I’ve just found a very intriguing reference to Anthony Petti’s (1977) book “English literary hands from Chaucer to Dryden” (a copy of which which I have of course ordered, and which I hope will arrive within the next month).

It was mentioned by Isabel De la Cruz-Cabanillas and Irene Diego-Rodríguez of the University of Alcalá in their (2018) “Abbreviations in Medieval Medical Manuscripts”, downloadable via Researchgate. They rely mainly on Petti (1977) pp. 22-25 for their functional description of how abbreviation works in manuscripts: so yes, it is indeed true that I have once again blown £40+ of my book budget on four measly pages. (Possibly even just one.)

Note that they also cite:

- Hector (1958) “The Handwriting of English Documents“, pp. 28–38

- Denholm-Young (1964) “Handwriting in England and Wales” pp. 64–70

- Brown (1993) “A Guide to Western Historical Scripts from Antiquity to 1600“, p. 5

- Preston & Yeandle (1999) “English Handwriting 1400–1650. An Introductory Manual“, pp. ix–x

- Clemens & Graham (2007) “Introduction to Manuscript Studies“, pp. 89–93

Michelle Brown’s book I already have here (somewhere, *sigh*), so I’m pretty sure I’ve already seen her page 5. But the obvious reason I haven’t looked at the rest (bar Ray Clemens’ book) is that they talk specifically about English manuscripts, which is something that I’ve never particularly considered in the context of the Voynich Manuscript.

So: why might a Voynich researcher suddenly be so interested in English manuscripts?

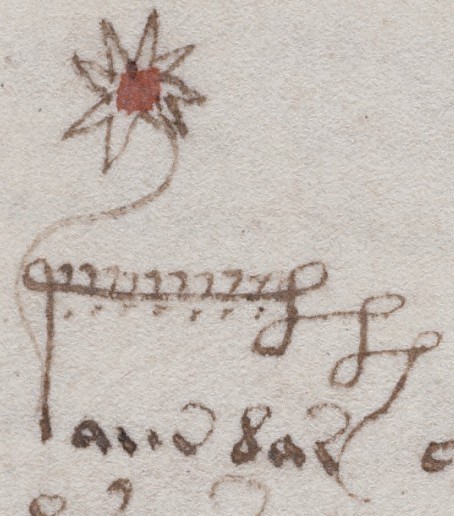

“How to deal with this pompous loop?”

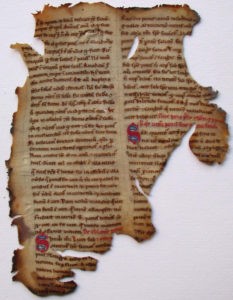

Basically, what Cruz-Cabanillas & Diego-Rodríguez are talking about is 15th century English scribal abbreviation mechanisms: but in terms of those mechanisms’ “Marvel origin stories”, these were – for the most part – Latin scribal mechanisms which English scribes had appropriated for abbreviating English.

In C-C & D-R’s section on contractions (p.170), they mention the macron-like suspension mark used (very widely) to indicate that letters have been removed (usually a nasal ‘m’ or ‘n’). However, they also describe a very specific stroke I hadn’t heard specifically mentioned before:

The usual form to mark the omission is a bar, but Petti (1977: 22) mentions an older variant, “though still in use in the late 15th century, was a crescent-shape, often with a dot below”.

That’s interesting in itself: but it’s immediately followed by something even more interesting:

When the abbreviation takes place at the end of a word, “in cursive hands there was a practice of making either the bar or the apostrophe part of the upward curve on the final stroke of a letter” (Petti 1977: 22) When the word ends in <n> this poses the problem whether the mark above the final letter is to be extended or it is just an otiose stroke. This happens very often with words containing the suffix in <-ion>, such as decoccion in Hunter 328. Here the editor must decide whether the stroke going up and backwards is a decorative flourish or should be expanded.

They continue their high-speed summary of Petti’s discussion in their section on “Curtailments and suspensions” that appears next (p.171):

Often final <n>, as it happened in the case of suffix <-ion> above, may show a bar on top of it or a kind of pompous stroke going up and backwards. It is always troublesome how to deal with this pompous loop. Alonso-Almeida (2014: 98), in the case of Present-day English gallon in Hunter 185 f. 51r, interpreted it as galoun. Nevertheless, some other editors, when the final stroke parts from the line level of letter may consider it an otiose stroke and the word would be rendered as galon instead.

Other examples of this “pompous stroke” noted by Cruz-Cabanillas & Diego-Rodríguez are:

- Harley 2378, f7r, “Saturn[e]” – see Means (1993: 246)

- Additional 12195, f187v, “mon[e]” – see Taavistainen et al (2005)

What are you thinking about here, Nick?

Plainly, the reason I’m so interested here is that Petti (via C-C & D-R) seems to be flagging exactly the kind of 15th century scribal abbreviation mechanism I’ve been searching for over the last 15 years or so, that other sources had talked about (but just not in a specific enough way to be helpful).

If you look at the glyphs that appear in the Voynich Manuscript, I’d argue that there’s something of the opportunistic jackdaw about their choice. For instance, EVA’s choice of letter-shapes notwithstanding, the EVA n on the end of the “aiin” group looks more like the v in “aiiv”: which I think matches up with the (fairly common) “aiir” group we also see to provide a visually striking “a ii r[ecto]” and “a ii v[erso]” pair.

Similarly, I’ve long believed that the “4o” pair (EVA qo) was almost certainly a pre-existing (late 14th century) letter pair appropriated by the Voynichese alphabet designer in order to solve some kind of writing/ciphering problem (because we see exactly the same 4o pair appearing in multiple cipher keys from around Northern Italy from this period.)

So: what I’m now wondering is whether the scribal loop we see at the end of “aiiv” group going upwards and backwards may well be a Voynichese appropriation of the same abbreviating pompous loop that Petti is describing.

Incidentally, the earliest examples of similar scribal ‘tics’ that I’ve seen are in some documents from Rome dating to the early 1450s that I found in a palaeographic source book at the BL. But even there I’m 90% sure that those would be characterised as “otiose loops” rather than “pompous loops”.

Where next from here?

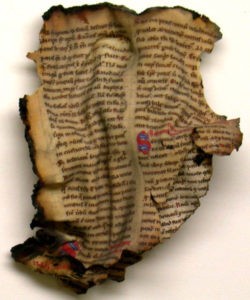

The list of manuscripts that Cruz-Cabanillas & Diego-Rodríguez specifically mention as having pompous loops are:

- Glasgow, University Library, MS Hunter 185 – early 15th century (book of recipes etc)

- Glasgow, University Library, MS Hunter 328 – late 15th century

- British Library, Harley MS 2378 – mid 15th century

- British Library, Additional MS 12195 – around 1477 (“A great part of this volume would appear to have been written by John Leke, of Northcreyke, in Norfolk, in the reign of Edward the Fourth”, saith the BL)

Unsurprisingly, the kind of things I now want to know are:

- What exactly did Petti say about this pompous loop?

- Where can I see examples of this pompous loop?

- Are there pompous loops in other languages / countries?

- Do palaeographers writing in other languages have their own names for this pompous loop?

- etc

But rather than overload this post yet further, I’ll continue this discussion in a follow-on post…