I’ve been raking over Ancestry.com, trying to take the search for the Somerton Man back to archival basics. For example:

- we have a first initial (T or J)

- we have a surname (Kean or Keane)

- we have a rough date of birth (1900, plus or minus five years)

- we know he had no tattoos / distinguishing markings

- his matrilineal DNA seems to be connected to the Baltic states

- we have practical reasons to connect him to America

- we have even better reasons to connect him to Australia, and yet…

- all efforts to find an Australian by that name seem to have failed.

The first half of the 20th century was a time of migrations: and I think the little we know about our mysterious man seems to echo that same mobility. Might we be able to catch a glimpse of him in the shipping records, that box of tricks so loved by genealogists? I went looking for Keans on ships…

John Hall Kean of Galashiels

Having previously put so much time into tracking down H. C. Reynolds on the R.M.S. Niagara, my Somerton Spidey Sense tingled when I saw a young J Kean working on the same ship roughly a year after Reynolds’ stint.

- 10 Oct 1919 Honolulu, Hawaii (from Vancouver) “cadet”, engaged 2/10/19 in Vancouver

- 28 Oct 1919 Sydney, New South Wales (from Vancouver) “cadet”, age 19, born in Scotland

- 8 Apr 1920 Honolulu, Hawaii (from Vancouver) “2nd grade”, engaged 27/2/20 in Sydney

- 26 Apr 1920 Sydney, New South Wales (from Vancouver) “2nd grade”, age 20, born in Galashiels

- 16 May 1920 Honolulu, Hawaii (from Sydney) “2nd grade steward”, engaged 30/4/20 in Sydney, able to read, age 20.

- 3 Jun 1920 Honolulu, Hawaii (from Vancouver) “2nd grade steward”, engaged 30/4/20 in Sydney, able to read, age 20.

- 21 Jun 1920 Sydney, New South Wales (from Vancouver) “2nd grade steward”, age 20, born in Galashiels

- 10 Jul 1920 Honolulu, Hawaii (from Sydney) “2nd grade steward”, engaged 24/6/20 in Sydney, age 20

These are surely all the same J. Kean, from Galashiels in Scotland.

(We also see a 21-year-old 5′ 9″ Scottish-born J. Kean arriving in California in 1921 on the S.S. Bradford. And a 5′ 5″ 160lb Scottish-born John Kean arriving in Seattle from Vancouver on 19 Dec 1922. I’m guessing these are him too,)

Knowing that, it didn’t take too long to work out that his full name was John Hall Kean, his parents were John Patrick Kean and Margaret Kean (nee Murray) (both born in Galashiels), and that he, his parents, and brothers Thomas Murray Kean and Louis Ennis Kean all emigrated from Scotland to Vancouver in 1910. (You can see them all listed in the 1911 Canada Census.) His birth date is listed there as August 1901.

We next see him working as a clerk, and getting married in 30 Jun 1923 to Vancouver-born Olympia Emily Svenciski (it’s a Polish surname). The Vancouver Daily World noted that she was the “second daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Anthony Svenciski, of this city”.

However, it’s through Olympia’s findagrave entry that we find John Hall Kean’s death, on 20 Dec 1940 at Trail (a town in British Columbia).

Oh well. 🙁

John William Kean of Hull

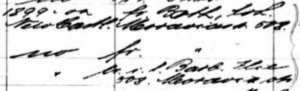

There’s a J.W.Kean who also made a number of trips:

- 07 Nov 1920 New York, age 20, on the Justin, signed on 25 Sep 1920, Newport, News (and then immediately signed back on again)

- 07 Nov 1920 New York, he is listed as John W. Kean, “sailor”, English, British, 5′ 6″, 150lb, headed off to Pernambuco (in Brazil)

- 15 Feb 1921 New York, age 20, on the Justin, discharged

- 29 Apr 1921 Sydney, New South Wales on the SS Port Melbourne from New York via Melbourne, age 20, from Hull, “sailor”

- 22 Jun 1921 Sydney, New South Wales on the SS Port Melbourne from Wellington NZ, age 20, from Hull, “sailor”

- 14 Feb 1922 New York from Brazil on the Justin, age 20, British, signed on Nov 28th 1920, NY

Familysearch helpfully suggests a John William Kean, whose birth was registered in Hull in the Jul-Aug-Sep quarter of 1901, and who did his military service in the Royal Navy from ~1918 to ~1921.

There’s also this guy from 1930, who sounds like the same person but now with American citizenship:

- 28 Nov 1930 New York on the Capulin, John W. Kean, A.B., engages on 16 Oct 1930 in Norfolk, aged 29, American race and nationality, 5′ 6″

Personally, I think John William Kean’s height is sufficient to rule him out from being the Somerton Man, but perhaps others will feel compelled to pursue him further.

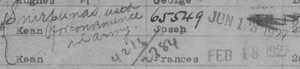

John Kean of Skerries, Dublin

The next Kean I looked at was on the Ajana in Nov 1919, an 18-year old “AB” (able-bodied seaman) arriving in Sydney from New Zealand via Melbourne.

This was probably the same John Kean of Skerries, Dublin who received his Second Mate’s Certificate of Competency on the 6th December 1922.

After a fair bit of to-ing and fro-ing looking at Ireland’s Superintendant Registration (SR) Districts, the single candidate in Ireland’s (actually extremely good) online BDM database seems to be a John Keane, born 29 August 1901 in the SR District of Balrothery.

According to the register, his father John Keane was a sailor from Skerries, and his mother was Rosanna Keane (nee McGowan). (We can also see their marriage of 02 Jun 1890 online.) The “informant” was Mary Dooley of Skerries (who was “present at the birth”).

The Irish archives have one more trick for us. On 03 Mar 1930, a John Keane (a “grocer”, aged “Adult”) of Skerries married Alice Seaver (also aged “Adult”) of Skerries: John Keane’s father John Keane was noted as being a “sea captain”. It seems very likely to me that this was the same John Keane.

But… what happened to this John Keane and Alice Keane?

Note that an Alice Mary Keane died in East Geelong on 08 Nov 1999: however, we can see her living at 46 Gheringhap St in Geelong in 1937 (“home duties”) with a John Francis Keane (“labourer”), and then again in 24 Garden St in 1942, so we can almost certainly rule her out.

So the short answer is that I have no idea just yet, sorry. 🙁

A Quick Summary

I didn’t have to look very hard to find three J. Kean[e]s who each fits the broad template of what we are looking for, insofar as their lives linked Europe with both America and Australia (albeit perhaps only briefly).

And it was nice to discover that genealogy tools – when they work well – now make it almost comically easy to trace and eliminate candidates. They all have their quirks, sure: but what would take a matter of weeks or months is now very often no more than a handful of mouse-clicks away.

However, I’m also well aware that what I picked to work with were undoubtedly the lowest-hanging fruits. Having ten or more data points to work with meant that just about everything here clicked in as you’d hope.

All the same, this has left me wondering whether it might be worthwhile to build up a list of pretty much all the J/T Kean[e]s born around 1900 (say 1895-1905), and then trace them all. Even though Ireland’s BDM database lists numerous J/T Kean[e]s, it also (once you get the hang of the SR Districts etc) gives you enough other data to rule most of them in or out very quickly.

Is that crazy? Or might it actually be achievable?