I spent last Saturday at the National Archives in Kew, accompanied by fellow programmer Stu Rutter who is just as fascinated by the whole pigeon cipher mystery as I am. Between us we did a kind of “Extreme Programming” two-man research team thing, where every time one found something unexpected or cool or had an insight, he would call the other over to see, or we’d both go downstairs to the café and discuss where we’d got to over a sandwich or whatever (reminder to self: don’t choose the double chocolate muffin again, it wasn’t very good).

The big result is that we ended up (I’m pretty sure) working out the secret history of this dead pigeon… and we didn’t even need to break its cipher (though Stu’s still on the case, more on that below). I’ll divide the overall argument down into a series of individual steps so that any passing Army historian who wants to take me to task over any detail can do so nice and easily. 🙂

1. Percy was an Army pigeon

I was already pretty sure of this: when I looked up all the “A Smith”s in the armed forces, every single “Serjeant” [with a ‘j’] was in the British Army. But what emerged at the National Archives were two widely-distributed pigeon-related documents (one from 1941, the other from 29th Jan 1944) that made it absolutely clear what different colour pigeon-carried canisters meant:

WO 205/225 – see pages 1/2/3 (at the back of the folder)

* Red = US Forces + British Army

* Blue = US Forces + British RAF

* Blue with coloured disk = British RAF

* Blue with white patch = RAF

* Red with coloured disk = British Special Service

* Grey = British Special Service

* Green = British Special Service

* Black = British Civil Police

* Yellow = British Commercial

Hence our dead pigeon was an Army pigeon; or (to be more precise) a NURP pigeon commandeered by the British Army.

2. The signature is that of Lance Serjeant William Stout

Knowing for sure that we’re looking at an Army message helps us narrow down the list of suspects to (I’m quite certain) one and only one individual – Lance Serjeant William Stout of 253rd Field Company of the Royal Engineers (as predicted here before), whose war grave says he died on 6th June 1944, the day better known as D-Day. You’ll read far more about Stout further down…

3. The pigeon was sent from France by a French speaker

I’m 99% certain that the “lib. 1625” writing on the cipher message was short for “libéré” (released) in French, and hence it seems overwhelmingly likely to me that the pigeon was released in France. But because there were no Royal Engineers at all in France (or indeed in Holland or Belgium) between the Dunkirk Evacuation (27th May 1940 – 4th June 1940) and D-Day (6th June 1944), the pigeon can therefore only have been sent either on or before 4th June 1940, or on or after 6th June 1944.

This gives us two “bubbles” of historical possibility to consider, the first ending with Dunkirk, the second starting on D-Day. How can we possibly tell which one of these was the right one? And can we be even more specific?

4. The pigeons were not released on or before Dunkirk

We’re helped here by the two pigeons’ ring tag identifications. Pigeon “NURP.37.DK.76” was the 76th pigeon to be ringed in 1937 by the DK (probably Dorking, we think) group of NURP [National Union of Racing Pigeons] pigeon fanciers, while “NURP 40 TW 194” was the 194th pigeon to be ringed in 1940 by the TW (almost certainly Tunbridge Wells) group. Yet having now read up on war-time pigeon-breeding administrivia at the National Archives, I know that (a) pigeons don’t normally breed in Winter; (b) pairs of pigeons will typically produce up to three pairs of eggs in a year, starting in Spring; (c) a young bird aged 6-8 weeks is called a “squeaker” and needs a fair bit of training before it is ready to race; and (d) pigeon races held in the first part of the summer almost never involve pigeons born earlier that year.

Hence if pigeon “NURP 40 TW 194” flew on 5th June 1940, it would have had to have been born in the middle of Winter right at the start of 1940: and the chances of there having been 193 other birds born and ringed earlier in 1940 among a single group of lofts around (say) Tunbridge Wells are extremely close to zero. Once you look at it like that, I think that there is no real chance that this pigeon was sent back from the Dunkirk evacuation, because it would simply have been too young.

