I don’t often cover the Phaistos Disk here, simply because it’s almost certainly more of a linguistic mystery than a cipher mystery as such. However, I was particularly taken by some aspects of the analysis offered by Keith & Kevin Massey, so it seemed well worth discussing here.

Incidentally, despite their complementary-yet-competing philological interests, the twins didn’t start their Phaistos Disk adventure together. But, as they put it, “for Kevin to collaborate with his brother Keith was finally inevitable, like dancing with your mad aunt at a wedding reception.”

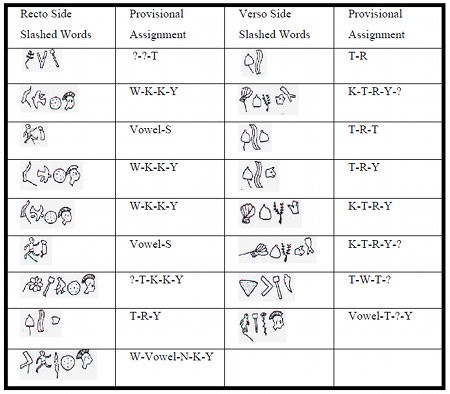

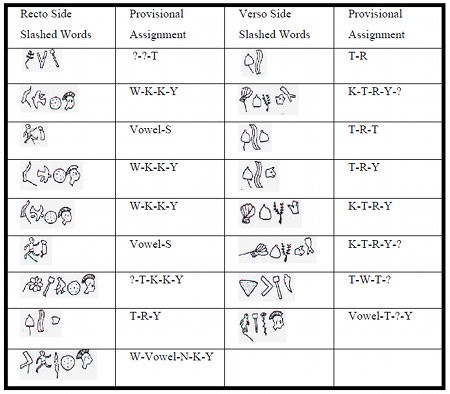

Their Chapters 1-4 summarize a whole load of Phaistos research, while trying to argue for a link between various early European scripts (Cypriotic, Linear B, etc). Their Chapter 5 (pp.48-56) argues for a left-to-right reading of the Phaistos Disk (but not quite as convincingly as they hope, I think). But after all that, their Chapter 6 discards pretty much all their preceding linguistic analysis and instead proposes the hypothesis that Phaistos Disk words with slashes are actually numbers. And that’s essentially where they finish.

Now, for all the twins’ obvious linguistic smarts, I have to say I just don’t buy into this – at least, not in the way it’s currently presented. And here’s my argument why:

(1) The way that the signs are physically imprinted / stamped into the soft unfired surface of the disk is clearly systematic (i.e. it’s a consciously prepared set of shapes, not one that’s being improvised on a shape-by-shape basis), and the choice of those shapes forms part of the same system.

(2) Furthermore, the whole disk had to be fired once and once only. Hence without much doubt the imprints on both sides had to have been made at the same time using the same basic system.

(3) Regardless of whatever direction you believe it was written in, there are substantial word differences between the two sides. Many words repeat on the same side (in fact, there’s even a three-word pattern that repeats on Side A), yet only a single measly three-imprint word repeats between sides.

(4) There is an imbalance between the shapes on the two sides. The most obvious difference is the frequency of the plumed head imprint: 14 instances on Side A but only 5 instances on Side B. Yet there are plenty of others, such as the beehive (once on Side A but five times on Side B). Indeed, the most visually striking difference is the twelve { PLUMED_HEAD + SHIELD } pairs on Side A compared to the single pair on Side B.

These are the basic observations I personally work from, and the problem is that I just don’t see how these square with the number system suggested by the Masseys. Whatever the actual significance of the slashes, it doesn’t seem to me to coincide with any obvious difference in the language as used (because the PLUMED_HEAD + SHIELD pairs occur just about as often in slashed words as in unslashed ones): and (longhand) numbers are almost always a notably differently-structured part of any language.

For me, the big issue is that Side A is significantly more structured and repetitive than Side B. Also, its word lengths have much greater variance (i.e. Side A has both longer and shorter words than are found on Side B), and they use a different mix of shapes. Yet slashed words occur just as often on both sides. I just don’t get it, me.

I suspect that Side A and Side B use different kinds of language (ritual, performative, poetic, pragmatic, whatever) to assist very different functions: and probably courtly functions at that. But seeing it as a homogeneous number container for (say) Cretan tax accounting seems far too mundane. Bean counters never touched this artefact, no they didn’t! 🙂