Here’s a book I’m really looking forward to reading: “The Montefeltro Conspiracy“, by Marcello Simonetta (due for hardcover release 3rd June 2008, 304 pages). Readers in Italy will get to see it earlier: Rizzoli will be publishing the Italian version first, on 26th April 2008… the 530th anniversary of the well-known Pazzi conspiracy.

And here is why I’m so excited…

Several years ago, I uncovered an apparent cryptographic link between the ‘4o’ letter pair in the Voynich Manuscript and a number of ciphers apparently constructed by Francesco Sforza’s cipher minions, both before and after his takeover of Milan. Sforza’s long-time chancellor was Cicco Simonetta: and so, I reasoned, if there was anything out there to be found, it would be sensible to start with him. However, as normal with the history of cryptography, most papers and articles on Cicco dated from the 19th century, when the subject was last in vogue. *sigh*

After a lot of trawling, the best recent book I found was “Rinascimento Segreto” (2004) by the historian Marcello Simonetta (FrancoAngeli Storia, Milan). Even though Marcello’s eruditely academic Italian was many levels beyond my lowly grasp of the language, I persisted: and my efforts were rewarded – the book’s chapters III.1 and IV.1 had everything I hoped for on Cicco.

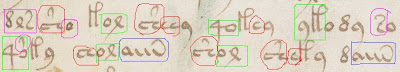

Initially, Marcello Simonetta’s interests in Cicco Simonetta seem to have been stirred up simply by their shared surname, rather than by any focus on cryptography per se: but over time this developed into something much larger. And when Marcello found a ciphered 15th century letter in the private Ubaldini archive in Urbino, he couldn’t wait to try out Cicco’s Regule (rules) for cracking unknown ciphers, to see if they actually worked. And they did!

What he found was that it was in fact a letter detailing an inside view of the Pazzi Conspiracy, a 1478 plot to kill the heads of the Medici family (Lorenzo only just managed to get away). When Marcello’s discovery was announced (around 2004), there was a bit of a media scrum: but since then he has kept his head down and written an accessible book (I hope!), and got a deal with Random House (well done for that!).

Cryptographically, the supreme irony (which I hope Marcello picks up in his book) is that we have no evidence that Cicco Simonetta’s Regule were ever used to break real ciphers in the wild – to me, it seems likeliest that the Regule were instead mainly used to keep the Sforza’s code-clerks honest, as they spent their (probably abundant) spare hours cracking each others’ ciphers. But perhaps Marcello has more to say about this in his book… we shall see! 🙂