5. The pigeons were released on D-Day itself – 6th June 1944

Here, the letter and number groups in the ciphertext itself give us the clues we need. Having also read up on the multitude of Army ciphers used in WW2 at the NA, I’m 99% certain how the structure of the wrapper around the cipher was contructed. Firstly, whatever system was employed for the cipher itself, the AOAKN letter group (which appears at the start and at the end of the message) is very likely an obfuscated or enciphered key reference for the message as a whole. And if this is right, then 1525/6 must surely hold the time and day of the month the cipher was sent at. “1525” = 3.25pm, “6” = “6th June 1944″… i.e. D-Day itself. But as we will see with Lance Serjeant Stout, this is the only day he could have sent it… though not quite as simply as you might expect from his gravestone.

6. Lance Serjeant Stout was mortally wounded on D-Day, and died on 28th June 1944

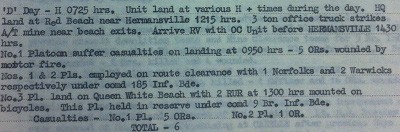

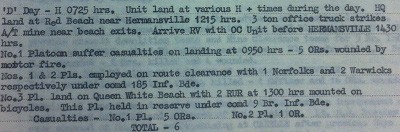

Right before the National Archives closed on Saturday, Stu & I managed to sneak a few minutes with the 1944 War Diaries for 253rd Field Company in the locked room at the back (someone else had put these diaries aside for photocopying this precise page, which made Stu and me both wonder if he or she might be a Cipher Mysteries lurker? Well, a big hello to you if that’s you!). Here’s what the entry for D-Day says:-

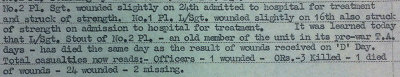

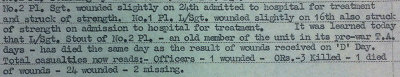

Well… not really very informative, you might think at first glance. Yet here’s where Stu Rutter really shone: having taken a photo of every page for June in these War Diaries, he then checked them all that evening and was pleasantly surprised to find an informative entry discussing Stout on the 28th June 1944:-

From this, we know for sure (a) that Stout was indeed in Normandy on D-Day; (b) that he was mortally wounded near Hermanville-sur-Mer (where he was later buried in the War Cemetery); (c) that he died of his wounds on the 28th June 1944; and that (d) he was in No. 2 Platoon. Stout was an NCO (“non-commissioned officer”, i.e. someone who had advanced through the ranks, rather than parachuted in from a public school fast-track), and at 37 was doubtless older than most of the men in in his Field Company. As my friend Ian suggested, perhaps this helped make Stout something of a father figure to many, for I think there’s definitely a warm combination of respect and fondness at play in this latter entry, quite a contrast to the consciously dry detachment evident in most of the others.

Combine what we know from this with the entry for 6th June 1944, and we can see precisely what Stout was doing on D-Day: assisting the tanks of 185th Infantry Brigade as they tried (unsuccessfully, as it turned out) to push inland to take the town of Caen by nightfall. But… what happened to 185th Inf Bde on D-Day?

7. Meet the unnamed NCO who spiked them all.

Having gone looking for a history of 185th Infantry Brigade, I found this web-page from a group of historical re-enactors who have a particular interest in that very brigade on that very day. Essentially, according to their accumulated history of events on D-Day, what happened is that around about 2pm, 185th Infantry Brigade’s advance was being held up by a group of Germans shooting at it from the cover of some woods. It needed help to make progress against these very well dug-in defences. The web-page continues:-

Eventually a Pole was captured who knew the way through the wire at the back of the battery. The gunners fled into the woods, harried for some hundreds of yards by the Company. The guns were then blown up by an unnamed N.C.O. of the Divisional R.E.s, who, though badly wounded, succeeded in “spiking” them all.

