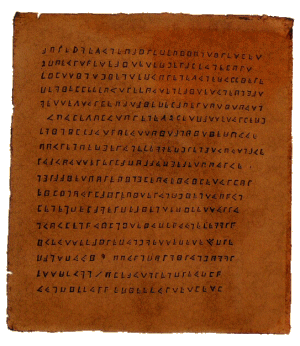

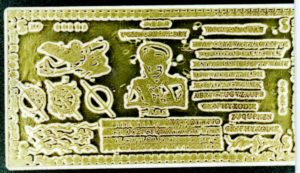

Over the last few days, I’ve been looking again at the cryptogram widely claimed to have been composed by the pirate Olivier “La Buse” Levasseur that I first properly described here back in 2013: and really, I have to say that I don’t believe a word of the supposed hidden-pirate-treasure back-story.

I’ll explain…

A Pigpen Cipher

The mysterious text is, without any real doubt, a cryptogram formed using the exact pigpen cipher layout suggested by Charles de la Roncière in 1934. But there is also, I think, strong evidence that the plaintext was already enigmatic and/or hard to read even before it was ever enciphered.

For example, one very early section of the cryptogram is in almost perfect French:

* Lines 3-4: prenez une cullière de miel

Here, “cullière” looks overwhelmingly as though it ought to instead be “cuillère” (spoon), i.e. “take a spoonful of honey”. What this suggests to me is that the person originally encrypting this text found it hard to tell the difference between ‘i’ and ‘l’ in the original (plaintext) handwriting he/she was working from. What’s more, this sounds – however disappointingly prosaic it may be to some people – a lot like a recipe of some sort. And furthermore, it is tempting to surmise from this that the encipherer was unable to read French, and was just reading and processing the letters exactly as they seemed to him/her.

All of which is rather odd: but perhaps the encipherer had inherited or acquired the plaintext and believed that it contained directions to a French pirate’s treasure (albeit one written in a language he/she couldn’t read), and so thought it more prudent to encipher it than leave it lying around en clair. This is just my speculation, of course: but all the same, there’s a whole heap of details here that doesn’t properly make sense just as it is, so there has to be some explanation for the confusing stuff that we can see.

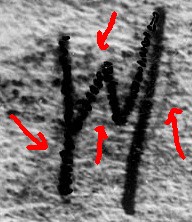

There is evidence too that the cryptogram that we have was also copied from an earlier version of the same cryptogram, specifically because of the variability of the pigpen dots. For example:

* Line 8: povr en pecger une femme [dhrengt vous n ave]

Here, if you swap pigpen dots for the first ‘v’, ‘n’, and ‘g’ you get –

* Line 8: pour empecher une femme [dhrengt vous n ave] — i.e. “to prevent a woman…”

Even with what snatches of mangled French we can (mostly) read, it seems highly unlikely to me that this will turn out to contain anything so obnoxiously capitalist as clues to hidden treasure.

A French Love Spell?

In fact, to my eyes the most convincing scenario so far is that what we are looking at here is a French love spell involving honey.

Because spells were almost always copied rather than devised, I therefore think the most practical way to untangle this whole cipher mystery would therefore be to look at as many (preferably pre-1800) French spells as possible, and see if we can discern unusual patterns there that are reflected in the text here. And any mention of honey, too. 🙂

So I took a quick look on the web, and quickly found The Passion Spells of France (2nd Edition) (though note that your $6.99 only buys you 24 pages). This includes a French spell involving placing honey in the middle of a pentacle (the “Midnight Secrets” ritual, page 15), but sadly the spells only appear in English translation and there are no notes as to the original French sources for any of them. 🙁

Note that the book also includes a “Dove Love” ritual (p.8) involving the feather of a dove: which might possibly begin to explain the otherwise generally mystifying inclusion of the “une paire de pijon[s]” [t -> s] on the first line of the cryptogram. (Incidentally, pigeons less than a month old are known as ‘squabs’ and have historically been considered a great delicacy.)

I also found a book often mentioned called “La Poule Noir” (The Black Pullet) by “A.J.S.D.R.L.G.F.” (all bar one of whose initials lie on the middle row of a QWERTY keyboard, for all you trivia fans). This seems to be included in a 1900 book by Legran Alexandre called “Les Vrai Secrets de la Magie Noire” (downloadable here), but please say if anyone finds a proper download (note that there are a whole of sign-up-for-this-service-and-get-this-ebook-free scam download pages that contain it).

A few of the recipes / rituals listed there do include honey, such as one for making newborn babies intelligent, and also one involving the left leg of a tortoiseshell cat. The love ritual involves taking a lock of someone’s hair, burning it, and spreading the ashes on their bedframe mixed in with honey. (If it brings people together, who am I to raise an eyebrow? It’s no worse than online dating, 17th century style.)

I don’t know. There must be a huge literature on French love spells somewhere out there (dissertations and books), but I’m far from tuned into that whole channel just yet. If anyone finds a better starting point into it, please say! Perhaps we’ll then start to make some genuine progress with this, rather than wasting time and effort wishing for buried treasure. 😐