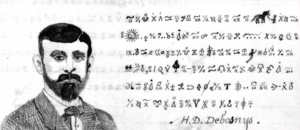

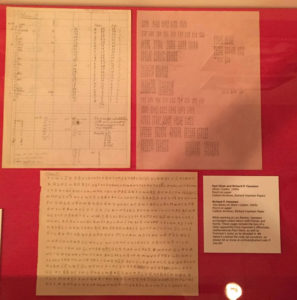

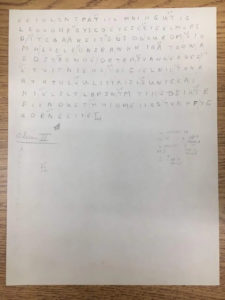

A trawl through newspapers.com’s (paywalled) archive throws up various tidbits to do with fantasy-spinning wife-killer Henry Debosnys. For example, that his defence counsel consisted of Arod K. Dudley of Elizabethtown and Royal Corbin of Plattsburgh; that his brain “weighed fifty-two ounces“; and that on the day of his execution, “he commenced the day with his usual series of noises in imitation of different animals, of which he was a perfect mimic”.

On that same day, he was asked by the Reverend Father Reddington if there was anything he wanted to say. Debosnys’ reply: “I have, I am innocent of the crime. You have made a mistake. The blood on my knife was the blood of a chipmunk.” Just so we have his – completely credible – story of how he didn’t kill his wife on record. Lying bastard.

“Paris green and vinegar”

Perhaps more intriguingly, a short piece in the Citizen-Examiner of Hayneville, Alabama (15th Nov 1882) shows a further side to Debosnys:

He wrote an ordinary letter and handed it, open, to the sheriff and asked him to mail it to the address in New York. It became incidentally mislaid, and several days afterwards the sheriff was astounded, on reverting to it, to find another complete letter in green ink, written between the lines. It showed the prisoner and the correspondent to be members of a communits [sic] society, and suggested plans of escape, threatening the sheriff and asking aid. It was discovered afterward that the miscreant had procured by some means Paris green and vinegar, which formed a liquid whose traces were at first invisible, and by the lapse of time developed these characters.

Monsieur Keff

There’s also an intriguing account courtesy of a French journalist that appeared in the Post-Star (Glens Falls, NY) on 07 Jul 1883, which Cheri Farnsworth quotes a slightly fuller version of (from the New York Sun) on pp.84-86 (but somewhat scoffs at, it has to be said):

I am positive that the so-called Henry DeBosnys was my comrade Keff. I see him still, a good-sized fellow, with long, black hair, a smooth, fat, always carefully shaved face emerging from a high white cravat, a very emphatic talker and elocutionist, especially when he recited his own verses. watching lovingly in the meantime the skillful blackening up of an old Marseillaise pipe which he seemed to have been born smoking. For five years, we met in Paris during the regular six weeks’ vacation of the provincial colleges in which he was a teacher, the university not allowing him a stay of more than one scholastic year, whether in the north, the east, the west, the south, Corsica, or even Algeria, because he always ran into debt and kept company with tipplers. I have still in my panoply the pretty pocket pistol with a damascened butt which I lent him three times to blow out what he used to call his brains, in consequence of three distinct failures in hunting rich heiresses. Keff showed me the last time I saw him the following letter:

“MR. KEFF: I’ve just found among my daughter’s papers two letters, one which is in very poor poetry, signed by you, and states that you are ready to elope with my Giuseppa on the horse of a certain Mazeppa, whom I suspect to be a licensed vendor of Bastia. The other is signed by a Mr. Peyrodal, a druggist’s clerk, now with his family at Cette. I warn you both that I give you two weeks to come and marry my daughter Giuseppa. So much the worse for the one who arrives second in the race. He is a dead man. With much respect,

BRASCATELLI D’ISTRIA,

Non-commissioned officer in the gendarmerie of Bastia.”

[…] Keff said he was going to San Domingo, and proposed to join the army there. “I am sure,” he said, “It is my true calling in this world. When young I fought like a lion near Colonel de Montagnac when we attacked Lidi-Brahim’s [sic] marabout. I even remember that I fled wonderfully quick with Major Courby de Cognord and his forty hussars, and wrote on that affair a magnificent piece of poetry.” “What nonsense, man!” [I said] “At that time you were only twelve years of age, and at Charlemagne college with me.” “You must be mistaken; I was at Lidi-Brahim, for I wrote verses about it.” I did not insist, knowing well that it was his hobby to think that he had been a witness of whatever he wrote verses about. I have not heard of him since.

Well, Farnsworth’s scoffing notwithstanding, I think you have to admit this perpetually-heiress-chasing mad-fantasist Keff does sound a great deal like our Henry Debosnys.

