the right time for some or all of his books of secrets to make their way out into the world.

Did Scaglia consider the possibility that Averlino may have been one of the mid-Quattrocento Machine Complex Authors? Scaglia did, in 1974, write a glowing review in Isis of Finoli and Grassi’s scholarly edition of Antonio Averlino’s libro architettonico (a review I’ve only read the first page of, sadly), so would have been well aware that Filarete had claimed authorshop of a book of machines, something that fell squarely within her long-term research programme. But perhaps the lack of corroborating external evidence for this meant that positing a link to the Machine Complex Authors would perhaps have been more openly speculative than she was comfortable with: perhaps someone more familiar with her work than me will be able to say.

Machines Hidden In Plain Sight?

If, for the sake of argument, we temporarily accept the premise that Averlino’s book of machine secrets did end up concealed in the Voynich Manuscript, the obvious question is: where are they? When I was researching Curse, it was very easy to see how a book on “agriculture” could be behind the Voynich Manuscript’s herbal pages, and also to see how a book on “water” could be behind the Voynich Manuscript’s ‘balneological’ quire (with its drawings of baths, and even possibly a rainbow at the end): so the absence of machine drawings was an issue that vexed me a great deal.

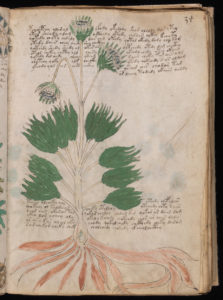

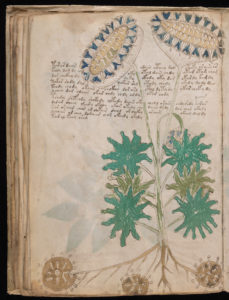

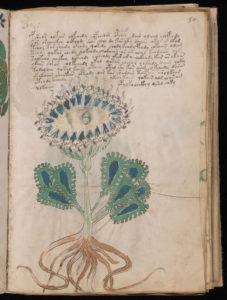

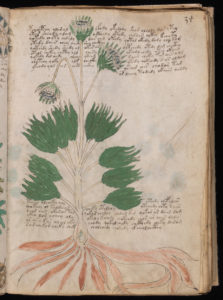

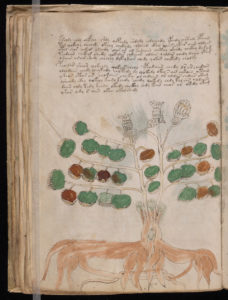

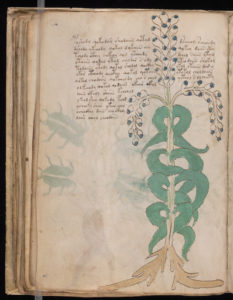

Though still just as hypothetical as it was more than a decade ago, the prediction this led me to remains controversial, simply because it is both simple and outrageous: that if Averlino’s book on machines (and it would inevitably be, like Taccola’s drawings that went before it, very visually oriented) is somehow hidden in the Voynich Manuscript’s pages, I concluded that the only place it could be hidden in plain sight was in the Voynich Manuscript’s “Herbal B” pages.

The text on (what Prescott Currier famously called) Herbal A pages was written by a larger, more open hand than the scratchy, smaller hand that wrote Herbal B pages: and despite superficial similarities, the two sets of pages have significantly different statistical profiles. Even though Herbal A bifolios have ended up (partially) mixed in with Herbal B bifolios, there seems little doubt that the two were originally composed in separate writing phases, and perhaps even written by different scribes.

Hence: even though both groups of pages are made up of plant drawings (normally one per page) accompanied by blocks of text (sometimes interleaved through the drawings), there seems very strong grounds for concluding that the two groups could well be quite different at heart. One of the things that distinguished Curse was that it proposed that these two groups of pages might well contain two different books – a book on agriculture, and a book of machines.

“Sunflowers” or Gears?

