Having got hold of a WW2 Slidex manual, I’m starting to see what a travesty of a coding system it was – and how a smart German decrypter could (with a bit of practice) decipher it almost in real time.

But Slidex was never intended as a highly secure coding system: it was only supposed to be a convenient way for people to discuss very short-term matters mostly in the clear over the radio or telephone, encoding any individual items or details that should not be overheard by the enemy. In fact because of its obvious lack of security, I don’t believe it was even classified as a “low grade” cipher.

Yet for a whole host of pragmatic reasons, it seems that Slidex was chosen to be used on D-Day for all non-machine cipher traffic. So if the pigeon cipher is in Slidex, can we crack it?

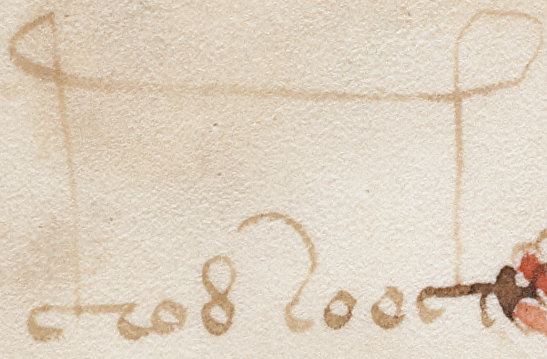

The first big problem we face is that “Slidex as described in the manual” and “Slidex as used in the field” seem to be quite different beasts. For example, though both employ a 12 x 17 (= 204-cell) table, manual-Slidex used a 12 letter horizontal key at the top, whereas field-Slidex (as evidenced by various pictures) seems to have used a pair of characters per key horizontal cursor cell, hence a 24 letter horizontal key. Similarly for the vertical key, manual-Slidex used only 17 characters whereas field-Slidex seems to have used all 26 alphabetic characters. So unless someone kindly comes forward and tells us how Slidex was actually used circa D-Day, we’re kind of stuck in a no-man’s land between manual-Slidex and field-Slidex, uselessly trying to guess what’s inside the Baggins’s nasty little pocket, yessss.

The second big problem is that unless something rather miraculous emerges from GCHQ’s archives, it now seems fairly unlikely we will ever get retrospective access to the daily keys used. Key pairs were tightly controlled and never used for more than 24 hours at a time (keys were normally changed over at midnight each day).

And yet… Slidex is designed to be quick and easy to use, with exactly the same code table and key pair used by both encoder and decoder. And in practice, all the symmetries and shortcuts that yield all that convenience also compromise the security to the point of uselessness.

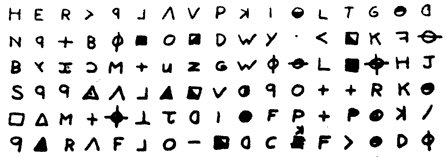

For example, every 12-column-wide code table is arranged into three groups of four columns: and in each one I’ve seen, each group includes all 26 letters of the alphabet in alphabetic order, as well as a third of the numbers from 00 to 99, and a few SWITCH ON and SWITCH OFF cells. Moreover, in the code half of the cells, all the words are arranged in alphabetic order from top to bottom.

For example, the first four columns of the Royal Engineers Series A code table “No. 1” proceed like this:-

[?] 08 N T

0/? G 16 24

OFF 09 O 25

00 H P U

A I 17 26

01 1/? 18 ON

B J 19 V

C 10 2 27

02 11 Q W

D K 20 X

03 12 R 28

E 13 S 29

04 L ON 3

05 14 21 Y

06 M 22 Z

F ON T 30

07 15 23 31

(Original picture from Jerry Proc’s Slidex page, second image from bottom. Note there’s also a photo of an Op/Sigs code table there that closely follows the same kind of layout pattern).

Moreover, the German cryptologists interviewed by TICOM after the war noted that before September 1944, most people using Slidex tended to use the leftmost group of columns almost exclusively, which compromised yet further what was already a poor system. And the widespread habit of using Slidex for entire messages made the daily keys easier to get to rather than harder. What a mess!

And so if our mysterious dead pigeon message is in Slidex, all those flaws and poor enciphering practices might give us enough to decrypt it without a daily key, or even without a code table at all! After all, if the Germans could do it (albeit usually with more depth to work with), surely so can we?

Looking again at the bigram, if we precede each bigram with the number of times the first half of the pair occurs, I suspect we can predict fairly reliably which part of the message is in code and which part is in cipher:-

6HV 3PK 3DF 3NF 2JW 2YI 3DD 2CR

4QX

... 1SR 3DJ 6HF 3PG 1OV 3FN 4MI

4AP 1XP 4AB 1UZ 1WY 2YN 3PC

... ... ... ... ... ... ... 4MP

3NW 6HJ 4RZ 6HN 2LX 4KG 4ME 4MK

4KO 3NO 2IB 4AK 1EE 4QU 4AO 4TA

4RB 4QR 6HD 2JO 3FM 4TP 1ZE 6HL

4KX 3GH 4RG 3GH 4TJ 4RZ 2CQ 3FN

4KT 4QK 2LD 4TS 3GQ 2IR

Because so many single instance “1nn” pairs are clustered in the middle section (“1SR … 3PC”), I’m pretty sure that this is in code, and the last part (“4MP … 2IR”) is in cipher. The first part I’m unsure about.

If we now concentrate purely on the final section and look at the frequency counts and patterns there, plenty of other interesting things jump out:-

... ... ... ... ... ... ... 3MP

2NW 4HJ 4RZ 4HN 2LX 4KG 3ME 3MK

4KO 2NO 2IB 2AK 1EE 3QU 2AO 4TA

4RB 3QR 4HD 1JO 2FM 4TP 1ZE 4HL

4KX 3GH 4RG 3GH 4TJ 4RZ 2CQ 2FN

4KT 3QK 2LD 4TS 3GQ 2IR

From the way they cluster, I think that M and Q probably refer to the same column: and from the few single-instance “1nn” bigrams in there, I suspect that “EE” and “ZE” probably both encipher “E” (while “JO” could well encipher “T”).

What’s interesting is that it seems likely that the four columns encipher letters in alphabetic order: so (say) A-F, G-M, N-T, and T-Z in the case of the Royal Engineers code table #1 (there are a couple of extra E and T characters inserted around the table). It may be that this is enough for someone to try to solve this directly without any other information!