At the same time, I’d add that the (actual) battle of Sidi-Brahim was in September 1845, which (if Keff was, as the correspondent writes, 12 years old at the time) would make Keff’s birth year 1833.

Pierre Keff

Looking at the Keff surname, it turns out that there is a whole cluster of Keffs from Alsace-Lorraine. Because of Alsace’s close connections with Germany, a register of people from Alsace was drawn up in February and September 1872 (just after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871), which still exists and has been digitized. Of these Keffs, two in particular stand out:

- Pierre Keff, b. 12 May 1833 in Chateaurouge, who in September 1872 was living in Toulon

- Jean Keff, b. 25 July 1841 in Bouzonville, who in September 1872 was living in Toulon

Jean Keff appears in FamilySearch as having been born on 25 July 1841 in Bouzonville to Pierre Keff and Catherine Andre. Separately, FamilySearch lists the same-named couple (without ever connecting the dots) as having been the parents of:

- Madeleine Keff (born and died in January 1844 in Bouzonville)

- Elisabeth Keff (b. 11 April 1843 in Bouzonville, and who was living in Paris in 1872)

- Joseph Keff (b. 30 April 1845 in Bouzonville, baptized 1 May 1845, died 19 Jan 1846)

A Jean Keff (again, with the same parents) married a Reine Lichtenberger (daughter of Michel Lichtenberger and Reine Keser, born in 25 Sep 1836 in Oberentzen) on 18 Feb 1865 in Paris (district 19e). Though I should add that by the time of the 1872 register, Reine Keff was listed as a “femme separee” living in Paris.

As far as Pierre Keff goes: Chateau-Rouge is a commune in Moselle, right on the modern French-German border (i.e. we’re not interested in the Parisian Metro station here). And we have a marriage record for a Pierre Keff (with the same parents) marrying a Catherine Birschens (born in Pays-Bas, daughter of Jean Birschens and Marie Scharbantger) on 02 Aug 1862 in Paris (district 19e).

According to Caroline Seckel’s Ancestry tree, a Catherine Birschens was born in 2 May 1835 in Waldbillig, Echternach, Grevenmacher, Luxembourg to Jean Berchen and Anne Marie Charpentier: although she is marked down as having been married to an “unknown spouse”, it seems a solid bet that this is the same person.

As always with genealogy, it’s not 100% certain but I think it’s safe to say there would seem to be strong evidence from all this that Pierre Keff and Jean Keff were brothers, with Elisabeth Keff their sister.

Putting this together with the Parisian journalist’s recollection of Keff’s having been 12 years old in 1845, it seems reasonably likely to me that the heiress-chasing fantasist he recalled from Paris was in fact Pierre Keff (b. 12 May 1833).

What Happened to Pierre Keff?

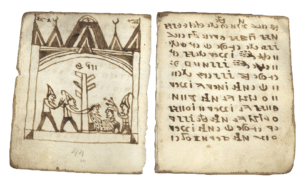

That, alas, would seem to be a very much harder question to answer. There seems to be no immigration record of any Keff going to America, or of any Keff naturalization etc. So it seemed likely to me that the best place to search would be French archival records. So I looked at Gallica, and found a hit from 5th May 1872 in Le Petit journal des tribunaux. This was a really awful slice of history, which I’ll give in French and then translate:

Jean Keff a quitté sa femme et ses enfants pour vivre en concubinage avec la veuve Bon. En allant chercher cette femme à l’atelier où elle travaillait, Jean Keff evait vu une jeune fille nommée Henriette, ouvrière du même atelier, et il conçut le projet d’abuser de cette jeune fille.

Se faisant passer pour mari et femme, Keff et la veuve Bon parvinrent à se faire confier la jeune Henriette sous prétexte d’une partie à Grenelle. Ils avaient promis que la jeune fille serait ramenée avant dix heures du soir. Cette promesse ne fut pas tenue et ils firent coucher la jeune fille dans laur logis. Pendant la nuit, eurent lieu des tentatives doieuses auxquels put heureusement résister la jeune Henriette.

C’est à l’occasion de ces faits que Jean Keff, Pierre Keff at la veuve Bon comparaissaient devant le jury sous l’accusation de tentative de voil, de complicité du même crime at d’attentat à la pudeur. L’affaire a eu lieu à huis clos.

Déclarées coupables sans circonstances atténuantes, ils ont été tous trois condamnés à la peine des travaux forcés à perpetuité.

Au sortir de l’audience, Jean keff a voulu se frapper avec un couteau qu’il était parvenu à dissimuler ; mais il a été aussitôt désarmé.

My translation (free and easy, of course you can translate it better):

Jean Keff left his wife and children and moved in with the widow of M. Bon. While going to look for this woman in the workshop where she worked, Jean Keff saw a young girl named Henriette, who worked at the same place, and conceived a plan to rape her.