Who was that “unnamed NCO”? Unless anyone can demonstrate otherwise, I think it’s not being overly romantic to believe that this man was Lance Serjeant William Stout – he was an experienced NCO in the Royal Engineers, he was in No. 2 Platoon assisting 185th Infantry Brigade outside their temporary base in Hermanville, he was badly wounded, yet he did the right thing in obviously difficult and trying circumstances. If anyone can be said to be “Stout-hearted”, it was surely him.

8. What kind of cipher did he use?

According to diagrams in the documents we found in WO 193/211, Royal Engineers were only supposed to use low grade ciphers in the field. But which?

One likely candidate is the Double Transposition Cipher (introduced 5th Nov 1943 in document 32/Tels/943). Yet one problem with Double Transposition as a candidate here is that encipherers were required to finish up the message with a pure number group containing the number of letters in the cryptogram followed by a forward slash and the day of the month (i.e. “179/12”), which plainly wasn’t what was used here. For a number of reasons like this, Double Transposition was thought to be “difficult and slow to operate”… possible but not ideal for use in the field.

The other major possibility here is the low grade “Syllabic Cipher”, a system I unfortunately failed to find described in any of the National Archives documents I looked through (which, let’s face it, do tend to be more administrative than operational). However, I do know that this cipher used a book marked “BX 724”, while the Royal Engineers had their own specific version marked “BX 724/RE”: these presumably comprised tables of syllables, which were then offset / obfuscated using a key from a Daily Key Allocation List. Stu has already gone off looking for anything like this and/or any other information on the Army’s Syllabic Cipher, but please email me or leave a comment here if you know where in the archives to find more information on these!

9. After all that… what did Stout’s pigeon message say?

It’s 3pm in the afternoon of D-Day. Lance Serjeant William Stout has just destroyed the arms of a German battery to help clear the way for 185th Inf Brde to move on towards Caen. He’s wounded. He wants to get a message back to his field company, but radio traffic has to be kept to a minimum. My best guess? 185th Infantry Brigade have brought with them some pigeons and a bilingual (but English-born) translator who is also a pigeon fancier. Despite his pain, Stout writes down his message and he (or someone else) rapidly enciphers it using a Syllabic Cipher (or possibly a Double Transposition Cipher, though I somewhat doubt it). This contains 27 groups of five letters, i.e. up to 135 plaintext letters – roughly 25 to 30 words. So, perhaps we can guess it says something along the lines of… SPIKED ARMS OF GERMAN BATTERY OUTSIDE HERMANVILLE 185 INF BDE NOW MOVING FORWARD AM BADLY WOUNDED TELL WIFE AND CHILDREN ETC. He starts copying the enciphered message onto the form at 15:22 (British Time), finishes copying it at 15:25, passes it off to the bilingual pigeon fancier, who signs them off at 16:25 French Time, places them in red Army canisters, attaches them to a pair of commandeered pigeons and then releases them.

However, it’s worth remembering that of the 16,000+ pigeons released on the Continent by SOE, I believe that only around 1,250 returned safely. So perhaps unsurprisingly, it could well be that one of these two pigeons failed to make it back at all; while the other did make the 136 or so miles back to Bletchingley, which I suspect will turn out to be remarkably close to its home loft: flying at 45mph or so, the bird likely took about three hours. Yet as it briefly rested there on top of a roof at about 6.30pm at the end of what had been a thankfully clear day (or else D-Day would have been an unmitigated disaster!), could it be that someone in the house below lit an evening fire in a hearth, unknowingly sucking the poor pigeon to its death down in the chimney?

* * * * * * * * *

All of which makes a great dinner-table story, with the added bonus that a fair proportion of it is certainly true… but will this turn out to be the whole story? Perhaps we’ll find out before too long… fingers crossed that we do! 🙂

Incidentally, has anyone tried to trace Lance Serjeant William Stout’s son (also William Stout) or daughter (Urula Stout)? Perhaps they already know even more about this than we do… I for one hope they do!