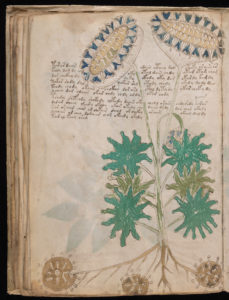

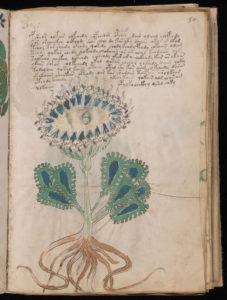

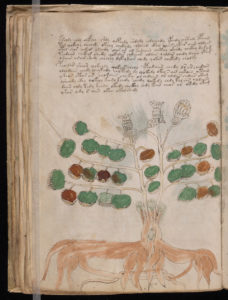

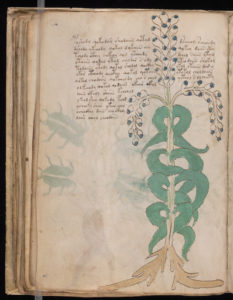

Since writing Curse, I’ve read a lot more of the 15th century machine drawing literature than I was able to before. And even now (in 2018), the systematic set of visual parallels I draw in 2006 seem no less strong: I still don’t see Brumbaugh’s supposed “sunflowers”, but wind-powered mills (and even wind-powered cars, something that had already been invented – though not built – by the early 15th century)

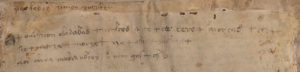

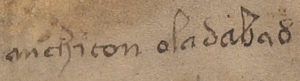

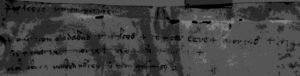

I also don’t see implausible plants, but rather obfuscated details that I suspect represent the racks and pinions that appear in 15th century machine drawings:

Additionally, I see what appear to be concealed versions of the horse-powered (or ox-powered) hoists that were such a mainstay of the 15th century machine drawing tradition (i.e. in Buonaccorso Ghiberti, Taccola, and elsewhere):

Finally: given Filarete’s love of fountains, it’s also easy (once you get to this point in the whole train of thought) to wonder whether some Herbal B Pages depict fountains:

As always, your mileage may vary: make of it all what you will.

Weak vs Strong Research Questions

The research brick wall I ran into with Curse was that Averlino’s books of secrets are – as far as anyone can say – entirely internal to his libro architettonico, making them virtual, unproven, implicit, or even absent: no-one can tell. And as for whether Gustina Scaglia ever considered (or even pursued) the idea of Averlino as a possible Machine Complex Author, she passed away 15 years ago, so that’s not really an avenue that can be followed.

However: what struck me in the last few days is that even though individually both are weak (i.e. untestable) research questions, if you put the two together you get a strong research question – by which I mean a question that can be tested against actual evidence, and perhaps falsified or proved. The point is that whatever trying to answer the question reveals, it should be possible to use the result to learn something new.

That is, even though the following claims have proven almost impossible to individually test (i.e. they are weak research questions)…

* that Averlino wrote the Voynich Manuscript

* that Averlino wrote books of secrets including a book of machines

* that the Voynich Manuscript’s Herbal B pages contain encrypted or obfuscated versions of his machine drawings

* that Averlino was one of Scaglia’s Machine Complex Authors whose drawings were copied by Francesco di Giorgio in 1470-1475

…if you put all of them together into a single composite claim…

* that Averlino’s drawings appear both in the Voynich Manuscript’s Herbal B pages and in Francesco di Giorgio’s machine drawings

…you get a strong research question, i.e. something that can actually be tested. So my next step is obviously going to be working out precisely which of Francesco di Giorgio’s drawings came not from Mariano Taccola but from the Machine Complex authors, and then comparing those with the Voynich’s Herbal B page drawings to see if anything connects the two.

However, apart from some references by the British Museum’s curators to figures in an unnamed book by someone called “Mancini” (presumably Girolamo Mancini?), I don’t know if there is a facsimile reproduction of the Opusculum de Architectura – if anyone happens to know a facsimile of the Opusculum or what the name of Mancini’s book is, please let me know, thanks!

More generally, what I find interesting here is that for many years I have spent a lot of time trying to break down big research questions into smaller questions that can be researched and tested atomically. Yet here I’m having to work in quite the opposite direction, simply because the individual smaller research questions are each too weak to be answered. And that makes me wonder whether we as historical researchers are sometimes hamstrung for lack of larger vision: that we can spend too much time on tiny questions that we can only partially answer, when we should (at least some of the time) also try to construct larger, more daring problematiques (as the Annales historians liked to put it), which would be testable in quite different (and perhaps far more revealing) ways. Just something to think about, anyway.