Passing themselves off as husband and wife, Keff and the widow Bon managed to get the young Henriette into their trust under the pretext of a game at Grenelle. Their promise that the girl would be brought back before 10pm was not kept, and they made the young girl sleep in their home. During the night, various dubious attempts [at sexual assault] took place which fortunately the young Henriette was able to resist.

It was in respect of the above events that Jean Keff, Pierre Keff and the widow Bon appeared before the jury on charges of attempted deception, complicity and indecent assault. The case took place behind closed doors. Found guilty without extenuating circumstances, all three were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Coming out of the hearing, Jean Keff attempted to stab himself with a knife he had managed to conceal on his person; but he was immediately disarmed.

The three convicts appealed to the Supreme Court.

(There’s also a report in Le Petite Presse of 3rd May 1872 covering the same trial.)

In the appeal hearing of 30 May 1872, the court rejected the appeals of Jean Keff and Marie Ratier (la veuve Bon), but upheld Pierre Keff’s appeal because of a procedural error in his interrogation. However, the court insisted Pierre Keff should be immediately rearrested, reinterrogated (properly this time) and re-tried for the same offence.

So… What Happened Next?

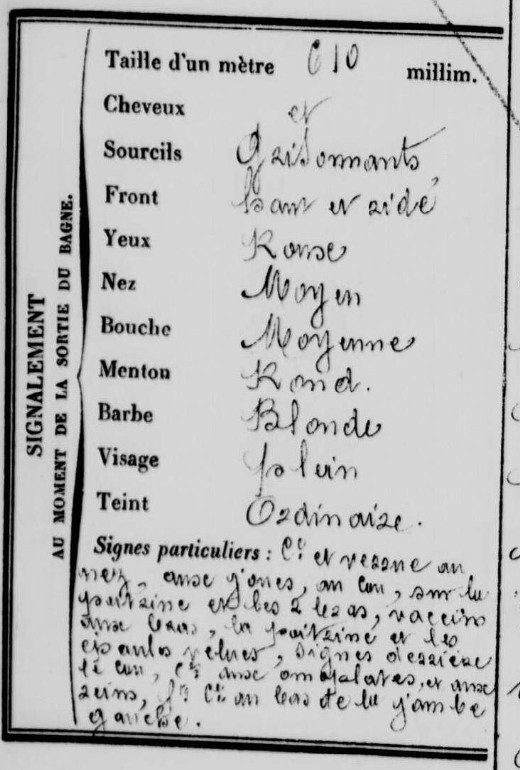

If both Jean Keff and Pierre Keff were in Toulon in September 1872, it seems likely to me that they were both in the Bagne of Toulon (1748-1873), the gigantic prison made (in-)famous by Victor Hugo in Les Misérables. So it would seem likely that Pierre Keff’s retrial happened, and that Pierre was then sent to the Bagne with his brother for a similar life imprisonment.

We know that Henry Debosnys’ body was found to be covered in (what seemed like) shocking tattoos (typical of prisons), and that he was also thought to be expert in escaping from prisons. So this would seem to be the point where the two bigger narratives might somehow overlap and merge into one, right?

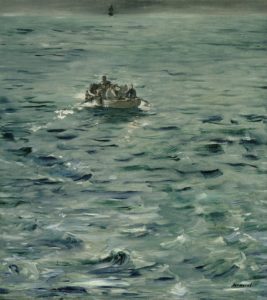

What are the odds that Pierre Keff escaped from the Bagne, and fled to America under an assumed name, leaving his – errrm – miserable life in France behind him? Actually, it turns out that this is fairly unlikely, because few people escaped Le Bagne. (If anyone has access to Docteur Raoulx’s (1929) “Le Bagne de Toulon“, a (small) roll-call of escapees is apparently on pages 17-20.)

All the same, given that it was 1873 when Le Bagne was closed, the Keff brothers were almost certainly then moved on to other prisons: so it could well be from a different prison that one (or indeed both) escaped. But I haven’t found any record of this.

Huge kudos to anyone who can find evidence that Pierre Keff escaped from prison, because despite my best efforts I’ve basically run out of runway here. 🙁

Mary Celestine

One last brief thing: because Debosnys talks of “Mrs Celestine”, I wondered whether ‘Celestine’ might have in fact been his previous wife’s surname rather than her first name. And a quick search of Ancestry revealed that in 1870 there was indeed a Mary Celestine (age 30, born in Pennsylvania) working as a teacher in Philadelphia Ward 27 District 89, and apparently living with lots of other teachers and children. Given that the lady at the top of the page seems to have a job title “Lady Superioress”, my guess is that this was a small Catholic boarding school.

So: might Mary Celestine have actually been a nun at an earlier stage in her life? After everything else I’ve found out today, that wouldn’t surprise me one little bit. Perhaps we shall see.